The relationship between quantity and quality in academic publishing is a tension that often goes to the heart of research decision-making, whether by policymakers, funders, university managers or individuals.

It is an issue intertwined with the “publish or perish” culture that some academics believe has led to the “salami-slicing” of research into the smallest possible publishable units, in a bid to enhance at least the appearance of productivity. In some countries, academics are rewarded for such productivity, receiving extra payments for each paper they publish. That, in turn, can reflect a national research strategy that rewards volume of output over its quality. And even exercises such as the UK’s research excellence framework that put more emphasis on quality still expect academics to produce a certain volume of research within the assessment period.

Funders, too, are keen on the idea that scientific findings should be disseminated as rapidly as possible: an urge only intensified by the evolution of digital innovations such as preprint servers. And while this does not necessarily translate into an advocation of salami-slicing, it potentially feeds a culture in which some fear that a rush to press comes at the expense of papers that bring together the results of entire, multi-year studies into scientific narratives of genuine depth and significance. History, they note, offers many examples of academic titans who, nevertheless, published comparatively little.

On the other hand, those were different times and it is easy to wonder about how many academics lost to history published even less – if anything. Isn’t it likely that the best minds will be among the most prolific? Equally, isn’t the process of preparing work for publication, and the multiple levels of feedback that it entails, a powerful mechanism by which academics can become better researchers? Could productivity, therefore, also be to some extent a cause of quality?

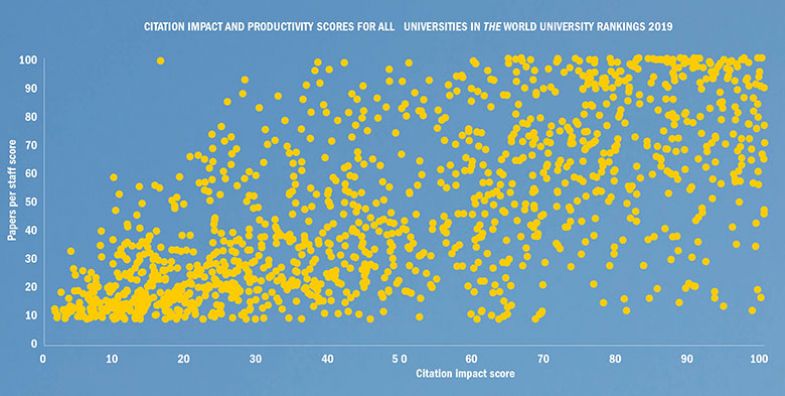

Times Higher Education’s own data suggest, at the very least, that there is a correlation between productivity and quality. Institutions where the most research per academic is being published also tend to be those with the highest citation impact.

Citation impact and productivity scores for all universities in THE World University Rankings 2019

A chart polling every one of the more than 1,000 universities in the THE World University Rankings 2019 shows that the bulk either cluster in the bottom-left or top-right quadrants – areas where universities are either achieving a low or high score for both citation impact and papers produced per staff. However, there are also plenty of institutions that buck this trend.

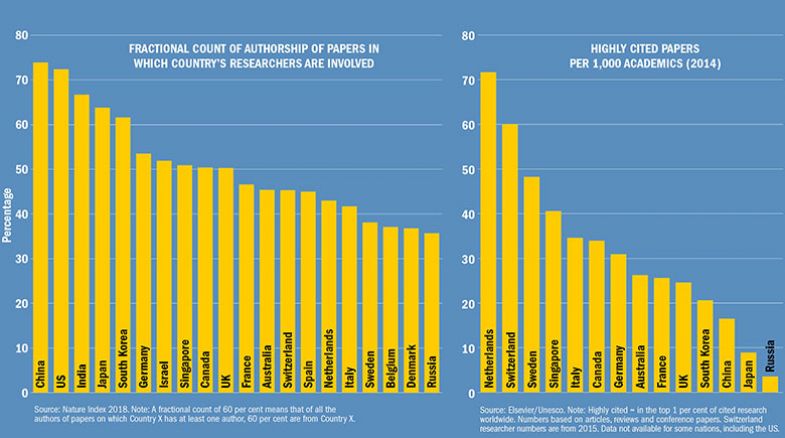

Taken at the national level, this general picture appears to hold, too. Plotting the average scores of countries with at least 10 universities in the rankings shows, again, that producing more research per academic seems to go hand in hand with better citation impact. But the relationship is far from clear-cut. A number of nations achieve average higher citation impact scores than Australia, for instance, despite having lower productivity, while many countries trail Egypt on citation impact despite having higher productivity.

