‘While the media regularly lambaste students for poor attendance or requesting trigger warnings, I understand where zeds are coming from’

As an elder millennial, I sympathise with my Generation Z students. It was only very recently that the media stopped haranguing millennials for being self-indulgent consumerist snowflakes, in favour of…well, haranguing zeds for being self-indulgent consumerist snowflakes.

According to research, however, Generation Z are even worse off than their millennial counterparts. A study earlier this year reported that depressive symptoms are two-thirds higher in zeds than in millennials, and the former are also more likely to self-harm. Zeds are also more likely to be critical of themselves and others, scoring higher on perfectionism tests than previous generations.

How do we teach students who are, as The Economist recently put it, “stressed, depressed and exam-obsessed”? Perhaps part of the solution lies in hiring more millennial academics, who may be up to two decades older than their students but who share many of the same anxieties.

A lot of the press attention on Generation Z and millennial mental health has focused on the impact of social media and its encouragement of negative body image and relentless self-scrutiny, but many of our concerns are more practical. My generation was the first in the UK to pay tuition fees, while my students have seen their fees hit £9,250 a year. I am still paying back my undergraduate maintenance loan nearly a decade post-PhD, but, with the cost of student accommodation having risen by 23 per cent in the past six years, it is likely to take my students much longer still to repay their mounting debts. Especially since, while official unemployment statistics show a record low, a rise in zero-hour contracts and gig work, as well as the increased cost of living, mean that 4 million working Britons live in poverty.

Like many other millennial academics, I have experienced the sharp end of these bleak statistics, having been among the 53 per cent of academics in the UK on fixed-term contracts. Many of us have been guiding students towards graduation and life beyond university while feverishly job-searching ourselves. While the media regularly publish pieces lambasting students for poor attendance or sneering at them for requesting trigger warnings, I understand where zeds are coming from.

Life is stressful, and in striving to make my classroom a safe space for my students, focused on their needs rather than on my ego, I am not attempting to shield them from uncomfortable truths, or even to set aside their very understandable worries. Instead, I hope to equip them to deal with their problems outside class as well as inside it.

A good example is the research and employability skills module that I will be teaching this autumn. Is it as much fun to teach as my Medieval World course? Probably not, but it aims to equip history students to leverage their skills – writing essays, giving presentations, teamwork – to both prepare for their dissertations and think about the job market. Of course, universities have careers services that provide a lot of this type of training, but integrating it into the degree programme helps students see why the academic work they are doing is directly relevant to their future careers.

Running courses like this alongside modules that emphasise the historical importance of minorities – women, LGBT people, BME communities, the working class – underlines for marginalised undergraduates not only that history was made by people like them, but also that they can make history, too – both as students and in their lives after university.

Rachel Moss is a lecturer in history at the University of Northampton.

‘Australian university administrators have created a generation just as fragile as America’s brittle Trumpophobes’

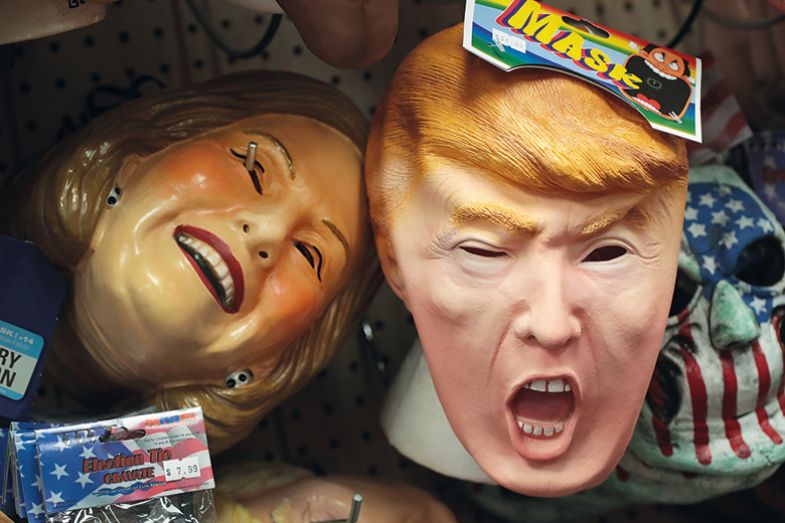

Snowflakes, safe spaces, cultural appropriation, risk aversion: we all know the drill. After Donald Trump won the 2016 US presidential election, Northwestern University organised “healing spaces” for students “wounded” by the election results. The University of Massachusetts offered grief counselling.

