Carlos Flores describes himself as a “creation of prison”. He was conceived during one of his mother’s conjugal visits with his father, a convicted murderer. And after a predictably troubled childhood, he ended up with his own life sentence.

However, thanks to a rare college programme operating with volunteer support at California’s San Quentin State Prison, Flores has turned things around considerably. Studying Homer, Aristotle and Shakespeare, he earned an associate’s degree at San Quentin. Now, following his release, he is starting his own business and helping dozens of his fellow former inmates down the same path, training them at the local bakery that earlier took a chance on him.

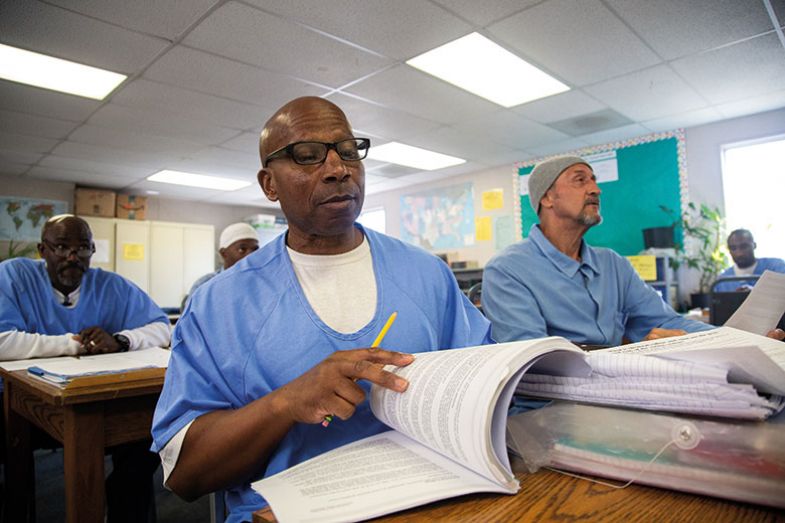

“Aristotle wishes he had the richness of this life,” Flores says. And he puts his enviable position entirely down to the San Quentin Prison University Project. This offers 20 courses each semester in the humanities, social sciences, mathematics and science, as well as college preparation courses in English and maths. Providing such courses to inmates, Flores says, changed a prison ridden with gang violence into a place of deep personal reflection and extensive, life-altering behavioural improvements. If you learn about the world and its history, Flores explains, “you can’t help but learn about yourself”.

Yet it is still unclear whether the US – with easily the world’s biggest prisoner population and one of the worst records for treating them – has learned its own lesson from the San Quentin experience and is ready to let prisoners elsewhere enjoy the same transformative experience.

There are some encouraging signs. Just as both major political parties cheered a get-tough-on-crime approach in the 1990s that crushed even modest efforts in prisoner education, both now seem to be recognising the mistake.

The US currently holds more than 2 million people in prison, the result of an incarceration rate six or seven times higher than that of most western European democracies, despite similar rates of crime. With an institutional emphasis on punishment rather than rehabilitation, educational services in US prisons are minimal and college-level options rare. But Americans are telling pollsters that they overwhelmingly support the idea, common in other advanced countries, that the criminal justice system should be designed to help inmates be productive citizens after their release. And federal and state inmate initiatives are sprouting up, bolstering a smattering of charitable models for prison-based higher education.

As well as the San Quentin project – originally a unit of the Oakland-based for-profit institution Patten University but now in the process of acquiring independence – Bard College runs a liberal arts programme, offering associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, in six prisons across its native New York state.

The political winds also appear to be blowing more favourably, amid congressional moves to reconsider the 1994 ban on inmates receiving federal aid for tuition fees – which resulted in almost all of the 300 prison-based college programmes established at that time closing down.

In 2015, the Obama administration awarded San Quentin’s Prison University Project the National Humanities Medal, and acted on its own to restore for inmates a limited use of Pell Grants – the main federal subsidy for low-income students attending college – by using some funding allocated for small-scale experiments. The 12,000 inmates a year that are benefiting represent a mere sliver of the need, given that most US prisoners meet at least minimum academic qualifications for college, according to a study published earlier this year by the Vera Institute of Justice. But it may be just the beginning. After initially criticising Obama’s experiment, Republicans have warmed to the idea, and rejected proposals from within their ranks to kill it. Influential conservative titan Charles Koch is a strong advocate of inmate education, and the Trump administration – despite a government-wide pattern of ending programmes associated with Obama – has allowed the experiment to continue, and even mooted expanding it.

Much of the political impetus appears to be a matter of highly belated self-interest. The US policy of mass incarceration costs taxpayers at least $80 billion (£63 billion) a year – and probably much more. Nearly all US inmates will be released at some point, but with little policy aimed at helping them during or after their confinement, the majority will struggle to survive and will be jailed again.

