Political parties seeking power will often promise to abolish tuition fees in higher education. We saw that in the 2017 UK general election campaign, where the Labour Party’s pledge may have contributed to its doing far better than any poll was predicting. The issue may again have an impact in the current election. In the US, too, leading Democrat presidential hopefuls have committed themselves to eliminating student fees.

But what is the reality behind the rhetoric of this eye-catching policy? In order to answer that question, we can look back to another 2017 election, when the New Zealand Labour Party came into government with a flagship promise guaranteeing all citizens three years of fees-free post-secondary education.

The party’s policy, announced 18 months before the election, promised to phase this in over a six-year period, complementing heavily subsidised early childhood education and 13 years of free schooling. Labour positioned it as a means of addressing persistent skill shortages in the New Zealand labour market. The new government argued that, by removing fees, they would be reducing barriers to study, meaning enrolments would grow and so the skills available to employers. More domestic students would also make up for the forecast drop-off in international student numbers that would result from planned changes in visas. In the lead-up to the election, Labour told institutions not to worry about the loss of international student revenue as they could expect a 15 per cent increase in domestic enrolments in response to the fees-free policy. That was quite a claim.

The relationship between fee levels and tertiary participation

The elasticity of demand for tertiary education is very low – meaning that fee changes don’t affect demand very much. One reason, in the New Zealand context, is that virtually all domestic tertiary students qualify for interest-free income-contingent loans when they enter tertiary education. This means that the cash cost to a student of enrolling in tertiary education is close to zero.

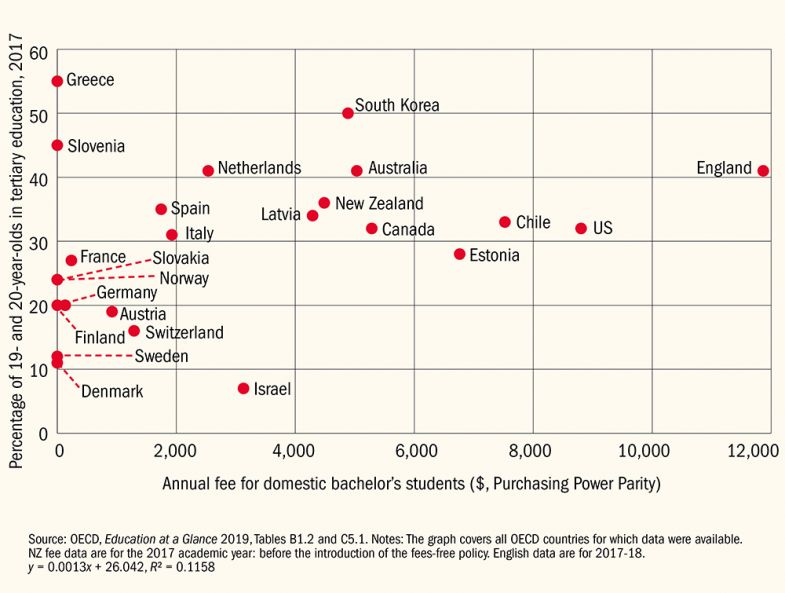

We see a similar phenomenon in nearly all developed countries: fees don’t necessarily deter participation. OECD data reveal how fee levels line up with participation levels. The majority of zero-fee countries in the OECD have a lower rate of participation in tertiary education than New Zealand (or England).

Relationship between participation rate and fees

The graph above shows only a weak relationship between fee levels and participation rates in the core age group for tertiary study. Other factors are much more important in encouraging enrolments. Among the 24 countries whose data are shown in Figure 1, all but two of those whose participation rate is below 30 per cent have low or no fees. Seven of the 24 have zero fees; of those seven, only two (Greece and Slovenia) have relatively high participation rates.

