English studies is arguably the archetypal humanities subject in the anglophone world, steeping its students in the English language’s central cultural landmarks and preparing them for all manner of interesting careers in the arts, media and civil society.

Yet, in an era of increasing fees and instrumentalism, concern about how much the subject really contributes to employability has combined with growing distaste for long, difficult texts written by dead white authors to push down enrolments and endanger departments.

Meanwhile, technology, literary theory and the growth of identity-based subdisciplines have driven such a ramification of research directions that some question what, if anything, defines English studies. Is it really a discipline at all, or just a bundle of more or less related intellectual interests, all obliged to dwell under one historic roof? And is that multifariousness a strength or a weakness?

Here, seven academics from every corner of the English-speaking world give their views on where their discipline is headed – and whether, with that destination in mind, it would be better to step on the accelerator or the brake.

‘Being an English professor has increasingly become a misnomer’

Studying English isn’t what it used to be. The classes many of us of a certain age had in our college days – a survey of Shakespeare or Milton, the 18th-century novel, literary criticism and theory and the like – have given way to courses on identity, Marxism or the global south. In addition, film, television and digital media have come under the English department's capacious aegis. Because of austerity measures, many other disciplines have also come to be housed in English, including creative writing, non-fiction prose, rhetoric, global anglophone literature and linguistics.

It’s probably true that being an English major or an English professor has increasingly become a misnomer. English departments have responded to dwindling student recruitment by not only treating all global anglophone literature in the same course, as my own has done, but also by incorporating literature from other languages in translation – without considering themselves to be comparative literature departments. A better, though inelegant, name might be the Department of Literature and Other Non-literary Things in Many Languages.

English departments might be seen, also, as semiology departments involved in studying the signs and meanings of such things. Cultural studies, which was often housed in English, has risen and fallen as a trendy topic. Now the idea that one should study the semiology of culture is so built into the system as to be invisible to the ordinary student.

The inclusion of transgender, queer and disability studies into the curriculum has broadened the longer-standing categories of race, class and gender, as well as LGBT studies. Intersectionality has become a watchword, if even now increasingly contentious, for identity studies in English. The area of tension is between those who would anchor the origin of the term in the politics surrounding black women and those who seek a wider application to a variety of subject positions. However, the general principle involved in intersectionality seeks to link practitioners to a broad array of political and interpretative activities. You can’t be an English professor in your ivory tower. Rather, the imperative is to fight for and with all the struggles of marginalised or oppressed people. That can be difficult at best and exhausting at worst.

In some senses, therefore, intersectionality goes against a narrowly defined intellectual activity like English studies. To some, English (and the language to which it is linked) is seen as yoked to an oppressive history of conquest, enslavement and imperialism. Hence, another feature of the moment is decolonising the curriculum. This reshaping of the canon of literature now includes paying attention to the global south. It also means reconsidering the European basis of English culture, to the extent that foundational texts like those of Plato or Aristotle are being challenged as “white” and “Eurocentric”.

There have been some reactions against this whirlwind. One approach is to focus on the data aspect of texts. Using algorithms, scholars investigate what kind of signals appear under which conditions. Commonalities between texts can be verified by counting the frequency of certain words, and questions of authorship can be settled by coming up with verbal fingerprints, as it were, for individual authors.

Another reaction is to go back to what Roland Barthes called “the pleasure of the text”. With the advent of “new criticism” in the 1950s, the role of the reader’s enjoyment of the text was eschewed in favour of formalist rigour. It had become a common move on the part of professors to repress a student’s statement “I liked this text” or “I didn’t like this text” by saying, “It’s irrelevant whether you liked or disliked the text. What’s important is to analyse the text.” Close reading is the particular modality of some scholars’ re-embrace of pleasure, and since it is formalist in nature, it seeks to dodge political bullets.

But the days when theory was king were heady days indeed, with students flocking to learn the secrets of complex postmodern orthodoxy. It is hard to see what flagship ideas now lead the way to the seas of enlightenment, and this lack of direction may have been a factor contributing to declining enrolments in English graduate programmes.

Another discouraging factor might be tied to the incredible level of student loans accumulated by would-be English PhDs. After graduation, there are few attractive avenues for erasing debt. Teaching jobs in English tend to be low-paying ones, further degraded by crushing workloads. It has become a routine part of PhD training, therefore, to promote jobs in other professions – editing, marketing, advertising and the like, in what might be seen as a bait-and-switch for those who thought they’d end up teaching in institutions of higher education.

