The cringe factor

An awful lot of my own pedagogical praxis is informed by negative example, framed by two questions: “What was learning like when I was an undergraduate?” and “How can I make it better for my own students?”

The laissez-faire attitude of many of my lecturers was an inevitable consequence, perhaps, of doing a degree as the 1980s turned into the 1990s. These were relatively halcyon days to be a student (full grants, anyone?) but that doesn’t mean everything was better.

I vividly recall philosophy seminars where 15 or more of the 20 or so of those present would chain-smoke roll-ups, no doubt imagining themselves on the Rive Gauche. In those days, “health and safety” meant ensuring your cigarette was completely extinguished by the end of the lecture or seminar, and “learning resources” were chemical-smelling, lopsided, handwritten photocopies, the content sometimes having half slid off the page. There was nothing unusual in waiting for a seminar to begin, and then decamping to the coffee bar instead because the lecturer was a no-show. Very, very few of the lecturers were qualified teachers, either. But many were inspirational nonetheless.

When I started lecturing, I was encouraged to get a teaching qualification. I found the process fairly dry and detached from my actual classroom experiences – though, 20 years later, I can still quote a piece of pedagogic research I read about the alignment of teaching, learning and assessment! What the PGCert gave me more than anything was a sense of being a “proper”, reflective teacher, of the sort so few of my own lecturers had been.

THE Campus views: How I stopped worrying and learned to embrace pre-prepared courses

My certificate really should have come with a minor in Cringe, however. It’s something I’ve excelled in over the years. It took me an inordinately long time to realise that being “down with the kids” is rarely advisable and almost never successful – especially by people who use the expression “Down with the kids”. It would explain the tumbleweed moments – the blank faces whenever I share my thoughts on how, in his Daemonologie, James I had “Ninety-nine problems but a witch ain’t one”; the pitying looks at my objectively side-splitting “bashing the bishops” quip when teaching Milton’s antiprelatical tracts; and the near-universal incomprehension of students born well after Kurt Cobain’s death as I put up a slide – “Courtly Love: Poetic Nirvana?”.

There was also the lecture in the early, analogue 2000s where I chastised a group of Monday morning students for their tardiness, only for one of them gently to point out that I appeared to have altered my watch an entire week before the clocks actually changed. A few years later came the seminar where my repeated “Could whoever’s left their phone on please turn it off?” grew increasingly passive-aggressive-shouty-unamused until – of course you’re ahead of me – I realised it was my own.

It seems that there are some basic failings of human functionality for which no teaching certificate could ever compensate.

Emma Rees is professor of literature and gender studies at the University of Chester.

Signalling failure

As a member of a graduate student research department, my teaching loads are comparatively small. That said, I still have a litany of mea culpa experiences. Like the 11.45 phone call from a course coordinator asking when I might be expected to arrive for my noon class at the college nine Tube stops and a 25-minute jog from my office. Or a student politely pointing out 15 minutes into a lecture on advanced oncology that perhaps I wasn’t aware that this course was Introductory Cell Biology for Physicists. Or, more recently, realising during a Zoom lecture that my internet connection had frozen 15 slides earlier.

There’s not much to learn from these errors – except, perhaps, that Outlook alerts and frequent interaction with your audience are good practice. But I can recall two examples that were – to me, at least – “teachable moments”.

The first was one of my first-ever presentations. I was a biochemistry graduate student in Dundee and my supervisor had volunteered me to give a short talk at the Winter meeting of the Scottish Protein Group in Edinburgh (note: this group did not actually study proteins of Celtic heritage). This was in the early 1980s, before PowerPoint or even laser pointers. Slides had to be prepared by hand photography days in advance – and every one of mine had to be created from scratch.

The preparation done, a bunch of lab mates and I squeezed into a car and headed off to Edinburgh. I was relieved that my supervisor wasn’t driving, given his penchant for wrecking cars. But I should have paid more attention to what he was doing instead with my slide carousel.

It was only when I began my lecture that I realised he had not only rearranged my slides but had also added a few from his own collection. This was with the best intentions and significantly improved the logical flow. But it meant I had as much idea as the audience about what was to be projected next. Lesson: the cadence of a lecture is important for effective communication and requires not only comfort with the content but confidence in the sequence of its delivery. Be prepared!

My second teachable moment was more recent, from a lecture at a Lorne Conference in southern Australia. My research lab has worked for many years on pathways that control how cells respond to their environment. Understanding of these signalling systems has evolved from linear cascades to protein assemblies that form specialised nodes. However, textbooks still denote these systems as largely insulated from each other, delivering specific signals by virtue of their distinctive components. One of the proteins we work on is an integral component of many of these pathways, raising the question of how a cell can tell what the original signal was if the same protein is affected by many signals.

