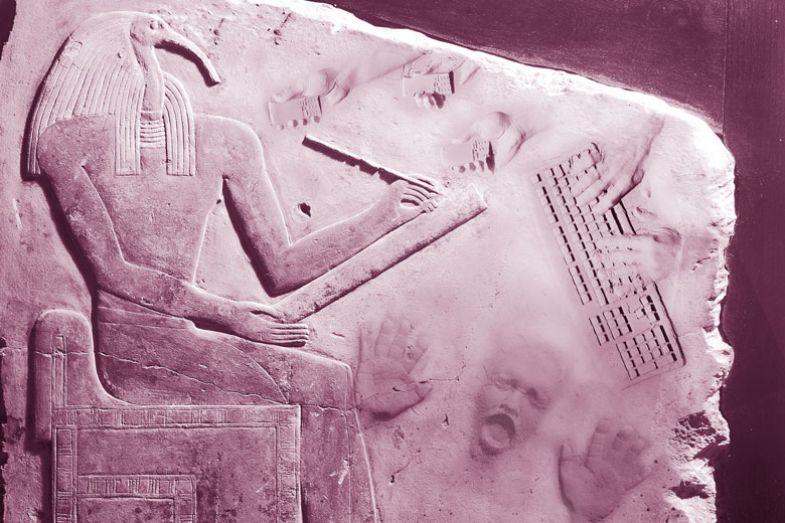

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates tells a story about the Egyptian god Thoth, whose inventions include writing. Socrates relates how Theban king Thamus warned the god that his discovery would “create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls”.

“They will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing,” Socrates recounts, in a translation by Oxford scholar Benjamin Jowett. “They will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

The passage could be taken as evidence of Phillip Dawson’s assertion that “panics” about new technologies and their impacts on learning date back two-and-a-half millennia. Sometimes there is good reason for concern, according to Dawson, associate director of the Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning at Deakin University. For instance, “the rise of the World Wide Web in the late 1990s was associated with a rise in copy-paste plagiarism,” he notes in his recent book, Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World.

THE Campus opinion: AI has been trumpeted as our saviour, but it’s complicated

Warnings about unintended consequences for students and their skills also accompanied the emergence of personal computers and word processors in the late 1970s, as well as pocket electronic calculators in the early 1970s and – presumably – the printing press back in 1444. And now, as technology powered by artificial intelligence (AI) becomes ubiquitous, the debate has returned for another round.

Those charged with enforcing academic integrity are already struggling to keep up with advancing technology. Recently emerged bugbears include various kinds of “word spinners” that help students disguise plagiarised work by changing some of the words and phrases. Tomáš Foltýnek, a semantic analysis expert at Mendel University in the Czech Republic, says detecting plagiarism that has been disguised through the use of such automated paraphrasing tools is “incredibly computationally hard” – particularly when suspect passages needed to be cross-checked against the “petabytes of database” held by companies like Turnitin.

But now educators are confronting the prospect of an even greater emerging challenge: whole original essays generated by AI.

“These tools are getting better and better. It will be more and more difficult to identify plagiarism or any other kind of cheating where students have not produced work that they submit,” says Foltýnek.

Even Turnitin is still in the early stages of addressing the threat. Valerie Schreiner, the company’s US-based chief product officer, says Turnitin has hired “leading natural language processing analysts” to “address some of these evolving edges of academic integrity”. She points out that AI can potentially be a great boon to assessment by saving markers from tedious and repetitive labour. For instance, Turnitin’s “AI Assistance” tool offers “suggested answer groups” for questions requiring one-line textual or mathematical answers, allowing academics to mark and give feedback to everyone who gave a similar answer simultaneously.

