This September, hundreds of outraged students in the Indian state of Punjab took to the streets in a demonstration that would result in the week-long closure of a university.

A female student had allegedly filmed other female classmates bathing in campus dorms at Chandigarh University, a private institution on the border of Haryana and Punjab states. The student later shared the clips with her boyfriend and another man, who were said to have posted the footage online. As rumours escalated on social media (including that some of the women filmed had killed themselves) and the alleged perpetrators were arrested, administrators issued firm denials, saying that they had found no evidence of videos taken without consent.

But the response prompted a huge backlash. “Instead of trying to assure us of our safety, the administration has been busy trying to salvage its image by denying anything happened,” one student told the BBC.

Whatever the truth of the incident, the emotion that it generates underlines what a sensitive subject sexual harassment and related issues have become in India. In another example from a month later, a video went viral showing male students scaling the gates and walls of a women’s college at the prestigious University of Delhi. Students later claimed the men cat-called and groped them, according to local media.

While sexual harassment is a global phenomenon, many academics say it is particularly pronounced in India, with the regular headline-grabbing incidents being just the tip of the iceberg of a problem that university administrations often fail to deal with adequately. Speaking on condition of anonymity, numerous scholars told Times Higher Education about instances in which institutions failed to protect victims and let perpetrators off the hook.

At one prominent Indian university, for instance, an older male scholar with a history of inappropriate behaviour took a female student to dinner, got drunk and started getting physical, despite her requests for him to stop. As one academic described it, “The fact of life is that everyone knows about him and has kept quiet about it, so he has continued.”

Elsewhere, a female faculty member reported a male student who had drawn a nude caricature of her while she was teaching. The student was suspended, but the academic continued to receive unwanted attention. Later that year, she received comments from a male colleague about her looks. When she made an official complaint, her vice-chancellor called her into his office and berated her and demanded to know what she was doing to make all the men look at her.

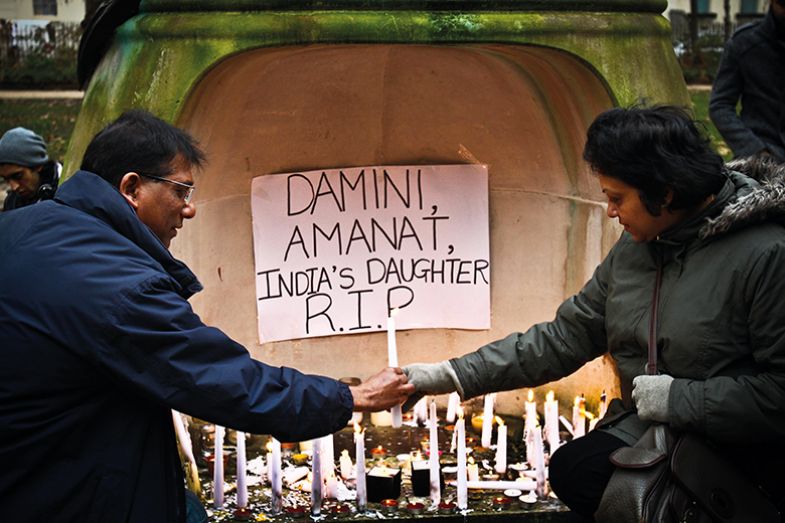

It is important, however, to see the incidents at Indian universities in their wider social context. In recent years, the country has gained something of an international reputation for poor treatment of women. In 2012, both the nation and the wider world were horrified by the gang rape and vicious assault of a physiotherapy student on a moving bus by six men. The student later died in hospital and four of the six men were sentenced to death – an unusual punishment in India. The following year, a 20-year-old college student was abducted, gang raped and murdered in Kamduni, a village not far from Kolkata. In 2020, the country was scandalised again when a 19-year-old Dalit woman was gang raped by four upper-caste men; she too later died. And, last November, further negative headlines were generated by the freeing of three men previously sentenced to death for the brutal gang rape and murder of another young woman in 2012, on the grounds that the evidence against them was unreliable.

Statistics suggest that crimes against women are rising in India, while one in three women in the country is likely to have been subjected to physical, emotional or sexual violence by their partner, according to recent research.

No national figures exist for cases of sexual harassment in higher education. Some academics who spoke to THE note that reported cases have gone up in recent years but that this does not necessarily mean that actual instances are increasing. Nevertheless, such a climate around gender relations clearly presents obstacles to universities’ ambitions to tackle the issue.