By contrast, the Bard Prison Initiative reports a recidivism rate of 5 per cent among those who took some of its classes, and 2 per cent among its graduates; across the state, about 42 per cent of prisoners released in 2010 returned to prison within three years, the majority for parole violations. San Quentin has reported a recidivism rate of 17 per cent, compared with 65 per cent statewide. And a 2013 synthesis by the Rand Corporation of 11 studies of various types of inmate education programmes over the past four decades found that recidivism rates among participants were 13 percentage points lower than among those who did not participate.

That should make clear the benefit for taxpayers, says author and activist Christopher Zoukis. He had no access to such a programme during his 12-year prison stretch for a non-violent computer-related crime committed as an 18-year-old; despite that, he completed two college degrees by correspondence from his cell in Virginia; he is now pursuing a third following his release, while remembering those he left behind.

“Do you want your future neighbour learning how to brew prison hooch for 10 years, or do you want him going to school?” Zoukis asks. “I can tell you the answer for me and my neighbours.” The data comparing education with recidivism are “just so clear”, and withholding college from inmates is “a recipe for a life wasted”, he says.

Christopher Zoukis at his graduation from Adams State University, Colorado

Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, Levy Institute research professor at Bard and a distinguished fellow of the Bard Prison Initiative, agrees. She cites a Rand estimate that the recidivism reductions entail a $5 benefit for every state dollar spent on higher education behind bars. “It is the one sure thing we know how to do to cut recidivism,” she says. “It's been proven over and over again.” Hence, “It's one of the very few issues at the moment that draws bipartisan support.”

But the consensus may not last. Some advocates fear that the recidivism argument is being taken too far. Mary R. Gould, an associate professor of communication at Saint Louis University who is now serving as director of the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison, warns against Rand-type analyses being “weaponised” by policymakers focused on short-term costs. That kind of thinking, she says, leads lawmakers to try to identify “the right dosage of education” for inmates.

In an article last year in the Journal of Experimental Criminology, experts including two Rand authors used exactly that language. “Is it sufficient”, they ask in the paper “Does providing inmates with education improve postrelease outcomes? A meta-analysis of correctional education programs in the United States”, “that an inmate receives 10 hours of academic instruction a week or is 15 hours of academic instruction required to reduce recidivism? Such questions of dosage are especially salient now, when many correctional education programs have experienced significant budget cuts.”

Gould does not deny that a reduction in recidivism is an important benefit of college in prison, but she argues that since it is not an educational measure it shouldn’t be used to determine approaches to inmate education, any more than it is used to determine approaches to college education in general. Lawmakers should, rather, contemplate providing and funding college for prisoners for the same reasons that apply to all Americans.

The recidivism statistics may also be skewed by the fact that inmate education programmes draw most of their students from among those inmates least likely to reoffend anyway. Indeed, even Max Kenner, the founder and executive director of the Bard initiative, is wary of judging his programme by its low recidivism rate, since it may imply that “we’re not taking suitable risks” on who it recruits. “How far can we push the envelope? That should be our business,” he told non-profit criminal justice news organisation the Marshall Project in 2014.

As a youngster, Flores seemed about as high-risk as they come. Eight years after he was born, his father killed himself. Around that time, young Carlos was diagnosed with bone cancer and endured gruelling chemotherapy. Not long after that, his mother suffered a serious brain injury in a motorcycle accident, leaving him to care for her as they moved from place to place across California. At some point, she added an abusive boyfriend to the mix. “School is not in my wheelhouse,” Flores recalls thinking then.

Around the age of 15, he moved to southern California to stay with a brother, but was denied admission to a local high school because his hair was braided – a possible marker of gang membership. So he moved back north to his mother, but didn’t go to school there either. Then a friend suggested a robbery. That turned deadly and, at age 16, Flores got a life sentence as an accessory to murder.

That began a life of home-made knives, survival amid violence, denied parole reviews and repeated prison transfers. It all brought him, finally, to San Quentin, whose donor-funded Patten University unit was being shaped by a college instructor named Jody Lewen into a nationwide model for higher education behind bars.

A tenth of San Quentin's 3,500 inmates are now enrolled, with months-long waiting lists. That kind of enthusiasm wasn’t easy to generate among a population hardened against any notions of genuine compassion.

“At first I didn't trust her as far as I could throw her,” Flores admits. He thought Lewen – now executive director of the Prison University Project – was “some kind of rat snitch, telling on people, in collusion with the authorities, to somehow manipulate us”.

Others around him wrestled with similar thoughts. Many inmates consider membership of a gang – usually formed along racial lines – to be essential to their survival in prison and beyond, often obliging the authorities to arrange prison transfers to break them up. But much of the gang activity stopped when inmates enrolled on Lewen’s programme, Flores says.

“I know some people who have died rather than [leave their gangs] – literally allowed themselves to be killed,” he says. “They would rather die than renounce their gang.” But faced with the choice between doing so and being shipped out of San Quentin and removed from Lewen’s classes, many started to think the unthinkable.

For them, the chance of education “was like a real in-depth self-help course”, Flores says. “It’s such a powerful thing when you get that kind of light...It changes the whole dynamic of the prison.”