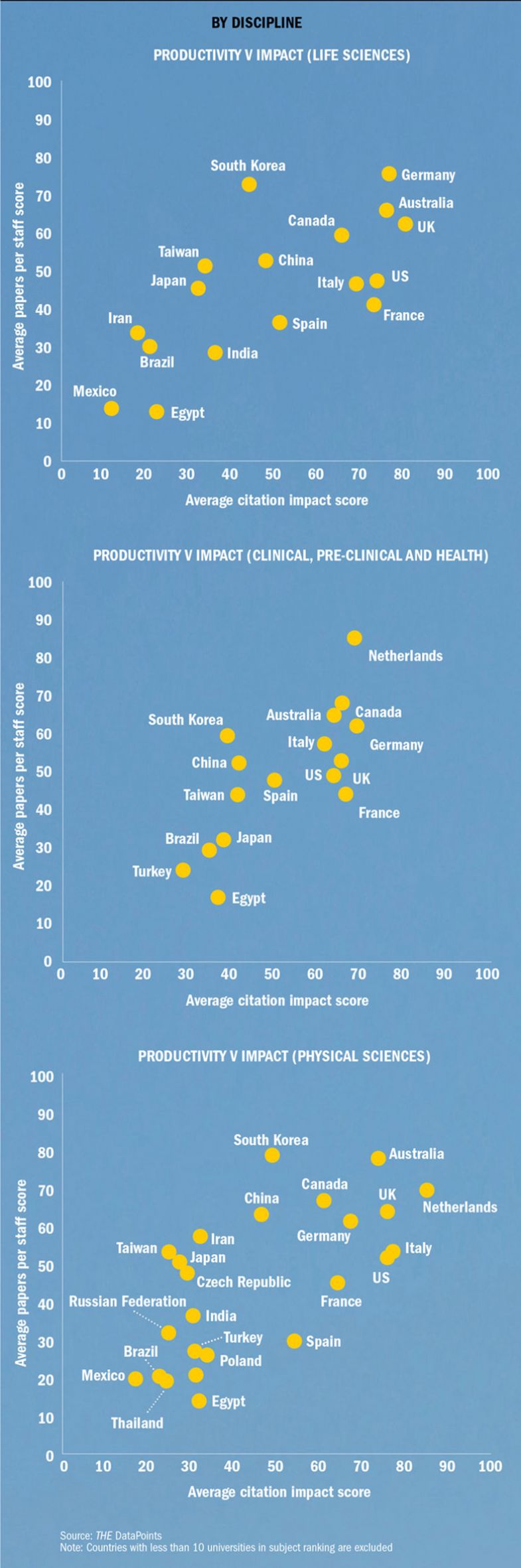

Measuring up: Productivity versus impact

Moreover, these data are far from perfect. They represent only some of the world’s research universities and reflect scaled scores. They also assume that citation impact can be a proxy for quality, an assumption that opens up a huge separate debate about the extent to which such a metric truly reflects the value of scholarly work. But, for what they are worth, the data do indicate some level of relationship between productivity and quality.

This theme of there being some sort of link, but a complex one at best, is a thread that runs through much of the academic research that has been conducted in recent years to examine the issue.

A key paper was published in 2003 by Linda Butler, former head of the Research Evaluation and Policy Project at the Australian National University. The paper, “Explaining Australia’s increased share of ISI publications – the effects of a funding formula based on publication counts”, looked in detail at Australia’s increasing share of world research output in the 1990s and revealed that it seemed to come at the expense of citation impact. The finger of blame was pointed at systemic incentives that boosted volume but not quality.