Many observers trace the problem back to centuries-old power imbalances baked into both India’s caste system and its patriarchal social structure, whereby higher-caste males can acquire a sense of entitlement to lower-caste women in particular. Moreover, until just a couple of decades ago, women were not well represented in academia, with few travelling far from home to study in big cities and live independently in dormitories. The separation of genders from early childhood, maintained right through the school system, may also bear part of the blame, observers suggest.

But whatever the reason, it is clear that universities cannot just wash their hands of the issue. According to the law, Indian employers in general are required to have in place protections against sexual harassment, and there are particular rules for higher education institutions. In 2013, India passed the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH) Act, making it mandatory for employers to protect women from sexual harassment in the workplace and to allow them to seek redress for grievances.

In India – as in neighbouring Sri Lanka and Pakistan – universities are also required to conduct training sessions for both students and faculty educating them on the issue. The government mandates that each university have in place a “gender cell”, made up of faculty and staff, to adjudicate on incidents of harassment and suggest appropriate punishments to university leaders.

However, the effectiveness of both training courses and complaints bodies is hit and miss, academics say. “Sometimes you lodge a complaint and years pass by without any action,” says Chani Vasana Imbulgoda, a doctoral researcher in higher education quality assurance at Sri Lanka’s University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

While some universities have “student counsellors” – lecturers meant to support students with problems, including harassment – they aren’t always equipped with the knowledge to tackle harassment. There are similar knowledge gaps among faculty tasked with running gender cells.

“We have to select persons with the capacity and interest and inspiration to do something,” says Imbulgoda. “Even with committees on this, there are serious questions about their calibre, their desire to reach out to students and their ability to think out of the box.”

In some cases, administrators actively try to sweep the issue of sexual harassment under the rug. A recent conversation with an administrator from another university was telling, says Imbulgoda. “She was reluctant to even talk about it. Lecturers feel that if they reveal the reality, that could bring some sort of bad image to the university.”

As much as reputation is a concern for universities, it is even more of a worry for victims of sexual harassment. Anamika Sinha, a professor at the Goa Institute of Management, who has served on bodies handling complaints of sexual harassment, notes the devastating effects of gaslighting on victims of harassment or gender-based violence.

“Many women do not really have the strength to lodge the complaint – both men and women gang up against the woman and no one stands up for her. Emotionally, that is difficult,” says Sinha.

Victims fear retribution. They also worry that reporting harassment will set them back in their careers – or they won’t be taken seriously. Even when good conditions are in place at universities, a “shame culture” is widely believed to prevent many of them from reporting incidents.

This is also true in Pakistan, says Mehvish Riaz, an assistant professor at the University of Engineering and Technology Lahore and a Fulbright fellow.

“In the Pakistani context, honour is an important factor that determines social relations,” she says. “Therefore, when women are harassed, they usually don’t raise [their] voices because it will damage their reputations. They will be victim-blamed, or the aggressor will take revenge.” Nor is seeking legal recourse an attractive option, Riaz adds, noting that Pakistan’s legal system isn’t seen as providing reliable outcomes.

Rules on harassment “have been clearly defined”, and committees have been set up to act on reports of incidents. “However, the dynamics of harassment are such that the girls get stuck in situations where speaking up, standing up for oneself or saying no is equivalent to loss [of reputation], marks, degree, job,” Riaz says.

Particularly tricky to handle are cases where approaches were initially favourably received. “Sometimes [women] consider it love, but later get disillusioned,” Riaz says. “Other times, those [harassing] men are in power, so those girls do not dare speak.”

In an article she co-authored for THE in 2018, Riaz wrote about relationships that form between Pakistani lecturers and students, who are often similar in age. Bans on such relationships are very rare in the region, although they are often frowned upon and considered a corruption of the student-teacher relationship.

“The situation becomes particularly fraught when the teacher’s advances are unwanted,” Riaz explained in her article. “Pakistan has had anti-harassment laws since 2010, but it is very rare for students of either sex to report advances from their teachers.”

Still, such relationships are fairly rare in the grand scheme of things, says Tanveer Hussain, rector of the National Textile University in Pakistan. While he acknowledges that the situation in Pakistan is far from ideal, he believes that sexual harassment is far less prevalent in his country than in India – something he puts down to the different cultural and religious environments.

Hussain’s own institution does not have mandatory anti-harassment training, instead favouring informal campaigns to raise awareness. A full-time female adviser is also available to students. He believes that sensible guidelines can help prevent situations in which harassment takes place.

“There are certain norms at universities. If you’re a female student, you’re usually advised not to go into a male teacher’s office alone but with a friend – and teachers are advised to not have students in their offices alone,” he says.