All of that notwithstanding, there are still many students who do find teaching jobs that remind them why they went into the profession in the first place. And the rise of unions for graduate students, teaching assistants and faculty hold out hope for better working conditions. That might well improve the state of English in general.

Lennard Davis is distinguished professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago

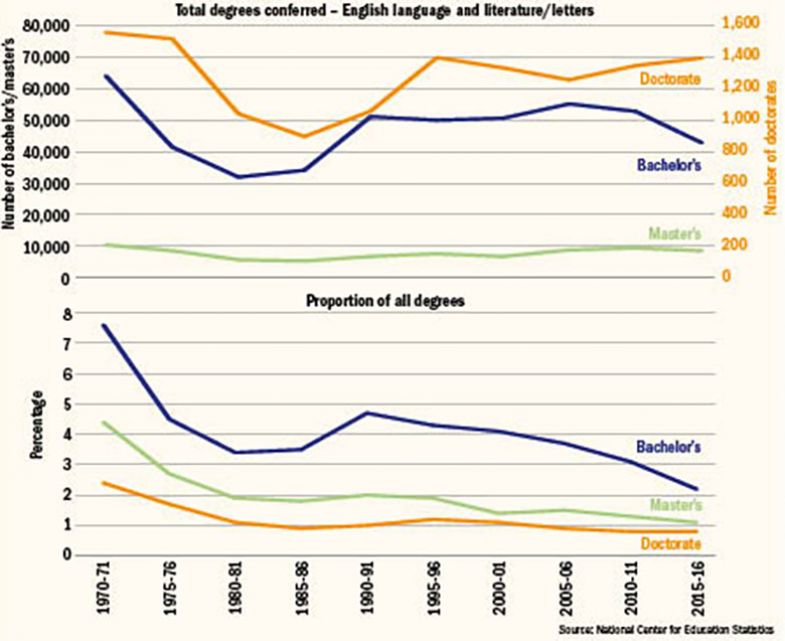

Diminishing numbers: number of US English degrees awarded, 1970-2016

‘A course filled with triple-decker tomes is unlikely to attract big enrolments’

In Australia, as in the US, the discipline of “English” remains a surprisingly resilient colonial residue. Its very name evokes the literature of empire, and it is still often taught in periods whose names tell a triumphant tale of Western progress, from the “Dark” Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, into the Enlightenment and beyond.

Decolonising this curriculum involves, in the first instance, reading and teaching Aboriginal literature. This seems only the most minimal recognition due to the original custodians of the land our universities occupy, and it carries with it the benefit of introducing students to Indigenous stories and ways of knowing that have sustained this country and its ecosystems for more than 100,000 years.

In order to understand how the canon of English literature was (and continues to be) produced, however, it helps to view that process as contingent, as subject to historical forces, rather than independent of them. The past 50 years have seen curricula expand cumulatively, via the addition of a multitude of modules, including women’s, queer and hyphenated literatures (such as African-American or Asian-Australian). But unless we interrogate the claims of the canon itself, this process can end up merely supplementing a centre whose white, Western maleness remains relatively unchallenged. Ironically, the decline of the discipline itself, with English departments only a fraction of the size of those many of us trained in, has done more to destabilise the canon than many more purposeful and politically driven reforms have done: shrinking staff numbers make it impossible to do justice to both the classics and the so-called special interests, creating unavoidable holes in our coverage.

Yet the loss of a mythically comprehensive curriculum has been bemoaned at least since the Renaissance (my own period of specialisation), and no doubt earlier still. So, too, has the loss of that beloved object, the book. In Tudor England, the advent of the printing press was heralded as a cultural catastrophe that threatened the manuscript in much the same way as the digital revolution has been thought to imperil the printed book.

And the declining reading habits of our young people? Fake news, people! Unfortunately, this accusation is bandied about by universities themselves, in justification of their efforts to economise on things such as library facilities and face-to-face teaching. The proverbial short attention span of millennials might well be a myth expressly fabricated by university administrators intent on flipping our classrooms out of existence.

