M. Brian Blake’s first taste of management came at an unusually young age, while working at his parents’ petrol station in Savannah, Georgia.

“I worked there, pumping gas most days after school from an early age, but started doing the accounts when I was 12,” explains Georgia State University’s first black president. When his father bought an Apple computer in the early 1980s, Blake digitised the accounting system and began writing his own code, including one to simplify inventory purchases. By the age of 33, that gift for programming had seen him become America’s youngest black professor of computer science.

Blake’s journey from the petrol station forecourt to the biggest office at Georgia State, a seven-campus research university with 51,000 students and a $1 billion (£800 million) annual turnover, is one of the most remarkable rises in US higher education. Although he is not the only university leader who was the first in his family to go to university, he is still unusual: a 2021 study found that 52 per cent of tenure-track faculty had at least one parent with a graduate degree and 22 per cent had one with a PhD. Blake’s father, by contrast, “started as a factory worker, then became a police officer before buying the gas station”.

Yet when Blake and his elder sister became the first in the family to attend university, his parents’ “incredible pride” further stoked his ambition. “I wasn’t an outstanding student,” he reflects. “I got mainly Bs in my first year. But I thought, ‘I need to take this further and get a PhD.’”

That didn’t happen immediately, however. After graduating from the Georgia Institute of Technology, he worked for six years at various software consultancy firms, including Lockheed Martin and the MITRE Corporation (“60-70 hours a week”), before doing a doctorate in software engineering at Georgetown University. There, he was recruited to teach and four years later was made a tenured professor: “I’d heard some people had got tenure in five years, so I aimed for four – maybe I was being a bit arrogant, but I achieved it,” he says.

With a background in overseeing projects, he was fast-tracked into departmental leadership roles and then promoted to dean, provost and vice-president roles at leading private universities, including the University of Miami, Drexel University and George Washington. At the age of 50, he took his first role at a public university when he became president of Georgia State in August 2021.

Blake is one of a handful of black academics who have recently been appointed to lead some of America’s top universities, including Harvard University’s Claudine Gay last year and the University of California’s Michael V. Drake in 2020. But it is arguable that Georgia State is even more socially important than these globally renowned institutions. One of 131 Tier 1 research institutions in the US, it has achieved the seemingly impossible in the past decade or so by boosting enrolment of lower-income students while simultaneously cutting dropout rates dramatically, often using low-cost interventions. As a result, Georgia State holds the distinction of graduating more black students than any other public university and is fourth for master’s degrees, winning praise from Barack Obama and Bill Gates among others.

This remarkable feat was detailed in the 2020 book Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (New Press) by British investigative journalist Andrew Gumbel. Its descriptions of how former president Mark Becker employed a data-led strategy to defy the odds has drawn comparisons with Moneyball, Michael Lewis’ 2003 book setting out how a similar approach led to the transformation of the Oakland A’s baseball team in the early 2000s.