Lewen herself recalls one student who, for years, had identified as a white supremacist: part of a mindset that led some white prisoners to refuse, for instance, to pick up a basketball that had been touched by a black inmate. One day, after taking some college courses, he took a moment to tell her about his now-abandoned ideology. “He was realising how stupid it was, that it was childish and irrational,” she says.

Jody Lewen and student Rahsaan Thomas

By the end, Flores had become not only a true believer, but a teacher’s aide. And that’s what finally put him in a position, after years of parole denials, to get released. It happened outside one of the small classroom buildings at San Quentin, when a guard suddenly emerged choking on something he had been eating.

“I thought he was playing at first,” Flores recalled. Then came a mix of emotions, fear chief among them, as the prisoner began pounding the back of the doubled-over guard, realising that it could easily be misinterpreted by other guards in the distance as an attack.

“I could have gotten shot,” Flores acknowledges – or perhaps beaten by inmates for aiding “the enemy”. Yet no guns were drawn, and whatever was caught in the guard’s throat came loose. Flores was promptly given another parole hearing, and within another few months he was free.

Much of the public failure to expect an inmate to show humanity towards a guard, Lewen believes, stems from an inability to empathise with people from such tough backgrounds, in which “bursts of occasional violence” are only to be expected. Much gang activity, for instance, is defensive, she points out: “Most people placed in these kinds of conditions would become violent out of fear or conformity or desperation.”

From his perspective, Flores sees education as a light that “reveals some very impressive men” caught in prison: “people I really admire who just made a bad, bad mistake in their pasts”.

The San Quentin programme’s liberal arts curriculum, heavy on mathematics and English, aims at putting the student in a position to attend any number of public colleges after release. Lewen was delighted by a recent phone call from San Francisco State University telling her that 10 of her former students are starting there this semester.

“I live for those phone calls,” she smiles.

But is a liberal arts education really best suited to the needs of prisoners? Or would a more vocational approach be more appropriate? Or perhaps something else entirely? Researchers remain unsure – mostly because there are so few examples to study in US prisons. To that end, a new report published this month by Lewen and Gould calls for universities to create a greater range of options for inmates and to more carefully study the results, without putting too much emphasis on recidivism as a yardstick. The report, "Equity and excellence in practice: A guide for higher education in prison", is co-written by Tanya Erzen, an associate professor at the University of Puget Sound and faculty director of the liberal arts college’s Freedom Education Project Puget Sound, which runs a college preparation programme for incarcerated women, trans-identified and gender nonconforming people in Washington state.

Right now, for most US inmates – and especially those in federal prisons – the only option is a correspondence course. One of the best is run by Adams State University in Colorado, which has a top-level accreditation. Zoukis took an Adams State bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary studies and a master’s of business administration while at the medium-security federal prison in Petersburg, Virginia. But it didn’t come cheap, and he could only afford the total bill of more than $30,000 with help from his family. That’s not a realistic option for most prisoners, and Zoukis was one of just a handful of Petersburg inmates taking this option – most of them pursue less expensive trade skills, such as in paralegal fields.

Distance learning also suits the current trend in US prisons towards further isolation, with video conferencing technology increasingly being installed for family visits and court appearances. But while such trends may address short-term concerns over cost and safety, distance learning is an especially poor option for incarcerated learners and encourages predatory practices, according to Gould.

Zoukis is concerned that a return of Pell Grants for prisoners could be especially attractive to unscrupulous for-profit colleges. But traditional colleges struggling with budget pressures could be just as likely to exploit the situation, Gould says: “People in prison have always been seen as a revenue stream, and it is a population that won’t demand much.”

Lewen is directly urging policymakers to avoid reviving Pell Grants for prisoners, and to instead create a system that pays institutions based on their performance in prison settings. “Pell is very ill-suited to the prison environment,” she believes. One reason is the requirement in Pell that students take a full load of courses: this may be beyond prisoners' capacity, while the lack of performance-related requirements for colleges would offer them little incentive to maximise the quality of their service. Another concern is that, as a study in Pennsylvania found, only a third of inmates are eligible for Pell, owing to problems such as a default on a previous loan, difficulty obtaining their personal tax records, or failure to register for a potential future military draft. And while their typical entitlement to free schooling in prison up to the secondary level means that most US inmates have a high-school diploma or equivalent, many need remedial education to take college courses, and that cost is not covered by Pell Grants.

Bard’s Lagemann argues that a good college experience in prison doesn’t have to be expensive. Nor is there any problem staffing it, with volunteers plentiful. “The faculty members who teach in the prisons love teaching in the prisons. I don’t think there’s been any faculty member who taught once and never wanted to come back: they all want to teach again, because the students are fabulous,” says Lagemann, a former dean of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

According to Gould, the fundamental point for Americans to understand is that prisons are communities in their own right. And, in that sense, they are just as worthy as every other community of having a civil society populated, run and guided by educated people.

“Prisons are violent and traumatic places,” she says, “but they’re also places where people look out for each other and they take care of each other. And sometimes people live there for their whole lives.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Freedom to learn

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login