While most UK universities have increased the tuition fees they will charge international students next year, few have dared to increase them above the rate of inflation, new data reveals.

Experts said that institutions may have worried that trying to keep pace with inflation – currently nudging double figures in the UK and many other nations – would be a risky strategy in such a competitive market.

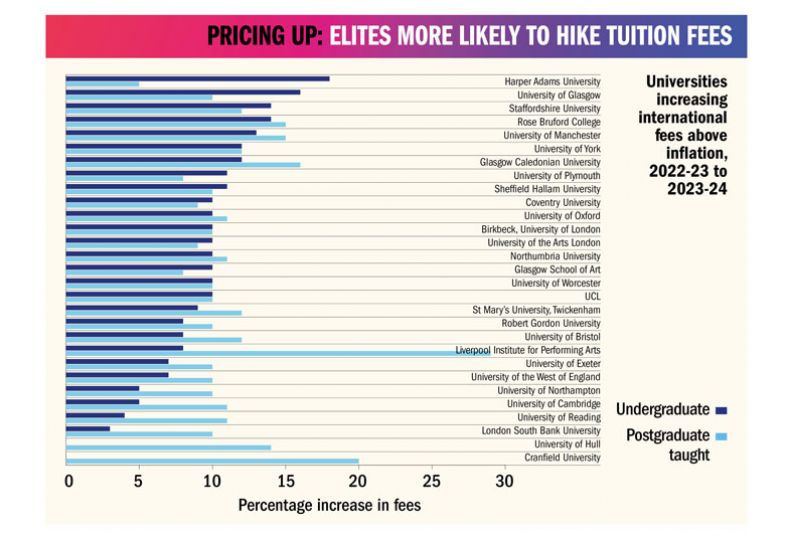

Figures from The Knowledge Partnership’s (TKP) Courses 360 database show that the majority of a sample of 154 public universities raised their full-time undergraduate international fees for 2023-24 entry, but only 18 (12 per cent) raised them by more than the average annual rate of inflation.

The data, which excludes medicine, dentistry and veterinary medicine courses, those taught at satellite campuses and those done jointly with another university overseas, also reveals that about half of institutions raised their fees by between 2 and 5 per cent.

Similarly, just 26 (16 per cent) of 159 institutions increased campus-based international fees for standard master’s courses by more than 8.8 per cent – the average rate of inflation for the 2022-23 financial year.

The average increase in postgraduate international fees per institution was 6 per cent, but was higher among institutions in the research-intensive Russell Group, which had an average rise of 8 per cent.

The postgraduate analysis excludes pre-registration health and architecture courses, law conversions, and dual degrees taught in partnership with overseas institutions.

Amy Ross, a senior consultant at TKP, which is a Times Higher Education company, said some universities may have set their 2023-24 fees before the unprecedented inflation rise.

Some may have been worried about pricing themselves out of competitive markets, and others may have placed greater value on widening access, she said.

“University finances have been stretched by the reducing value of home undergraduate fees, but at the same time the sector is increasingly reliant on tuition fee income,” she said.

“Inflation and the cost-of-living crisis will continue to add to the financial troubles felt by institutions, and there is no easy fix.”

Examining which institutions’ fee increases outstrip inflation adds some support to the notion that the most prestigious universities felt able to push their prices up the most. For example, the University of Manchester has increased its international undergraduate fees by 13 per cent, and its international postgraduate fees by 15 per cent.

For the University of Glasgow, the corresponding figures were 16 per cent and 10 per cent, while the University of York put up both sets of fees by 12 per cent.

However, increases of a similar scale were reported by less prestigious institutions, such as Glasgow Caledonian and Staffordshire universities. And some specialist institutions were among the biggest price-hikers, too.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, said the figures could be a lesson for politicians.

“If ministers are not willing to raise fees for home students from £9,250 in England and £9,000 in Wales, perhaps they should at least consider raising them by 6 per cent?” he suggested.

“The international student market is so competitive and UK inflation is so high that it would be risky indeed for all institutions to raise their international fees by the full measure of inflation.”

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor of the University of Sunderland, said that if more universities increase their international fees in line with inflation, the market will adjust, but scholarships and bursaries may become even more important.

“If universities are generating less margin on international students, there is less money to support domestic students and the wider university civic and social mission, which includes research and knowledge exchange,” he said.

“With the drop in such margins, and a continuing freeze in domestic fees, this means that the amount of money that universities can generate will be lower, as the cost of delivering teaching and the wider student experience rises.”

Managing the freeze in domestic fees is increasingly difficult, suggesting that a fundamental review of the financial sustainability of higher education is required along with the freedom for universities to generate income from elsewhere, added Sir David.

Universities have highlighted that the £9,250 fee cap in England – raised by only £250, in 2017, since fees were trebled to £9,000 in 2012 – is now worth £6,600 in 2012 prices.

Len Shackleton, professor of economics at the University of Buckingham, said the significance of international student fees vary considerably across institutions depending on the proportion of overseas students they recruit.

“With home students’ fees not increasing in line with inflation, putting up international fees by a large amount will exacerbate the gap between home and international students, something international students notice and resent. The optics are not good,” he said.

Professor Shackleton said the effect of not increasing fees in line with inflation will vary considerably, but will not cause major problems in the short term.

“Over time, it will increase pressures to rationalise the student offer – closing down courses which don’t attract sufficient numbers, shedding expensive parts of degrees, and substituting larger lecture groups for smaller seminars and tutorials,” he said.

“We could also see some universities cutting staff costs by not replacing full-time academics when they leave, substituting part-timers or more junior staff.”

A Glasgow Caledonian spokesman said the decision to increase fees “should be considered within the broader context of consistently modest fee adjustments over recent years”.

“After conducting a comprehensive benchmarking review of UK competitors, and considering ongoing upward cost pressures, the university concluded that fee increases were necessary,” he said.

“While the one-year increase may appear higher than inflation when examined in isolation, we believe that when observed over an extended period, and in comparison to similar universities, our fee levels remain competitive, allowing us to continue to deliver academic excellence.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login