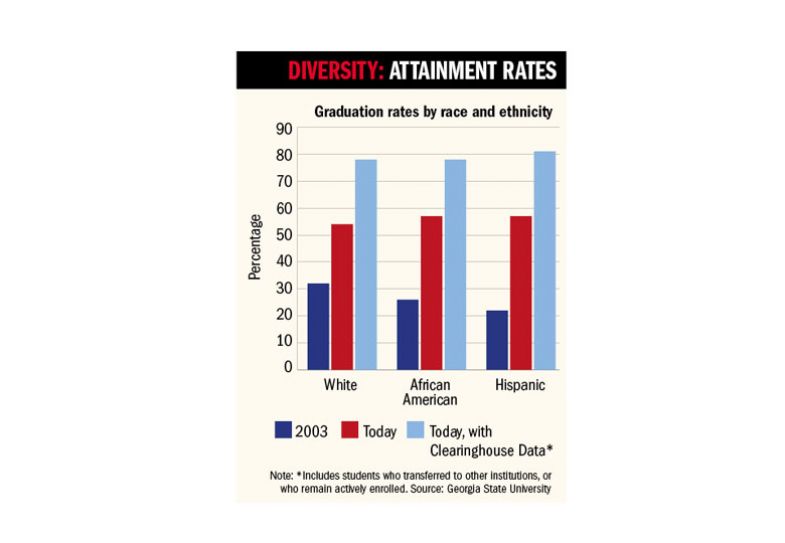

To illustrate the scale of the achievement, it is worth considering that in 2003, just 32 per cent of white students graduated from Georgia State, and attrition rates were even higher for minority students, with only 26 per cent of black and 22 per cent of Hispanic students graduating. Now, the six-year completion rates are closer to 60 per cent, and the rate rises to nearly 70 per cent if those who transfer and graduate from other institutions are included, as low-income and first-generation students are disproportionately likely to do. In addition, the race attainment gap – which, in 2003, saw Hispanics almost half as likely as whites to graduate and black students a quarter less likely – has been all but eliminated.

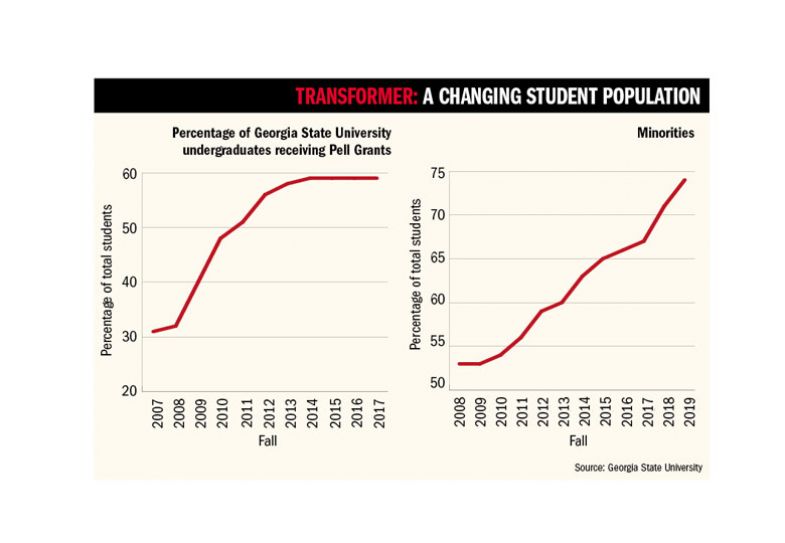

Remarkably, this has occurred while Georgia State has diversified its intake, with the proportion of the student body comprised of ethnic minority students increasing from 53 per cent in 2008 to 80 per cent in 2021. Significantly, many more students from lower-income families have been admitted over this period, with the proportion of undergraduates with Pell Grants increasing from 31 per cent in 2007 to 59 per cent by 2014.

Encountering this racial diversity daily is inspiring, says Blake. “These mixed groups of students working together is great – our environment looks like what America and the world will look like more and more over the next couple of decades...There isn’t a better place to educate the citizens of tomorrow.”

Knowing some of the financial hardships that students still face makes Blake more determined than ever to find ways to ease their journey. “I’ve experienced the whole spectrum [of economic status] because by the time I made it to college, my parents’ business had started to do quite well – I was driving a Porsche to school, so everyone thought I’d always had it easy,” he recalls. “But it wasn’t like that – we were definitely in the lowest income quartile for many years, so I’ve seen things from both sides.” And wealth unquestionably makes a difference to children’s chances, he believes: “Now, as a parent, I understand how important it is to read with your children, but both my parents worked full-time, so this was difficult for them.”

Finding ways to help financially disadvantaged students overcome the multitude of difficulties they face – academic, financial, social and administrative – has been part of Georgia State’s success. In 2015, 19 per cent of first-years who accepted a place, mostly non-white, failed to show up in the autumn. Identifying the hidden barriers to enrolment – such as difficulties in navigating financial aid applications, finding the right identity documents or obtaining required immunisation records – helped to cut the university’s so-called summer melt by 37 per cent, leading to an extra 365 students in class than before. As Blake notes, losing these students is bad for the university too, costing it about $3.2 million annually given that tuition fees are just under $10,000 a year.