If we flip this mindset instead, we might consider that millennials, and their younger siblings, are actually prodigious readers. It’s just that the objects they read are not necessarily, and certainly not only, conventional books. This does not mean that they categorically refuse to read books. A brilliant long novel, or even a fascinatingly bad one, will probably always find a place on a carefully curated syllabus. A course filled entirely with triple-decker tomes, however, is unlikely to attract big undergraduate enrolments. The challenge today is to situate the novel (or the play, or the poem) in a continuum of textual production that takes into account a variety of modern literary forms, including the digital.

For university English departments to attract and retain these students, we need to realise that reading – like the book-as-object and university-as-institution – has a long history of cultural change: a history about which, not incidentally, cognate disciplines such as cultural studies, the history of the book and the digital humanities, have much to teach us.

If we insist on a limited and limiting idea of the textual object, we risk misrecognising and underestimating the digital reading habits of new generations of readers. If this discourse is not as economically and cynically motivated as I’ve suggested (although the jury is still out on that), it is at least misguided in the extreme: one may as well berate baby boomers for casting off papyrus in favour of paperbacks.

Trisha Pender is an associate professor of English at the University of Newcastle, Australia

‘English research is thriving – but recruitment is declining’

English, a three-legged stool made up of the study of English literature, language and creative writing, is in fine intellectual health.

The study of literature – my neck of the woods – lives through controversy and dialogue: its image, a legacy of the “theory wars” of the 1980s, is that there are wave after wave of new critical ideas, each one sweeping in with a new generation. But under the waves are older, more powerful and more stable currents: the two great streams are (roughly speaking, because the names metamorphose) historicism (“context is all”) and formalism (“read the words on the page”). For the past 25 years or so, the historicists have been dominant: in part, this is because historicism goes with the grain of prevailing intellectual trends – critiquing, contextualising – and in part because it’s easier to get a grant for archival research than for more “blue sky” conceptual rethinking or literary revaluation.

But perhaps the tides are changing. Books like Rita Felski’s The Limits of Critique, Deidre Shauna Lynch’s Loving Literature: A Cultural History, Caroline Levine’s Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (all published in 2015) and Joseph North’s polemical Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History (2017) have all been making a case against historicism and “critique”, and for something like an updated version of old-fashioned criticism: a practice, as North writes, concerned with art, form and feeling, less interested in exposing what a text fails to do and more about using literature to reconfigure our own perceptions.

How this goes along with “decolonising the curriculum” is a matter for critical debate – as in, for example, Ankhi Mukherjee’s prizewinning What is a Classic? (2010). It is hard to tell, too, quite where digital humanities sits between these sides: Martin Eve’s forthcoming Close Reading with Computers uses the best of both – as all great criticism does, really. The critical interest lies where the turbulence of two currents meeting disturbs the sediment.

The study of language is thriving, too, aided, of course, by the digital revolution. There is especially interesting research in stylistics, which crosses over between literary and language study and in sociolinguistics. Creative writing is also transforming English. Traditionally, it brought big beasts into the academy (“What next?” asked linguist Roman Jacobson on hearing that Vladimir Nabokov was being offered a chair at Harvard University. “Shall we appoint elephants to teach zoology?”), but the huge recent influx of writers has begun to shift the critical question from “what does a text mean?” to “how does it work?”. And there is a crossover between creative and critical writing: new master’s degrees and successful small presses like Norwich’s Seam Editions (“Creative-critical publishers”) experiment with ideas of what literature is, or might be.