I attempted to introduce this conundrum with a slide that distilled all signalling systems down to a handful (of which the majority involved the promiscuous protein). Immediately, though, there were grumblings in the audience, which persisted into the Q&A session. What about pathway X, Y and Z asked the professors studying pathways X, Y and Z. They’d focused on the simplistic set-up and not the new supporting data.

I’d made two egregious mistakes. First, it is unwise to make a contentious or underdeveloped assumption at the beginning of a lecture. Build your evidence first. A footnote to the offending slides might also have helped – “Illustrative, not exhaustive”.

Second, it’s very easy to offend people who have invested their careers in areas you may have only scattered knowledge of. In academia, it is fine to question everything, but we all see the world from different perspectives. Hence, if you want to change people’s thinking, you need to be empathetic and respectful. Warm them up first – and pre-test assumptions on your close colleagues.

Jim Woodgett is senior scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Toronto, and president and scientific director of the Terry Fox Research Institute, Vancouver.

Prepared for the worst

It is late in the semester of my undergraduate seminar on medieval English literature, and no one will speak. I have done my usual warm-up, lecturing casually for 10 to 15 minutes on the sources and historical context for the day’s reading, pulling out a few key points, then throwing out a question to stimulate discussion. The question stimulates nothing. I rephrase it. Silence. I try a few other prompts on my list, some wide open, some more specific, hoping one of them will be the hook that grabs a student’s interest. Zip.

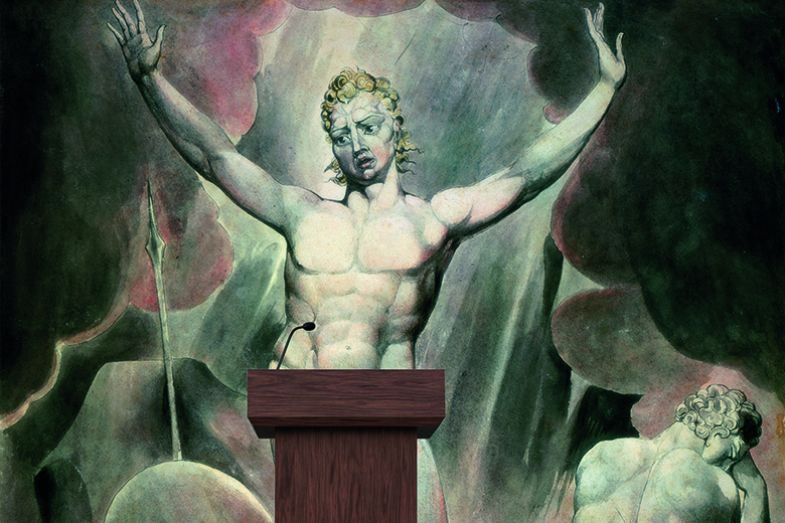

There is a scene in John Milton’s Paradise Lost in which Satan tells the fallen angels about the new world God has made, and asks them who is brave enough to go explore it. The devils fancy themselves epic heroes, so Satan looks around expecting a volunteer – “but all sat mute.” I cannot help but think that Milton knew the feeling of trying to lead a seminar discussion with unprepared students.

For, as it turns out, none of my students had done the reading. I was at a loss for how to proceed, until I remembered that a colleague once taught me a strategy for this precise situation. Calmly, without anger, I said, “I don’t know how to teach a class like this. Let’s meet again next time when you are better prepared.” Then I gathered my books and dry erase markers and left the room.

The next time we met, my students came ready with so many observations about the reading that I could barely get a word in edgeways.

I have been teaching literature at universities for 15 years, and until recently, I still felt a knot of pain in my stomach before heading to the classroom. For most of that time, I assumed it was stage fright, and that, like actors, I would have to put up with it for the rest of my career. Only recently did I begin to understand that I was not afraid of performing per se – giving a lecture arouses no anxiety. What worries me is the prospect of having to lead students in a thoughtful, coherent, enriching discussion, without knowing how many of them will be ready to speak.

I believe in the pedagogical value of the seminar, and don’t want to force students to be passive receptacles for my opinions. But the uncertainty takes its toll. In catastrophic scenarios, I can send everyone home, and that predictably improves their performance for the rest of the semester. But there are many so-so classes where it would be inappropriate.

Surprisingly, the pandemic helped me find a solution. After a disastrous first semester of online teaching, I decided to assume none of my students would be prepared, and I designed my classes accordingly. Instead of freeform discussion, we moved to extensive translation (from Old and Middle English) and close reading. I told students that I expected them to participate in class no matter what, and they did.

To my surprise, they also began talking more, noticing both fascinating details and larger patterns. The discussions I had previously struggled to bring about now arose organically. On low-energy days, we still had translation to fall back on. At one point I noticed that my stomach pain was gone, and that teaching left me energised rather than drained. Expecting the worst-case scenario and planning for it made teaching a reliable pleasure, and more productive for my students too.