Meanwhile, at tiny Bowdoin College in Maine, famed for its activist student government (and superior SAT scores), a tequila-themed birthday party featuring (gasp!) mini-sombreros sparked a university investigation. And don’t even ask about Halloween. This 31 October, many British universities will surely be offering special Brexit counselling, but American university administrators habitually go on high alert at that time of year over culturally insensitive Halloween costumes.

Making fun of campus snowflakes is either deeply insensitive or good sport, depending on your point of view, but no one can deny that it has all gotten a bit dreary and repetitive. Everyone seems to have forgotten the most politically incorrect fact of all: that university students are, for the most part, kids. Young adults. Growing up. Finding their place in the world – or whatever you want to call it. Of course, there are many mature students who defy that stereotype, but they’re rarely the ones who feature in snowflake stories. They tend to be more career-focused, as well as more...well, mature.

As a Generation Xer who has made a career of teaching Generation Y and now Generation Z, I have never had any problems with political sensitivities in the classroom. I’ve pushed contrarian positions on controversial issues like climate change, gay marriage and immigration, with precious little pushback. In my experience, it’s hard to get students to talk at all, but if there has ever been a time when it was easy to engage them in class discussions, it was a long time ago. The educational philosopher John Dewey devoted most of his 1916 classic Democracy and Education to the challenge of fostering student participation.

But my quiet snowflakes are snowflakes all the same. They are literally disabled by the everyday anxieties of university life. Nearly 20 per cent of Australian students are medically classified as “disabled”, nearly all of them with a diagnosis of anxiety. That takes their reticence out of my hands as a teacher and places them under the protection of university disability administrators. They are relieved of the responsibility to participate in class and granted extra time on tests and homework. Through an excess of compassion, Australian university administrators have created a generation just as fragile as America’s brittle Trumpophobes.

Both in Australia and abroad, it was the Baby Boomers who first parlayed ordinary student insecurities into existential student fears. Now those same Boomers fall into the prime senior administrator range of 55-73 years old. Trump-wounded Northwestern is led by the economist and Baby Boomer Morton Schapiro. The grief-counselling president of UMass is the politician and Baby Boomer Marty Meehan. Leading the sombrero police at Bowdoin is the banker and Baby Boomer Clayton Rose. Whatever personal ethics these senior administrators bring to their jobs, they all grew up as part of the world’s most famously self-indulgent generation.

Now that the Baby Boomers are running the show, they seem intent on giving students all the disadvantages they wish they had had themselves. Young people have always been more sensitive and more self-concerned than the rest of us. That’s as it should be: it’s all part of growing up. But those of us who have a duty of care to the young have a responsibility to look out for their best interests, and, just like parents, to put their needs ahead of their desires. Of course students want to be coddled. Who doesn’t? But universities should always be carefully weighing the relative merits of grief counselling versus tough love.

Baby Boomers have never wanted to play the bad cop. But by always playing the good cop, to both their students and themselves, they have created a Baby Boomlet generation of self-indulgent youth. My students don’t have to be snowflakes. But, like kids everywhere, if you give them an inch, they’ll take a mile. These days, they all know that they can always go over my head and appeal to administrators, who will give them their mile. Is it any surprise that they do?

Salvatore Babones is an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney and the author of The New Authoritarianism: Trump, Populism, and the Tyranny of Experts.

‘The point of being “engaging” and “accessible” isn’t to be likeable or to dumb down: it’s about creating an inclusive and supportive environment’

I started teaching only in 2012, so I am not qualified to comment on how different Generation Z students are from previous generations. But I do know that they respond well to my approach.

This past academic year, I won two student-led teaching awards. I won the Bristol students' award for outstanding educator in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Law, and I was selected for the Best of Bristol lecture series, which showcases the best of the University of Bristol's lecturers.