That should be no surprise. It has long been known that there is little relationship between young people’s participation rates in higher education and the level of fees – especially when students can easily access income-contingent loans. Relevant evidence includes:

- When fees in English universities trebled in 2012, enrolments of young full-time students held up

- A study of the relationship between fee levels and participation rates in New Zealand higher education showed that as fees rose, so did the participation rate. This may sound counter-intuitive, but it is still true.

We also know that factors other than cost are the main influences on participation rates:

- Research in New Zealand shows that performance at school dwarfs all other influences on the decision to participate in higher education. Once we control for school performance, other factors play a part: people whose parents have higher qualifications are more likely to enter tertiary education; those who grow up in more deprived neighbourhoods are less likely to enrol (even once other factors are taken into account); and people who use mental health services are less likely to advance to higher levels of education. But family finances turn out not to matter.

- Those findings are echoed in Canada where research has found that participation in post-secondary education is more influenced by cultural factors and the level of parents’ education than it is by finances.

So how did the first stage in the fees-free policy work out in New Zealand?

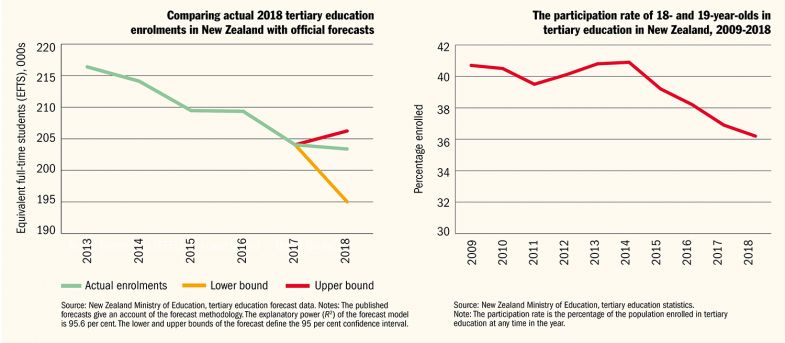

Let’s look at the 2018 New Zealand tertiary education enrolments data and compare them with the government’s forecasts for 2018. Those forecasts – based on enrolment trends up to 2017, demographic data and predictions about the labour market – took no account of the fees-free policy. This means we can compare the actual enrolments in 2018 with what was expected in the absence of the fees-free policy. From this, we can estimate the effect on enrolments of the policy change.

Student enrolments in New Zealand across time

The actual 2018 outcome is within the 95 per cent confidence interval for the forecast – within the margin of error. In other words, the actual result was in line with what would have been expected in the absence of the fees-free policy. That means there was no statistically measurable effect on enrolments from the change in policy. None at all.

Another test of the impact of the fees-free policy is to look at the population aged 18 and 19 – the age group most likely to be affected – and to ask what happened to their participation rates. Figure 3 above shows the proportion of the population aged 18 to 19 who were enrolled in tertiary education over the past 10 years.

The trend in the participation rate reflects the labour market. Youth unemployment remained relatively high in New Zealand in the years following the global financial crisis. But, as the youth labour market began to strengthen after 2013, the enrolment rate began to drop. Fees have much less effect on enrolments than employment factors. The tertiary participation rate continued to fall in 2018, despite the fees-free policy.

If the government were to judge the success of the policy on how it lifted access to post-secondary education, it would have to give itself a fail grade. The report card might read: “Tried hard but made many basic errors.”

The problem of deadweight

Unsurprisingly, student leaders disagree.

The University of Otago Students’ Association (OUSA) finance officer Bonnie Harrison told the education website Education Central that the policy “breaks down barriers and reduces the risk for students from low socio-economic backgrounds…It’s also a step towards education, at all levels, being a genuine public good for all – as it should be – and not a privilege for the few.” New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations president James Ranstead agreed that the fees-free policy has “lowered…barriers”, adding that “financial pressures…correlate to student mental health, which is a huge issue too”.

However, a survey of 1,000 University of Canterbury 2018 new entrants, reported in the New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, found that one student in three claimed that the policy influenced their decision to enrol, while only 5.8 per cent reported that the fees-free regime was a critical factor.