“Significant funds are distributed to universities, and within universities, on the basis of aggregate publication counts, with little attention paid to the impact or quality of that output. In consequence, journal publication productivity has increased significantly in the last decade, but its impact has declined,” the abstract explained.

The research was a shot in the arm for critics who had been saying for a long time that pushing on quantity inevitably harmed quality. Australian research, more recently, has been assessed on quality, via the Excellence in Research for Australia initiative, first run in 2010.

However, other researchers have been able to show that, at the individual level, there is clear evidence that increased publication rates are often accompanied by higher citation impact. In 2016, Ulf Sandström of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and Peter van den Besselaar of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam analysed data concerning almost 50,000 Swedish researchers and found “a strong correlation” between higher productivity and increased citation impact. In some fields, they discovered a higher probability that each additional paper would gain more citations.

Other studies have suggested that a core of highly cited academics produces a staggeringly large share of the world’s research output and citations – which hardly seems to suggest that publishing more is detrimental to quality.

For his part, Sandström believes that there are enough safeguards in the system to prevent research being salami-sliced to the point that quality suffers, because such papers would simply get no traction.

“If you start to have papers that are very short or with little information, then your colleagues will understand that [they are coming from] a kind of a publication machine. People can fool themselves but I don’t think they can fool their colleagues,” he says.

Complaining about salami-slicing, he continues, “is the sort of critique that comes from those that do not publish, and I am not always sure that we should listen to them. When I look at the really top producers there are very few that don’t have a very high [citation] impact.”

Others believe the research carried out since the Butler paper simply shows that the relationship between productivity and impact is much more complex than previously thought.

Sergey Kolesnikov, a research associate at the University of Cambridge who has co-authored research on the productivity-quality issue, says Butler's “seminal paper” had seemed to confirm “what most scientists concerned with the rise of governance of science through metrics had suspected through their own perceptions and experiences: that excessive productivity was bad for [scientific] impact. However, later advances in scientometrics, research evaluation and, especially, data science have shown that this relationship is ambiguous and much more complex.”

Specifically, says Kolesnikov, studies have suggested that there is “strong variation in the degree and direction of this relationship depending on the factors such as researchers’ age, gender, seniority, career length, number of collaborators, academic discipline or institutional environment”.

In a previous role at Arizona State University, Kolesnikov worked on a study looking specifically at the relationship between productivity and impact in chemistry and engineering, and among different cohorts of academics, defined by when they started their career. The findings, published in 2018 in Scientometrics, suggest that in chemistry – a subject where it is easier to split research into smaller publishable chunks – impact tails off as more papers are produced. But in engineering, where splitting is harder, no such trend is generally observable.

Although the study, “Researchers’ risk-smoothing publication strategies: is productivity the enemy of impact?”, looks at only two disciplines, it is an illustration of how there may be different productivity-quality dynamics operating in different subjects.

Data from THE’s subject rankings also seem to show very different relative performances by countries for citation impact and productivity depending on the discipline. For instance, nations with higher productivity in the life sciences tend to be those with the highest citations. But in the physical sciences and clinical and health, more countries have similar average citation impacts irrespective of their productivity.

Another complicating factor picked up by the academic research is differences in how citation impact is affected according to the career stage of a scholar. Kolesnikov’s research shows evidence that the most productive engineering researchers benefit from a “Matthew effect” of accumulated advantage, whereby their reputation builds up so much that everything they publish at a later career stage gains a large degree of attention.

This is an issue that has been picked up in other studies. A paper published in 2016 in Plos One that uses a huge dataset based on more than 28 million researchers publishing over a 33-year period finds that the more academics publish, the bigger the share of their research that is highly cited. However, the study, “How many is too many? On the relationship between research productivity and impact”, also notes that, depending on the discipline, “such a pattern is not always observed for younger scholars”.