Schreiner also notes that the company uses AI extensively to defend academic integrity. For instance, one of its products uses AI to look for similarities in the code submitted in computer science assignments. “It has to be a little more sophisticated than text similarity [detectors] because it needs to look at structure and not just code words or text,” she says. “A student might change the variable names in a program, for example, in hopes of not being detected. AI is also used to look at any sorts of irregularities in student writing, like changes in spelling patterns, for indicators that the student hasn’t done the work.”

But some observers suggest that fighting tech with tech is only part of what is needed. The difficulty of detecting cheating “only underlines the importance of education, as such – universities and teachers should not rely on these technological tools”, Foltýnek says. “They need to work more closely with students.”

That sentiment is endorsed by Jesse Stommel, a digital studies expert at the University of Mary Washington in Virginia. He says that the concept of cheating is a “red herring” in discussions about technology and plagiarism: “What we need to do is build positive relationships with students where we can have smart conversations with them about their work, about citation, about what plagiarism is and what plagiarism looks like,” he says. “Ultimately, all of these companies – the cheating tech and the anti-cheating tech – frustrate those positive relationships.”

Part of the challenge, says Deakin’s Dawson, is to avoid sclerotic thinking around what assessment should look like. “We need to have a good argument about each new class of tools as they come along,” he says. But the debate should not be dominated by what he terms “assessment conservatism”: the idea that “we need to cling on to the types of things that we used to do” because of “familiarity or trust in old practices”.

He says academics need to consider how AI will influence the concept of “authentic assessment”, whereby students are allowed to use “real world” tools in assessment exercises. “We might want to think: what is a professional going to have access to in the future?” he says. “It’s about preparing students for the world that they’re going to be in – not just now, but into the future. If we don’t give students the opportunity to decide when it’s appropriate to use these tools or not, and to make best use of them, we’re not really giving them the sort of education they’re going to need.”

Andrew Grauer, CEO and co-founder of online study platform Course Hero, says that the increasing number of mature students at universities only sharpens the imperative to replicate real-world conditions in assessments. Students, like professionals, are looking for ways to get things done more efficiently and quickly – to “learn the most, the fastest, the best, the most affordably”, he says.

“I’ve got a blinking cursor on my word processor. What a stressful, inefficient state to be in!” he says. Instead, he could use an AI bot to “come up with some kind of thesis statement; generate some target topic sentences; [weigh up] evidence for a pro and counter-argument. Eventually, I’m getting down to grammar checking. I could start to facilitate my argumentative paper.”

Lucinda McKnight, a senior lecturer in pedagogy and curriculum who teaches pre-service English teachers at Deakin, agrees with Dawson that “moral panics about the loss of skills” accompany every new technological revolution. She also concurs regarding the perils of focusing purely on the negatives. “These new technologies have enormous capability for good and bad,” she says.

For her part, she has been experimenting with AI writers to “see what they could do” – and to gauge how she should adjust her own instruction accordingly.

“How do we prepare teachers to teach the writers of the future when we’ve got this enormous fourth industrial revolution happening out there that schools – and even, to some extent, universities – seem quite insulated from?” McKnight asks. “I was just astonished that there was such an enormous gap between [universities’] concept of digital writing in education and what’s actually happening out there in industry, in journalism, business reports, blog posts – all kinds of web content. AI is taking over in those areas.”

McKnight says AI has “tremendous capacity to augment human capabilities – writing in multiple languages; writing search engine-optimised text really fast; doing all sorts of things that humans would take much longer to do and could not do as thoroughly. It’s a whole new frontier of things to discover.”

Moreover, that future is already arriving. “There are really exciting things that people are already doing with AI in creative fields, in literature, in art,” she says. “Human beings [are] so curious: we will exploit these things and explore them for their potential. The question for us as educators is how we are going to support students to use AI in strategic and effective ways, to be better writers.”

And while the plagiarism detection companies are looking for more sophisticated ways to “catch” erring students, she believes that they are also interested in supporting a culture of academic integrity. “That’s what we’re all interested in,” she says. “Just like calculators, just like spell check, just like grammar check, this [technology] will become naturalised in the practice of writing…We need to think more strategically about the future of writing as working collaboratively with AI – not a sort of witch-hunt, punishing people for using it.”