Of course, there are those who claim that these kinds of awards are meaningless, because students don’t know what “good” teaching is. I myself am wary of measures of teaching excellence, such as the UK’s National Student Survey. Nevertheless, I think it is worth reflecting on what students have noticed about my teaching and what this might reveal about the current generation and their needs.

Feedback, both informal and formal, indicates that they find my style engaging and accessible. They have told me that this not only raises their confidence but also allows them to develop analytical skills that they have not gained in other units. For example, I have been told that I give “everyone an opportunity to engage” and that I remove “the intimidating element of speaking in seminars”. Another student said that I “broke down scholars’ ideas very clearly, which allowed for open critical debate and discussion, where I learned how to form stronger arguments”.

For those sceptical about student feedback and its inevitable biases, it may be of interest that an academic made similar comments when observing one of my first-year lectures: “Students were given numerous opportunities to understand, learn and apply the theory. The lecture was a supportive space and students were encouraged to share their views.” He also noted that “I have never seen a lecture this engaging. Not a single student was distracted.”

I try to create an open environment for critical engagement. My lectures are structured to include student input (for example, through live surveys), and I aim to make students feel knowledgeable, empowered and inspired to learn more when they leave the lecture theatre. My seminars have a relaxed atmosphere, in which students feel able to speak their minds but are also pushed to explore ideas critically and analytically. This usually results in animated and in-depth discussions that are enjoyable for the students and for me.

As an example, when teaching a complex moral theory like climate justice, I have students work through thought experiments via which they can “try out” analytical models for themselves. In one such exercise, I set out a few different cases of countries that have emitted x amount of carbon in the past and now have a GDP of y, and I get the students to think through which country is most responsible for responding to climate change.

This allows them to explore the idea that “the polluter pays” versus the view that “ability to pay” is the key factor in a relaxed way, using their knowledge from the reading but not being pressed on particular passages or definitions. I find that this kind of exercise spurs on critical debates much more readily than having students sum up arguments made by scholars or discussing ethical principles in the abstract.

This generation evidently want to be treated with respect and to be given the space to flourish intellectually. In this sense, the point of being “engaging” and “accessible” isn’t to be likeable or to dumb down content. Instead, it’s about creating an inclusive and supportive environment, where students are treated like intellectuals-in-training, who have something worthwhile to say. Such an environment allows students to explore academic concepts without feeling that they don’t have the skills or background knowledge to excel.

It shouldn’t be a shock that students appreciate this kind of learning experience. I also excel when I feel supported, confident in my abilities and excited about the subject at hand. As for my students, I have found that the environment I create encourages deeper learning, passion for the subject, exciting seminar discussions and excellent academic analysis in essays.

Alix Dietzel is a lecturer in global ethics at the University of Bristol.

‘Generation Z does not demand much of universities that we should not already be demanding of ourselves’

Much has been made of the generational forces that are reshaping the academy. First came millennials, a generation seemingly intent on shaping the world in its image. Millennials were not so willing to accept things the way they were, and demanded a much greater engagement with broader questions of justice and fairness at every level of society, foregrounding the university’s engagement with these issues.

And now comes Generation Z, born between 1995 and 2015 and currently the bulk of students on undergraduate campuses and, increasingly, in graduate school. Generation Z – or, at least, the highly educated, university-bound portion of the generation – has come of age expecting social justice to inflect what we do and how we speak, comfortable in a world of fluid gender norms, and deeply suspicious of capitalist motives.

By cultural stereotype, Generation Z is profoundly sensitive to perceived slights, zealously protective of individual identities, and suspicious of efforts to adopt purportedly balanced perspectives on social issues that should have been long settled. It is also the first generation of digital natives, a group effortlessly comfortable swimming in a digital sea.

Does any of this change what we teach and how we teach? Does it represent more of a generational shift than we have seen in previous decades? The answer, I suggest, is both yes and no.

Generation Z’s involvement in identity-based meaning requires a rethinking of how we talk about identities and how our previously held assumptions about them have influenced how and what we teach. Are we organising student gatherings at times and on days that privilege those who do not have other obligations, for instance? And does the inclusion of a particular book on a syllabus truly represent the best work in the area – or are we choosing it because the author shares our worldview bias?