The claim that established academics' accumulated reputation gives them an unfair advantage is voiced particularly stridently in critiques of the h-index. This supposed measure of a researcher’s prowess attempts to encapsulate productivity and citation impact in a single number – denoting, specifically, the number of papers a researcher has published that have garnered at least that many citations. As Jonathan Adams, director of Clarivate Analytics’ Institute for Scientific Information, pointed out for THE last year, because the h-index does not really account for the time taken to amass citations, older researchers in fields where citations are easier to come by have a clear advantage.

The use of bibliometrics to measure productivity is not as controversial as its use to measure quality, but it is not beyond dispute. A paper published in the journal Gigascience last month, for instance, analysed more than 120 million publications written since the beginning of the 19th century and found that researchers who started their careers in 1950 published an average of 1.55 papers over the next decade, while those who started their careers in 2000 published 4.05. But the analysis, “Over-optimisation of academic publishing metrics: observing Goodhart’s Law in action”, also found an increasing trend for papers in the physical sciences to have “hundreds or even thousands of authors” and concludes that "the number of publications has ceased to be a good metric [to measure academic success] as a result of longer author lists, shorter papers, and surging publication numbers."

Vincent Larivière, an associate professor of information science at the University of Montreal who co-authored the above-mentioned Plos One paper, also worked on a separate 2016 Plos One paper analysing the publication patterns of about 40,000 researchers who had published between 1900 and 2013. This also found that, on face value, it seemed that researcher productivity had increased over the years. However, when the number of co-authors was properly accounted for by splitting credit for each paper between them – known as fractional counting – this rise disappeared. Hence the title of the paper: “Researchers’ individual publication rate has not increased in a century”.

The rise of co-authorship means that measures of research volume – whether for individuals, universities or nations – that do not use fractional counting can arguably show distorted results. For instance, if a researcher works on nothing but collaborative papers involving more than 100 authors each time, have they really produced the same amount of research as an academic who authored all their papers alone?

The potential issues can be easily seen by looking at data where absolute and fractional counting are displayed side by side. A good example is Nature Index, which analyses research published in a suite of 82 high impact natural science journals. Its ranking of countries varies according to whether fractional counting is used.

Regarding productivity, the problem can become even more thorny when considering whether authors really contributed equally to a paper, as fractional counting assumes. That is especially true of principal investigators in science, who may not have conducted any of the lab work.

Larivière says the core of the issue is that “in the research system, there is no cost for adding another author to a paper”. As a result, he supports efforts to attribute credit properly at the end of articles to show who did what – including PIs, whose role may still have been vital in securing funding and managing the research. However, for that to help in analysing productivity all journals need to adopt such a format, Larivière says, and the relative contributions “need to be codified in some way”: something that he accepts is very difficult to incorporate into the system.

Larivière’s co-author on his study of productivity and collaboration, Daniele Fanelli, points out that despite their findings that academics are not necessarily publishing more, papers “are becoming longer, more complex and richer with data and analyses”. Hence, he says, “it could be that scientists might have responded to pressures to publish by salami-slicing not so much their publications, as many believe, but their collaborations”.

Overall, Larivière says, the various complexities and problems with bibliometrics mean that they should not be used to analyse individuals’ performance. However, citations can still be “an amazing tool to understand the macro structure of science and to make policies at the global level, looking at institutions [and] countries”.

So what is the advice for university managers and politicians regarding whether they should incentivise productivity or quality?

For Sandström, each disciplinary community rewards the best papers through peer review and citations, and governments and other bodies should keep out of trying to manipulate the system in any way: “You should support your researchers and let them decide how to deal with these things,” he says.

An approach like the REF that restricts the number of publications that universities and individuals can submit for credit “seems crazy”, he adds. He is even critical of guidelines on the use of metrics, such as the Leiden Manifesto. “Why…should we come up with those [rules] that are general for the whole scientific community,” he asks, given the vast differences in practice between disciplines.