Schreiner says Turnitin is now using AI to give students direct feedback through a tool called “Draft Coach”, which helps them avoid unintentional plagiarism. “‘You have an uncited section of your paper. You need to fix it up before you turn it in as a final submission. You have too much similarity [with a] piece on Wikipedia.’ That type of similarity detection and citation assistance leverages AI directly on behalf of the student,” she says.

But the drawing of lines is only going to get more difficult, she adds: “It will always be wrong to pay someone to write your essay. But [with] AI-written materials, I think there’s a little more greyness. At what point or at what levels of education does using AI tools to help with your writing become more analogous to the use of a calculator? We don’t allow grade-three students to use a calculator on their math exam, because it would mean they don’t know how to do those fundamental calculations that we think are important. But we let calculus students use a calculator because they’re presumed to know how to do those basic math things.”

Schreiner says it is up to the academic community, rather than tech firms, to determine when students’ use of AI tools is appropriate. Such use may be permissible if the rules explicitly allow for it, or if students acknowledge it.

That question of crediting AI is a “really interesting” one, says Course Hero’s Grauer. While attribution is essential whenever someone quotes or paraphrases someone else’s work, the distinction becomes less clear cut for work produced by AI because there are various ways that the AI might be producing the content. One rule of thumb to help students navigate this “grey area”, he says, is whether the tool merely supplies answers or also explains how to arrive at them.

More broadly, he says rules around the acceptable use and acknowledgement of AI should be set by lecturers, deans or entire universities in a way that suits their particular “learning objectives” – and those rules should be expressed clearly in syllabi, honour codes and the like.

Schreiner expects such standards to evolve over time, just as citation standards have evolved for traditional student assignments and research publications; “In the meantime, we need to support what our institutional customers ask us to,” she says.

For Dawson, the extent of acceptable “cognitive offloading” – the use of tools to reduce the mental demands of tasks – needs to be more rigorously thought through by universities. “I don’t think we do that well enough at the moment,” he says.

Laborious skills like long division, for example, are “somewhat useless” for students and workers alike because calculators are “the better choice”, he says. But in some cases, it could simply be too risky to assume that cognitive offloading will always be feasible, and educational courses must reflect that. “If you’re training pilots, you want them to be able to fly the plane when all the instruments work, and you want them to be able to make effective use of them all. And you want them to be able to fly the plane in the case of instrument failure.”

Indeed, for all their potential, AI tools carry considerable risks of causing harm – in education and more broadly.

McKnight cites US research into the use of AI in the assessment of student writing. “The algorithms make judgements that mean students who are outliers – doing something a bit different from usual, or whose language isn’t mainstream – are really penalised. We need to be very aware of how [AI tools] can function [in] enacting prejudice.” And the potential for AI to replicate biases and hate speech – demonstrated in the racist tweets of Microsoft’s Tay “chatbot” in 2016 – suggest that such issues could assume a legal dimension.

“If a bot is breaking the law, who is responsible? The company that created the bot? The people who selected the material that the bot was trained on? That is going to be a huge area for law to address in the future. It’s one that…teachers and kids are going to have to think about as well,” McKnight says.

AI also raises equity issues. Dawson draws a distinction between technologies owned by institutions – learning management systems, remote proctored exams and so on – and “student-led” use of AI. “Equity becomes even more of an issue there,” he says. “Some of it is going to be pay-for stuff that not everyone can afford.”

But the counter-argument is that AI improves equity because AI tutors are cheaper than human ones. That point is pressed by Damir Sabol, founder of the Photomath app, which uses machine learning to solve mathematical problems scanned by students’ smartphones, giving them step-by-step instructions to help them understand and master the concepts. “There are clear disparities between families that can afford a [human] tutor and those that can’t,” Sabol said in a recent press release.