These questions are discomfiting and inconvenient. It is, frankly, easier to just choose books unthinkingly and to schedule meetings and organise physical layout without worrying about implicit bias. Similarly, the appetite for all teaching materials to be digitally available adds a workload demand that we did not have before. It is easier to offer residential-only classes than to have to juggle residential and digital schedules, offering courses in multiple modalities.

In other ways, however, Generation Z’s expectations do not represent a discontinuity from the past, so much as an evolution – and precisely the type of evolution universities should be comfortable with. Identity-based discussions are a natural extension of the previous generation’s concern with surfacing issues of social justice that had long lain dormant. An awareness of the biases that inform our scholarship and our teaching is an extension of the critical thinking that has always been the hallmark of the academic enterprise. And digital modalities of education are just the next step on the road from chalk boards to transparencies to PowerPoint.

Seen this way, Generation Z does not demand much of universities that we should not already be demanding of ourselves: that honest and critical scholarship infuses a style of teaching that is as effective as all the tools at our disposal can make it.

Moreover, it seems to me that the shifting expectations brought to bear by Generation Z are a positive. Seen in the right light, they are a reminder of what a privilege it is to work in universities, where one has the good fortune to have shibboleths challenged on a regular basis, towards the end of thinking more clearly and creating an even better next generation. If our students in Generation Z are pushing us in this direction, we owe them all a debt of gratitude.

Sandro Galea is professor and dean at the Boston University School of Public Health. His latest book is Well: What we need to talk about when we talk about health.

‘My conclusion is that the best way to help students is simply to be there for them’

Are university students more coddled and spoiled than ever? To listen to the greybeards, you would certainly conclude that they are. But, in my experience, things are a little more complicated.

For starters, it is always hard to know how objective we are being when we judge the current generation of students. They remain, for the most part, in the 18- to 22-year-old age bracket, while every year puts more distance between us and that demographic. If we feel that students are getting more irritating, perhaps we are just experiencing the other side of the shifting intergenerational perspective that led Mark Twain to remark: “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much he had learned in seven years.”

The classroom teaching experience has certainly changed a lot since I began lecturing in 1994, but that is due to the technology (though, even now, not all lecturers are willing or able to use it). In terms of actual learning, I don’t see any real change. Students do the same things they have always done: read, listen, debate, question and write.

Still, in the UK, at least, their demands appear ever more detailed and persistent. Take feedback. Students want more of it, are unhappy with what they get, and seem to want to know – as if they’re baking a cake – exactly what steps they need to take to get a great result. When I was head of the department of politics and international relations at the University of Edinburgh, we worked hard to provide better guidance. I wrote blogs on the how and why of feedback and we met, with and without students, to try to improve its design. We tried to emulate best practice from elsewhere. Yet, each year, we sunk further in the feedback rankings.

The other thing that seems to have changed in the UK is the number of students citing special circumstances. Of course lecturers want them to be healthy, but it can be frustrating to deal with all their emotional, mental and physical conditions given the heavy administrative load that it implies.

Are they just trying to game the system? There is certainly a lot more at stake for them than there used to be. They graduate with huge debt into a tough job market, where they compete with ever-higher numbers of graduates. And that massification also directly affects the student experience. At Edinburgh, I lectured 350 students at a time, and their tutorials were taken by PhD students; they had little contact with lecturers until their honours years. As our programmes got bigger, our teaching evaluations also suffered.

So if student behaviour has changed, who is to blame? A useful comparison is offered by my recent experience of teaching Mexican students. I now work at a prestigious social sciences and humanities institute in Mexico City, whose students are on a par with those of Russell Group institutions. The big difference is the contact time they receive. For every course I teach, I’m in the classroom with my students for four hours a week, 16 weeks a semester. No PhD students do my teaching.

My conclusion is that the best way to help students is simply to be there for them. Whatever else we do, we’re responsible for their development. This requires time – as well as sensitivity, compassion and patience.