That survey, of course, relies on self-reporting, so it is likely to overstate the true effect. However, even if the figure of 5.8 per cent were an accurate reflection of those whose enrolment decisions were due to the policy, and that figure was applied to all institutions’ 2018 intake, it means taxpayers have had to pay fees for 47,000 people in order to enable 2,700 of them to enrol. That a very great majority of people who benefited from the fees-free policy received a bonus for doing exactly what they always intended to do is the epitome of deadweight. The public value of the expenditure on the fees for the 44,300 was precisely zero.

A regressive policy

Furthermore, students – especially those at universities – are disproportionately from the middle classes and above. Data show that they can expect to earn higher than average incomes over their lifetimes. Targeting support and assistance to the relatively small number of people who really do face barriers to higher education is very difficult. And it attracts fewer headlines than a commitment to pay large amounts to people who don’t need it, apparently so that they do what they always intended to do and would have done anyway. An untargeted fees-free policy amounts to a regressive policy, a policy that favours those destined to be better off at the expense of the poor.

Why do I say that? Because in New Zealand, as elsewhere, most social-policy spending such as welfare benefits is directed towards people at the lower end of the income spectrum. Even in health (where the entitlement to benefits is only very crudely targeted), such spending is skewed towards those at the lower end of the income scale. This is because low-income families are entitled to free doctor visits, are less likely to have health insurance (and so less able to access private healthcare) and are, statistically, more likely to experience very poor health that requires hospitalisation.

According to an article from Victoria University of Wellington’s Policy Quarterly, written by staff of the New Zealand Treasury, households in the top five income deciles receive 56-58 per cent of all government tertiary education expenditure – that is, more than a population-based share. Moreover, that analysis looks at all post-secondary education expenditure, not just higher education. Upper levels of tertiary education are likely to be more heavily skewed towards upper-income households. And, given that nearly 60 per cent of the fees-free beneficiaries were in degree-level qualifications, the policy probably enhanced the benefit to those in the upper-income deciles.

Furthermore, the Treasury analysis looks only at the decile status of the households from which students come. What’s more important is that their education means that they are more likely to be in the upper levels of income earners themselves once they start to make progress in their careers – the employment outcomes data make that clear – while those who don’t receive that support are likely to end up with lower earnings.

If the money wasn’t spent on the fees-free policy, it might join the pot for other social-sector spending, and so be distributed in ways that advantage lower household income deciles, or it might remain unspent – meaning that all taxpayers would benefit from reduced government debt (and reduced interest payments).

OUSA’s Bonnie Harrison states that tertiary education is a “public good” and that’s certainly true; research shows that societies benefit from a more highly skilled population. But completing higher levels of education also carries significant private benefits – higher incomes, wider career opportunities and a likelihood of greater well-being. That isn’t to say that governments shouldn’t subsidise higher education. If there was no subsidy at all for higher education, then there would be a lower demand for higher education than the economy needs (and, consequently, under-supply of higher education). But shared benefits argue for a sharing of costs.

Of course, a promise to reduce or eliminate higher education fees is politically attractive at election time. And not simply because it will appeal to the student vote. Rather, it plays on the anxieties of parents and grandparents who are concerned at the levels of debt that their children and grandchildren face. The British Labour Party’s 2017 promise to abolish higher education fees probably didn’t win it many more student votes, but it may well have been effective in persuading middle-class parents and grandparents to shift their allegiance.

We can look forward to an interesting debate on higher education fees in both the UK and US. But remember that a party promising to remove fees hasn’t seriously considered how to address the problems of access to higher education; rather, it’s marketing itself to the self-interest of the middle classes.

Roger Smyth, a former head of tertiary education policy in New Zealand’s Ministry of Education, now works as an independent consultant and adviser on tertiary education.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Cutting fees will not improve access

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login