Fanelli, too, does not believe that “there can be any general rule that applies to all contexts”, adding that “any policy will have cost and benefits”.

“Concerns for [the] deleterious effects of a publish or perish culture have been expressed, in the literature, at least since the 1950s,” he says. “And the validity of these concerns is obvious enough. On the other hand, a system that did not place any kind of reward or value on the publication activities of researchers would hardly be functional. In general, if an academic is paid to devote part of her time to research, then it is legitimate for her employers to expect to see some results. It is in the interest of society at large, too. Research that never gets published is useless by definition.”

However, Sarah de Rijcke, director of the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University and one of the authors of the Leiden Manifesto, says pressure to publish “becomes a problem when competition for journal publication leads to strains on existing journal space, the proliferation of pay-to-publish and predatory journals, and the manipulation of journal impact and citation statistics. It also becomes a problem for individuals when scientific careers are explicitly designed to emphasise traditional forms of productivity. It is detrimental for science if this numbers game is not balanced with a qualitative assessment.”

De Rijcke concedes that it may have made sense “30 years ago” to incentivise more publishing activity. “But, generally, I do not think today’s academics need external triggers to do something that has become such a fundamental part of the everyday work of being a researcher.”

James Wilsdon, professor of research policy at the University of Sheffield, who led the UK’s own 2015 review into the use of metrics, The Metric Tide, agrees that in developed systems, quantity drivers do not seem relevant any more. In North America and parts of Europe, most academics “have a high level of intrinsic motivation to want to undertake and produce good research”, so it is about organising funding in a way that makes the most of that motivation.

But “there are some systems where you have got more of a problem in terms of a culture of people just not producing…and there you [may] need more extrinsic drivers in the system to try and crank up the volume”.

He says the REF has evolved from its original incarnation as the research assessment exercise in the 1980s – when its mission was more overtly about increasing research volume – to something that is now, he believes, focused on quality and avoiding the wrong incentives.

The move in the latest REF to allow researchers to submit a minimum of just one piece of scholarship “is quite a sensible one because it does recognise that people produce outputs in different forms in and different rhythms...I think volume of papers is a very bad thing to be incentivising: far better to be incentivising people to do fewer but better things.”

So which national systems seem to have got the balance right between quality and quality?

Looking at data on the most highly cited research produced per academic researcher suggests that the Netherlands is one system that others should look to. Wilson suggests this may be because of its diversity of approaches to funding and assessment and also its position in Europe as an “open” system that is drawing talent and collaborations from other countries. But the fact that both the Netherlands and another country scoring well for highly cited research productivity, Switzerland, have high shares of international collaboration raises the question of whether this, in itself, influences the data.

Making your presence felt: authorship and highly cited research

Another interesting question is the degree to which China is moving from a quantity-driven model to a quality-driven one and whether this is a natural development for any emerging system.

Fanelli, whose own studies have identified China and India as “high-risk countries for scientific misconduct”, says this “is plausibly due to academics in some contexts [being] lured to publish by cash bonuses” that they receive for every paper published. In India, for instance, career advancement has been linked to publication since 2010. Only in 2017 did it introduce a vetted list of journals, and only this year did it take steps to remove the hundreds of predatory journals that had been included among the more legitimate ones. However, Fanelli adds that it is in "low ranking institutions that are fighting to emerge" that poor incentives seem to have the worst effect, and it may be a problem that resolves itself as those universities come to realise the futility of attempting to compete on research and switch their differentiation efforts to teaching.

Over the longer term, developing systems like China and India may also benefit from the increasingly detailed analyses being conducted about productivity and citation impact by academics. But whether their policymakers and governments make use of such evidence is open to question.

“Unfortunately, I don't think that there is policy debate happening on this topic,” warns Cambridge’s Kolesnikov. “A stronger mutual dialogue and engagement between scholars and policymakers is needed to put recent advances in the ‘science of science’ – including our improved understanding of the productivity-impact relationship – into policy practice.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Quality versus quantity

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login