My Mexican students rarely complain that their feedback is unclear. Some claim special circumstances, but much fewer than in the UK. Perhaps they are simply a generation behind the UK. Perhaps they are culturally more reluctant to question authority. Or maybe they’re just happy.

Mark Aspinwall is a research professor in the Division of International Studies at the Centre for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE), Mexico City, and honorary professorial fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

‘Instead of reflexively decrying that students don’t read, we need to modify our notion of what constitutes reading’

We’ve heard that Generation Z students are emotionally fragile, have a disproportionate sense of entitlement and require indulgent teaching practices, but dismissing this as a generational malaise is far too glib. Greater proportions of Americans are going to college than ever before, and that means that the system contains large numbers of first-generation students who often lack the secure backgrounds of traditional undergraduates. That inevitably has big implications for the kinds of environments and teaching that students expect and appreciate.

My experience of working for three years with a diverse, mostly first-generation but predominantly middle-class set of students at the University of Houston suggests that low grades cannot be attributed to partying, gaming or procrastination. Rather, far too often, an unexpected non-academic issue sets a corrosive cycle in motion, preventing the students from coming to class or completing assignments. This results in their failing or dropping the class, and frequently leaving college without a degree – but with significant debt. These students repeatedly blame themselves, without acknowledging the consequences of interlocking systems of oppression.

Part-time jobs, family obligations, mental health issues and social media all have gravely isolating effects on these students. Income disparities engender an almost pathological form of self-reliance. Instead of reflexively decrying that students don’t read, we need to modify our notion of what constitutes reading to account for the self-improvement books, podcasts and productivity sub-reddits that these students consume. It’s axiomatic that many students will seek “marketable” majors and “easy As”, but, for poorer students, the course of their college education dictates whether they will maintain or transcend their parents’ social class.

Students with limited finances are rarely less motivated or intelligent than wealthier students, but they lack traditional freshman-year experiences because of attending two-year colleges or being commuters at four-year schools. Further adding to their isolation, almost all students have jobs, most working more than 20 hours a week, and many live at home to save money. Onerous familial responsibilities, such as caring for siblings, parents or grandparents, commonly negate the emotional benefits of having access to a family support system.

Although mental health remains a pervasive and pressing issue for higher education, we cannot focus on aetiology while income dictates treatment. Marginalised Gen Z students certainly are not delicate, but wealthy students often benefit from rapid diagnosis and private therapy, instead of suffering untreated or enduring long waits at impacted campus resources. And although I am not directly blaming social media for mental illness, it too disproportionately affects lower-income students. Despite their sophistication with consumer culture and media trends, social media leaves many feeling – in the words of a former student – as if everyone else is “winning at life”.

How can we mitigate the imbrication of these students’ challenges? Primarily, we must dismantle their isolation by normalising their experiences, justifying their commitment, acknowledging their struggles and creating spaces for them to fail safely. Value their time, avoid assumptions and don’t waste their money. Avoid busywork by developing activities and lecture points related to their majors or “real-world” scenarios. Set open access texts or put the required reading on reserve in the library. Use group work not only to ensure participation but also to aid in the cultivating of friendships and the sharing of advice. Create assignments and dialogues that reduce risk aversion.

I frequently exhort my students to avoid generalisations, and I strive to practise what I preach, eschewing assumptions about their access to quiet study space, personal computers, reliable transportations or stable family life. But some assumptions can be useful in advocating for our students. We should provide ways they can salvage their grades by accepting late work, allowing revisions to major papers and offering extra credit assignments. We should post a food insecurity clause in our syllabi, insist on inclusive language in the classroom, and use our power, albeit limited, to ensure that they gain equitable treatment from campus services and departments.

It may be idealistic to galvanise a sense of educational entitlement, with fewer intersectional barriers to success. Perhaps, though, we can use authentic connection and refined pedagogy to neutralise classist assumptions about the temperaments and abilities of Gen Z.

Monica Urban is an assistant professor at the College of the Sequoias, California. She was a Houston Writing Fellow at the University of Houston.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The truth about teaching Generation Z

There will be a session on teaching Generation Z at the THE Live event in London on 27-28 November

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login