Irina Dumitrescu is professor of English medieval studies at the University of Bonn.

Tunnel vision

Stepping up to the lectern one day, as a youngish lecturer, I was keen to provoke a reaction from what was a large audience. I was, I think, well organised, but I felt awful and it showed: my delivery lacked any kind of enthusiasm. I paused, not for dramatic effect, and a loud yawn filled the silence. Everyone laughed and even I managed a smile of sorts.

The only good thing about this wholly uninspired performance (which I probably shouldn’t have given in that condition) was that, in retrospect, it maintained a record from my first tutorial as a tutor in 1968 to the last lecture I ever gave in 2020, which was that I always turned up – however much the quality varied.

That chastening moment early in my career has, of course, stayed with me. But I soon realised that the other end of the spectrum – presiding over a class of over-stimulated students – is far more dangerous, albeit fairly interesting. One environmental politics course in the 1970s ended with two students facing off over my desk about climate change (yes, even then). The word “moron” was used repeatedly and reciprocally, along with other unsavoury adjectives, and they had to be prised apart. At least my seminars developed a reputation for being lively.

Slightly more extreme was the graduate seminar on nationalism in which a Greek student, responding to an entirely unintentional stimulus, rose to his feet trembling with rage and announced that if anyone else used the word “Macedonia” he would kill them. What better way for the polite Home Counties element in the audience to learn that the emotions generated by the signs and symbols of national identity could be a deal more powerful than was allowed for in their philosophy?

But the possibilities of disaster in the seminar room were as nothing compared with those of the minibus. I took students on more than 100 field trips during my career, nearly always acting as both lecturer and driver. On one journey between the Wirral model town of Port Sunlight and Liverpool, then wracked by urban decay, I briefly and erroneously imagined I was driving my own car and zoomed into the “cars only” lane of the Mersey Tunnel. The roof rack on the minibus totalled the overhead sign with an enormous bang. There were shrieks, followed by gales of nervous laughter from the students as I drove the, fortunately, undamaged vehicle over to where a uniformed official of the Mersey Tunnel Company was watching phlegmatically.

“What do you want me to do about this?” I asked. “What do I want you to do?” he replied in fluent Scouse. “I want you to fuck off or we’ll be filling in forms all day.” So I did – having provided students with arguably their most memorable slice of Merseyside culture that day.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick.

Class war

For many years, I assured myself that the low point in my university teaching had come very early in my academic career.

That apparent nadir happened not long after taking up a postdoctoral position at a post-92 institution in London where, holding a newly minted PhD, I was asked to teach a basic first-year module in social theory. Armed with a wodge of acetates and an overhead projector (this was long before Microsoft had invented PowerPoint), I would slowly take students through the classical canon of my discipline.

My neophyte enthusiasm for unpacking the basics of Max Weber and Emile Durkheim seemed to go down well with students, even if they weren’t always that attentive. But things took a different turn one morning during a lecture on Marx’s Hegelian-inspired theory of industrial capitalism. From the lecture auditorium came a series of interruptions, taunts and heckles – not from my students but from two young academics from my department who had taken it upon themselves to stand at the back of the lecture hall and give me real-time feedback in the form of these repeated jeers.

I later found out these two colleagues were firebrand Trotskyists and seemed offended by my overall analysis of Marx’s revolutionary historical materialism (I forgot to mention it). I become so exasperated at one point that I bellowed back to my radical detractors: “don’t blame me – blame the textbook”, for I had lifted much of the lecture content (even that of the whole module) from a single tome. One of my hecklers has since become a very respected and senior professor at an august university. In fact, I came across him at a conference back in 2013, where he was involved in a keynote session; I reined back the temptation to heckle.

Although at the time I was shaken by this attempted coup from within my own class, this episode and other early teaching fails prepared me to expect anything and everything, in the hope that the unexpected might never happen again. Except it did – when the pandemic arrived and remote teaching became the socially distanced norm in universities.

At first, using Zoom proved a novelty: you could, in theory, teach in your underwear anywhere in the world if you were allowed to travel and had enough money for a quarantine hotel stay. I even imagined remote teaching could start a pedagogical revolution in higher education – where lecturers become content creators and university learning platforms would morph into streamed services for asynchronous content – a University of Netflix.

Two years into this enforced experiment, I am suffering from real Zoom fatigue. On one occasion, so exasperated by the prospect of another wall of blank screens and silence, I went on a mildly profane rant thinking I was on mute. My mic had been on the whole time.

My excuse if students complained: I was heckling another lecturer.

Michael Marinetto is a senior lecturer in management at Cardiff University.

Course correction

In 2014, in just my third year as a faculty member, I was made course coordinator for a structural bioinformatics course. This was taught every year to our engineering students by multiple teachers – but I had not been among them.