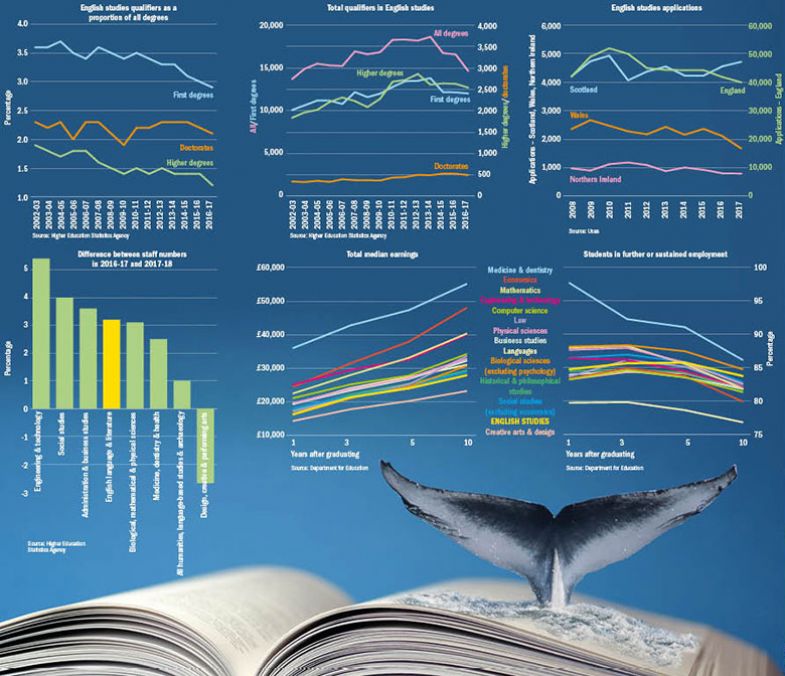

Institutionally, however, English in the UK is a little less rosy. While still the biggest arts and humanities subject, there has been a decline in student numbers from 2010’s high of 60,390 applications and 10,020 acceptances to 47,110 and 8,810 respectively in 2017. This drop is steeper than the current “demographic dip” although it is far from confirming the media’s beloved “death of the humanities” narrative. At a workshop on recruitment organised by the UK’s English Association last year, we found three things.

First, there’s evidence that, at GCSE (school exams at age 16), the current focus on assessment, at the expense of a broader literary experience, puts students off. Could we in higher education do more to help schools engage with the wealth of the discipline, and campaign for a richer variety of texts and the return of coursework – traditionally a strength of the subject?

Second, the removal in 2015 of the cap on the number of undergraduates that English universities can recruit, combined with students' over-reliance on league tables – which serve English less well – has meant that higher-tier institutions have hoovered up undergraduates from lower-tier ones. English is cheap to teach – no labs or expensive equipment are required – so it is a prime vector for quick expansion (even though such growth can have a negative effect on National Student Survey scores).

Finally, while our students are passionate about the subject, we need to stress how employable they are by correcting wider misconceptions. As the below graph shows, English graduates perform very well in sustained employment in the longer term: over the same period, while their salaries are less than some directly vocational courses, they have parity with many similar subjects. Even more encouraging was “Project Oxygen”, Google’s huge study of the most significant skills for a successful career. These include empathy, communicating, listening, critical thinking, problem solving and connecting complex ideas – all of which are embedded in the study of English.

Coding might get you a first job, but an English degree makes your career.

Robert Eaglestone is professor of contemporary literature and thought at Royal Holloway, University of London, and co-editor, with Gail Marshall, of English: Shared Futures (2018)

The big picture: patterns of applications, qualifications, staffing and earnings for English studies in the UK

‘Students exercised by decolonisation show us a new way of opening out English studies’

Ask many UK English literature academics a question about the future of the discipline and they will turn their eyes skywards in exasperation and despair. Numbers of applicants to most English studies degrees are falling. And while the removal of the cap on student numbers in 2015 has allowed some departments to stem the decline, the knock-on effects have also only hastened it elsewhere – prompting regular worried huddles over the departmental coffee machine.

Target grades are lowered, but still courses are closing down – and so, inevitably, jobs are under threat. English literature, one of the most popular areas of the humanities until very recently, now struggles in particular to attract male students, and those from ethnic minorities especially. There are no jobs in studying English, I hear again and again from my students, even at a privileged institution such as mine. How, they ask, does reading books prepare us for careers in the real world? How do these long poems you prescribe set us up to deal with pressing social issues in the ways that “real disciplines” like law or even history do?

As if these were not body blows enough, in recent times the subject has been hit by a further set of challenges from a different direction. However, I’d like to suggest that these represent more of an opportunity than a matter of concern. Approached as a prompt genuinely to consider how English studies might matter (or matter again) to today’s young British readers, they provide us with a way of refreshing – if not completely overhauling – our subject and mode of textual interpretation. And this could be a really good thing.

I am speaking, of course, of the actions and questions generated by the loosely related “decolonial” movements that have emerged since 2015, including “Why is my curriculum so white?”, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall. And while their reach has been cross-disciplinary, the English students involved have invited us to ask fundamentally important questions about what might be called the diversity of our syllabus, and the representativeness of the texts we teach.

How might English literature count to those outside its traditional provinces of cultural and national appeal? How is it that a syllabus excludes by merely reflecting the image that a certain national elite in power around six decades ago projected on the discipline?