Changing the structure of learning has also helped incoming students. They now join “Freshman Learning Communities”: study groups of 25 who take courses together. Among those courses is a non-credit-bearing unit introducing the basics of university life, including how to access careers services and pastoral support. That scheme has led students to swap their majors less often, while first-year visits to careers services have quadrupled. Since 2011, the number of STEM degrees awarded to black students has risen by 158 per cent on an enrolment increase of 50 per cent, while four times as many Hispanic students now graduate compared with a decade ago (enrolment doubled for this cohort in the same period).

Georgia State’s most important policy, many believe, is the Panther Retention Grant. Although student debt can seem crushingly huge, the university recognised that it was small unpaid dues that often prevented students from finishing their courses. In 2010-11, more than 1,000 Georgia State students were being dropped from their classes each semester for non-payment of tuition and other fees. From 2016, those deemed on track to succeed academically and with modest unpaid fees were offered the Panther micro-grants on condition that they meet a financial counsellor to plan their finances for the rest of their degrees. In the last academic year more than 2,000 grants – some as low as $300 – were offered, with 87 per cent of grantees graduating within a year.

Georgia State was also an early adopter of AI chatbots for engaging students. Although some dismiss AI as a gimmick or distraction, Gumbel detailed in Won’t Lose This Dream how the technology had life-changing effects for many Georgia State students. One low-income student who was repeatedly turned down for support was advised by the AI to approach the financial aid office; there, an administrative error with his social security number was quickly identified. Chatbots have also been widely adopted in recruitment; currently, Georgia State’s AI tech answers about 185,000 questions in a typical recruitment cycle.

Meanwhile, the university’s predictive learning analytics system, known as GSI Advising, tracks 30,000 students daily, sending out more than 800 types of alerts to those deemed at risk of failing. Last year, this led to an astonishing 55,000 meetings between students and advisers to discuss specific alerts and help get learning back on track.

Blake, a data analytics expert, is obviously excited about where technology might lead if it could be extended into teaching itself. “When I was helping my son with his algebra and was trying to get my head round it, I went on to the Khan Academy [a free education website] to see some of the lectures,” he reflects. “What if I could do a customised push to students after their tests, or as they’re studying, so they can get the pedagogic support they need in real time? If students embraced this, you can imagine how their aptitude would grow – there is this opportunity to have this hovering angel watching you. It could see how you’re doing work in the digital platform and make suggestions in real time – it could be a really cool technique to enhance learning.” Although he admits this kind of tracking can feel “creepy”, the benefits could be transformative, he believes.

Having spent a year interviewing students, staff and administrators at Georgia State, Gumbel thinks Blake’s optimism about the use of technology is justified. “It’s easy to...worry that machines will invade students’ privacy or write their essays for them – but the spectre of Big Brother coming to campus is almost always overblown because universities do not operate in the private commercial sphere and are bound by strict rules on what data they can collect and disseminate,” Gumbel tells Times Higher Education.

But neither should technology be seen as a silver bullet, he adds. “What matters more is a clear sense of mission. A university that doesn’t know how to look out for its students’ best interests can’t cover that deficiency with technology. But a university that wants to use machines to learn more about its students and understand and meet their needs can harness technological advances to powerful effect.”

That mission to support students will need to be balanced with Georgia State’s commitment to research, with Blake currently in the process of shaping Georgia State’s next 10-year strategic plan after the institution more than doubled its annual research income to $200 million in the decade to 2021. But attention to detail on why students stumble and fall throughout their studies – and how they can be helped – will remain central to Georgia State’s identity. As Gates noted in 2017, the university’s “key insight is that there isn’t a single big reason that leads to students dropping out. It’s dozens of smaller things that disrupt their journey to graduation.”

Given the scale of transformation achieved under Mark Becker, Blake has a tough act to follow. Yet the continued success of Georgia State matters because many regard its innovative support for undergraduates as a blueprint for what American universities can achieve when leadership, technology and collective effort are harnessed effectively. And it is not just the fortunes of the struggling US public higher education that the university's example could revive, some believe. If Georgia State can break the stubborn link between demographics and destiny then it will reawaken the American Dream.

A self-made computer whizzkid who has lived that dream himself sounds like just the person to lead that endeavour.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login