Taking responsibility for an established multi-teacher course on which I had never taught was a rather odd position to be in, and I worried about how it would be received by the instructors and how much I would usefully have to offer. So when, within a few weeks, the students started complaining about the course material, my heart sank into my boots.

A number of meetings ensued between myself, student representatives and the course teachers. During these, I learned that this course had historically been one that the students were afraid of taking. One of the reasons they found it so challenging was that, as engineering students, this was the first time in their degree programme they were exposed to biology. The way biologists think about and approach problems was completely new to them.

Such interdisciplinary variations in approach are not something academics often think about when teaching students from distinct fields that are close to their own. However, I could see where the students were coming from. And, here, my lack of personal investment in the teaching of the course worked to my advantage, as it gave me the psychological licence to completely restructure it during my second year of managing the course – which was also my first year of teaching on it.

The redesign – which was strongly supported by my director of studies – included rewriting all the lecture material and redoing the lab compendium to include detailed background and instructions. The main changes I made included making sure there was structure and alignment between course content and learning objectives, improving the quality of visual aids, explaining to the students why they were learning certain things, and, above all, listening to them and taking their concerns into account. I was honest about prior challenges with the course and asked them for ongoing feedback, on the basis of which I continued to improve the course throughout the time I was responsible for it.

On the first day I taught the restructured course – in tandem with a colleague I enlisted, who is an excellent teacher – a student came up to me and told me they had been really scared of taking it. However, the horrors they had been told by previous students to expect had not materialised: they were really happy as they felt a totally different tone was being set. This made me optimistic for the semester ahead.

The experience highlighted how important honesty and open dialogue with students is if you want to maximise the quality of your teaching. This was particularly important for me to learn as I have subsequently gone on to teach students from a wide range of backgrounds and STEM disciplines. Completely overhauling the course was a major time investment, but it was incredibly gratifying as the course evaluations went from strength to strength.

By the end of my four years of responsibility for the course, I had managed to take it from being one that students were most afraid of to one they actually looked forward to taking. What I had initially seen as a big, unwanted challenge had become one of my biggest, proudest teaching successes.

Lynn Kamerlin is professor of structural biology at Uppsala University.

Ending in tears

Ahh! I screamed internally. Too shocked at what I was seeing to move, I wanted to yell out loud, but I was worried about making the two students in front of me jump. If either had moved, even slightly, one of them would almost certainly have been blinded.

I was a postdoc at a well-known university in the east of England and, like many early career academics, I supplemented my income and gained teaching experience by demonstrating in laboratory classes.

That day it was a biochemistry practical for medical students. It was based on lysozyme, a small, naturally occurring, antimicrobial compound found in body fluids such as tears and saliva. The idea was for the students to collect their sweat (by putting on several coats and running multiple times around the building) and tears (by using various lachrymatory, or tear-causing, agents such as onions) and to determine how much lysozyme was present in each.

The sweat and tears (yes – literally!) were supposed to be collected in small plastic tubes. This was clearly documented in the practical manual, which the students in front of me equally clearly hadn’t read. I watched incredulously, and with a growing sense of alarm, as one student carefully approached the other, arms raised, clearly intending to collect tears directly out of their fellow student’s eye with a glass pipette. The student hadn’t even picked up a small pipette, but one large enough to need two hands to hold.

I wasn’t sure who was more unwise; the student holding the pipette or the one allowing someone to come anywhere near their eyes with it.

After what seemed like an age – in reality, probably only a few seconds – I launched myself across the desk and yanked the pipette backwards out of the undergraduate’s hands. Only then did I let out my breath.

“Hey!” said the student. “What are you doing?”

“Saving your lab partner’s eyesight!” I responded. “What on earth were you thinking?”

“Well how was I supposed to collect the tears then?” came the somewhat indignant response.

To this day, the sight of that student approaching the eye of the other with a large, pointy piece of glass is the scariest thing I have ever seen in a lab (or any class). I’ve also seen students absentmindedly tap containers of toxic compounds against their teeth, spill radioactive dyes on their trousers, heat things in test tubes with the open end pointing at themselves, and purposely touch things they had just been told were extremely hot “just to check”. No students were ever harmed, however, and all these incidents, scary as they were, taught me valuable lessons.

First, you can’t plan for everything. The biochemistry class was well run, with clear instructions and detailed briefings for staff and students, yet the unexpected still happened. You always need to be adaptable and observant.

Second (and something that has served me well since), never assume students have read the instructions, or that they understood them. They aren’t experts and are still learning. Always check and clarify (multiple times).

Finally, even the best of us, however unintentionally, are capable of doing very, very silly things.

Oliver A.H. Jones is a professor of analytical chemistry and associate dean for biosciences and food technology at RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login