Lying behind words such as “decolonial” and “diversity” are crucial concerns about how we identify through our reading, and how our reading might guide us in addressing current issues of social inequality and injustice. Those black British students who have not yet deserted the subject for more obviously “useful” ones have raised questions about how their reading speaks to their experience of the world. Many students now feel that they cannot “find themselves reflected” in standard “Englit” course content. Even in 20th-century courses, there are not enough texts by black and other minority writers. There are certainly insufficient theoretical approaches of non-European provenance – 18th-century black readings of Coleridge and Wordsworth, for example.

Yet in this gap between expectation and delivery lies the opportunity for English that the decolonial movement represents. Indeed, we might feel grateful to the students exercised by these matters for raising the question at all. They show us a new way of opening out English studies – or, some might say, of reasserting the importance of the kind of postcolonial work that some critics have been doing for decades, even if it was never in the interests of the mainstream properly to recognise it.

“If we open the canon,” the British Pakistani author Hanif Kureishi recently wrote, “we also open our minds.” On top of that, we reopen our field for a new generation of students who may well be drawn back to it if it speaks to their subjectivity and hopes of changing the world.

Elleke Boehmer is professor of world literature in English and director of the Oxford Centre for Life Writing, based at Wolfson College, Oxford. Her most recent book is Postcolonial Poetics

‘We need to make our students feel that they will gain skills, knowledge and confidence’

During the past five years, the English curriculum at the University of British Columbia has expanded into transnationalism, media studies, film, science studies and genre fiction. We have also introduced a new programme in language and literature, and have developed an introductory course using a dynamic collaborative pedagogy. We started programmes that include practical work experience for undergraduate and PhD students. We hired colleagues in Canadian, modernist, transnational and indigenous literatures and are now hiring in media studies, cognitive linguistics, critical race studies and African diasporas. We produce field-defining research, placing us in the top 30 English departments in the world.

But enrolments have slumped. Since 2005, our total majors have reduced by 41 per cent. Our university’s commitment to scientific research and international recruitment does not favour the humanities, but such declines are common across many English departments.

It is often suggested that the economic recession of 2008 led many parents to encourage their kids to enrol in programmes that ensure reliable and steady jobs. But is this the only reason for the current crisis?

Last year, we surveyed a cross section of our students to ask why they decided to become English majors. Overwhelmingly – at a rate of close to 100 per cent – they said it was because they “loved literature”. In contrast, only 50 per cent of majors and honours students selected “potential career pathways”, suggesting that, at the time of declaration, students were more likely to select the English major out of enjoyment, without considering career potential. Training in writing and research and the opportunity to participate in work experience were among the least selected reasons.

Yet, when we asked our majors which classroom activities they thought were “most effective helping to achieve academic goals”, they selected essay writing and class discussion. The difference here is striking: at the point of declaring the major, only half of our students are aware of the skills they will develop; once in the programme, they become fully aware that they are learning these skills.

Responses to another survey of close to 400 first-year students from across the university enrolled in our introductory courses were also interesting. Asked if they would consider becoming English majors or minors, more than half said they would never consider English as a primary major, citing a perceived heavy workload, high expectations (especially around writing ability) or personal unsuitability. Only a quarter said yes, with love of literature again being the main reason. But a third said they would consider English as a secondary major or minor because they found the material intriguing, because the professor was enthusiastic and engaged, or because they sensed that the programme would help them develop practical skills.

After assessing these results and comparing them to recent research in the psychology of major selection, we concluded that declining enrolments in English have little to do with the content of what we teach or the methods we use to teach it. Students’ choice of major is an affective choice, as well as an intellectual and practical one.

What is to be done, then? Despite our extensive curricular revisions, we are convinced that neither they nor “skills-oriented learning objectives” will bring students back to English – especially after 2021, when our Faculty of Arts has decided to cancel its long-standard literature requirement. We recognise that students who select a major because they love the subject do so because they also have the economic wherewithal to assume the employability risks that such a choice might entail. We also know that other students are reluctant to enrol in English because they are anxious about the discipline’s usefulness for their careers – even if they stop worrying about that once they have selected English as their major.

Our students become particularly animated when we expose them to the diversity of our research practices. When we are confident about the value of literary, linguistic and humanities research in our increasingly complex, uneasy world, our students feel confident about it too. What we need to do, then, is to find ways to make students feel that they will gain skills, knowledge and, above all, confidence just by being in our programmes.