AI offers the potential to make students better learners, too, according to Grauer. For instance, online maths tools such as graphing calculators and solvers provide step-by-step explanations as well as solutions: “It’s the exercising of questions, explanations and then more questions, like a conversation. When one wants to be doing enquiry-based learning, getting access to a…helpful, accurate answer and explanation is super powerful as a starting point. If one can string that together to a full learning process, that starts to get even better.”

But McKnight is doubtful that tech can effectively level the playing field. “What if the elite had access to human tutors who were personable and friendly and had emotional connection with you and could support you in all sorts of ways that the bots couldn’t, while lower socio-economic background students were relegated to getting the AI bots?” she asks. “As we know, with technology the reality doesn’t always fulfil the dream.”

Mary Washington’s Stommel warns that the technology could play out in very disturbing ways, as plagiarism detection companies harness data to “automate a lot of the work of pedagogy”.

“They have data about student writing,” he says. “They have data about how student writing changes over time because they have multiple submissions over the course of a career from an individual student. They have data where they can compare students against one another and compare students at different institutions.”

The next step, Stommel argues, is the development of an algorithm that can capture “who my students are, how they grow, if they’re likely to cheat. It’s like some dystopic future that is scarily plausible, where instead of catching cheaters, you are suddenly trying to catch the idea of cheating. What if we just created an algorithm that can predict when and how and where students might plagiarise, and we intercede before they do it? If you’ve seen Minority Report or read Nineteen Eighty-Four or watched Metropolis, you can see the dystopic place that this will ultimately go.”

Perhaps equally disturbing is the idea of a robot that is capable of enrolling in a university and taking classes in the same way as humans, ultimately earning its own degree – a concept proposed in 2012 by AI researcher Ben Goertzel, with his “Robot College Student test”.

This concept has recently come closer to realisation with news that an AI-powered virtual student developed by China’s Tsinghua University has enrolled on the university’s computer science degree. Such technology could amount to “a cheating machine”, Dawson says. Moreover, its arrival would raise the question of “what is left for people to do?” The answer, he says, is for students to be taught “evaluative judgement”: an “understanding of what quality work looks like”.

McKnight agrees that AI requires students to move beyond “formulaic” types of writing which “computers can do in a second” and develop evaluative judgements about difference.

“Say they get three different AI versions of something they want to write. How are they going to decide which to go with?” she asks. “How are they going to critically look at the language that’s used in each? They might take bits from one and merge them with bits from another. Editing will become much, much more important in writing. It’s a really exciting time.”

More broadly, Course Hero’s Grauer says educators need to “leverage what humans are best at doing. Computers can process information better and faster, store information better and faster, potentially even recall that information better and faster. But they can’t necessarily connect information as well.”

If questions around appropriate learning objectives and assessment standards are difficult to grapple with now, how much more difficult will they get as technology progresses even further? A 2012-13 University of Oxford survey found that AI experts rated the prospects of developing “high-level machine intelligence” by the 2040s as 50:50, rising to 90:10 by 2075. “That really changes assessment,” Dawson says.

McKnight predicts that the next advancement will be an “extension” of the current AI revolution. “But it’s going to be personalised, at scale, such that you’re writing with a bot beside you – a writing coach bot doing all sorts of work for you: researching, suggesting grammatical changes, edits, improving things, talking about ways to do things. So you are genuinely collaborating with this bot as you’re writing. Kids will be taught like this; everyone in industry will be writing like this; it will just be the way.”

Indeed, perhaps academics themselves will be writing and teaching alongside their own personalised bots – raising all sorts of further questions about what counts as originality and genuine insight. But what seems clear is that we need to start addressing such questions sooner rather than later, before this looming future is fully upon us.

“It’s what I’d call post-human – the gap between human and machine is dissolved,” McKnight says. “I don’t think it’s that far away.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login