But institutions must not shy away from punishing perpetrators, Hussain believes. He recalls one incident in which a female student received inappropriate text messages from a teacher. The administration reacted swiftly. “Luckily, the teacher was just doing an ad hoc, temporary job, so we just shortened his contract,” Hussain says.

Part of the solution to tackling sexual harassment is raising awareness about its seriousness. But that has to be handled sensitively. While the victims include both women and men, there is a tendency in India to see prevention efforts as “anti-men”, says Sinha.

“At this stage, the tendency among faculty bodies is to see it as a women’s issue. But students are now beginning to get sensitised that it’s a social issue,” she adds.

An assistant professor at a well-known management institute in India, who requested anonymity due to concerns over discrimination and who we will call Sanjay, is among the younger male academics who aim to ally with women in the fight against harassment. But he says that to recruit more men to the cause, harassment training needs to avoid being too overbearing, inadvertently putting men in the shoes of perpetrators.

“A lot of times we get stuck because a lot of male faculty are hostile to such conversations,” he says. “If they become resentful and distant by imagining they could be the next target [of accusations], that makes it more unlikely we can get them on board.” Instead, men need to be encouraged to envision themselves as a colleague or friend of someone who has been harassed, or even as a bystander who wants to help.

He acknowledges that extending help is not always straightforward, particularly when the victim is wary of coming forward. “As a professor, it becomes very difficult when you only know from second- or third-hand sources that a particular student is feeling harassed…You may want to provide some kind of help, but they’re trying not to reveal their identity – for very good reasons.”

There are also times when he has witnessed inappropriate behaviour in all-male company. In such instances, he uses humour to gently question colleagues’ views – but he recognises not everyone finds it easy to broach the topic.

Moreover, while many academics – particularly younger ones – are well aware of sexual harassment’s insidious effects on victims, there are those who may not consider it a big issue, Sanjay says. “Older, upper-caste men are structurally privileged, so they have a lot more impunity and less desire to change sexist understandings or behaviour,” he says.

To head off sexual harassment among students, meanwhile, training is important, he believes. But it must be regularly repeated. Freshmen in India typically do a session on sexual harassment during their first weeks of university, but that is a time when they are deluged with new information, raising the risk that the seriousness of the issue does not sink in. “We need to probably have these trainings every six months at least,” he says.

Another approach that Sanjay has adopted is to embed sexual harassment awareness into mainstream curricula. In his experience, “for a lot of students, it’s the first conversation that addresses sexual harassment in detail”.

Institutions also need to get serious about their human resources policies. THE was told of at least two institutional leaders who were accused of sexual harassment but remain in post because the accusations could not be proved, forcing the women who accused them to leave instead.

But when people are fired, it is also important that their history of offending does not disappear from their record, potentially allowing them to reoffend at a new institution. This requires any university that might subsequently hire them to check out their background. Several academics told THE of instances when universities failed to do this. In one case, an institution recruited a professor who had been charged in a sexual harassment case. In other instances, universities lured by the star power of a highly cited professor have willingly turned a blind eye to their reputation for bad behaviour, scholars say.

While universities have different approaches to the problem, observers agree that the ones most effectively tackling the issue are those that have worked to gain students’ trust. “People don’t want to come out in public in cultures like ours,” says Hussain. “The only solution is to increase awareness as much as possible and give students the confidence that their case will be heard in total confidence.”

On the flip side, academics say that protections and formal processes also need to be in place to ensure that those accused of wrongdoing aren’t scapegoated and that they receive a fair hearing.

“When we’re dealing with sexual harassment cases, we have to listen to both parties: the so-called perpetrator and victim,” says Imbulgoda. “Sometimes it can be the other way around: the person who is depicted as the predator can be the victim.”

She cites the cautionary tale of one young male lecturer who was forced to resign without so much as a trial because a female student claimed he had touched her backside.

Fixing the problem also means instilling confidence in students to stand up to harassers, Imbulgoda believes. “We can have all these structures, committees, awareness trainings and counselling – but all these are peripheral things. The core way of wiping out sexual harassment is to better equip the person,” she says.

And while university administrators need to be proactive, they must also be patient, understanding that there aren’t any quick fixes.

“When you talk about social change, the process has to be slow, otherwise the backlash will be so strong that the process just won’t pick up,” says Sinha. “For some time, there was #MeToo, but then it fizzled out. The way forward is for those of us who have been through [harassment] or understand it to not give up and continue the conversation.”

She is doubtful that those seeking to fix the problem will succeed in winning over individuals who harbour deep-set patriarchal beliefs, but she doesn’t despair.

“There are those that we will probably never change,” she says. “But changing them may not be required. Once they are in the minority, things will improve for women despite them.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login