Encouraging such feelings won’t be easy. Happily, though, we are familiar with the techniques. In our work and in our teaching, we value the complexity of literary and other forms of representation and show how that complexity can be marshalled to positive, social ends. Whether this comes about through academic critical essays or creative group presentations, it still models the kind of engaged work that university graduates will be expected to do.

Sometimes our teaching involves admiration, even love, for the literature – love has been a feature of literary discourse since the 18th century – but it is not all that we teach. We need to communicate intellectually and embody affectively the confidence that what we already teach – complex knowledge and practical skills – will enhance students’ lives every bit as much as it does ours.

Alexander Dick is an associate professor and chair of the majors programme and Patricia Badir is a professor in the department of English language and literatures at the University of British Columbia

‘Relevance to the Hong Kong and China context is crucial’

Hong Kong society often prides itself as the centre of English proficiency in eastern Asia. Its universities’ English syllabi, accordingly, delved much deeper than elsewhere on the continent into the traditional literary canon.

In terms of international perspective and academic freedom some of Hong Kong’s English sections may still be second to none in Asia. But two things have changed. One is the rise of the top Chinese universities, some of whose English syllabi are now, possibly, more intense than those at Hong Kong’s best institutions. The other is the broadening out of curricula in Hong Kong, in pursuit of student enrolments.

Even though a minuscule number of Hong Kong students take English literature as a subject for the state exams at the end of secondary school, English still has the second highest intake each year among all humanities subjects in my university, with only Chinese language and literature taking in more students. Most English departments have both literature and linguistics sections; students take courses in both and can specialise in either. However, in the English literature sections, the main focus may no longer be on bringing students up to speed in terms of the traditional canon.

While elective and compulsory courses in traditional areas such as Romanticism and modernism are still quite popular, change is being driven by the fact that English departments must shape their offerings to the needs of society and students. For instance, they now get money for attracting students from outside their discipline. Hence, they must devise general education courses that can attract such students; we now have very popular modules in superheroes, crime fiction and popular song. Courses in topical cross-disciplinary areas, such as the medical and digital humanities, are also popular.

Whether they boost student employability is another matter, but that is certainly universities’ hope. Both staff and departments must now demonstrate the “impact” of their work, leading to a rise in courses that give students an advantage in the workplace. But it is complicated. With the glut of new MAs in Hong Kong and new short transfer programmes, their primary degree is no longer a great predictor of where someone will work, and surveys suggest that English graduates end up scattered across the employment sector. Still, all programmes are being asked to start internships for students, so we in English try to work with charities, galleries and other cultural organisations where we have connections.

Impact has also become the big determinant of research success. Since impact can be demonstrated by testimonials and outreach activities, research that engages with the public is increasingly important. However, since English is not integral to life outside the university, either in Hong Kong or mainland China, proving impact is difficult. Outreach activities for English department lecturers, for instance, are often limited to school visits and readings at the vibrant local creative writing groups.

Another major factor determining the nature of research in Hong Kong English departments is relevance to the Hong Kong and China context. Nearly all research funding in Hong Kong comes from the University Grants Committee (UGC), and all eight UGC-funded universities compete for the biggest cut of the budget. However, it is almost impossible to win a research award by focusing solely on an anglophone writer.

Between 70 and 80 per cent (sometimes more) of research grants awarded each year in the humanities focus on topics related to Hong Kong or China. The Belt and Road project, for example, has been targeted from all kinds of research perspectives in Hong Kong humanities departments. Academics with specialisms in English literature and language must likewise be very creative in terms of fitting those specialisms into the needs of communities in both Hong Kong and China – especially with the Chinese government now making more funding available to Hong Kong researchers.

English departments also offer important spaces for work in creative writing, comparative literature, world literature and world Englishes. And lecturers and teachers are creatively enhancing the role that it can play in the community through creative writing, practical skills workshops and comparative cross-cultural projects.

English will, of course, never occupy the place it once did, when Hong Kong was a British colony. But the fact that the academy itself still prioritises research in English over, for example, research in Chinese means that English will always have an important place in the Asian university.

Michael O’Sullivan is an associate professor in the department of English at the Chinese University of Hong Kong

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Brought to book: the state of English studies

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login