The far-left terrorist group Red Army Faction (RAF), which was active in West Germany throughout the 1970s and 1980s, officially disbanded in 1998. Despite a host of academic and popular analyses, there is not yet a narrative consensus about the group’s role in German politics and society – although it is striking that a recent exhibition, mounted first in Stuttgart and then in Berlin, showed the first signs of a musealisation of the topic. The RAF’s brutal tactics against what it perceived as a fascist state are, all theories and interpretations aside, hauntingly relevant to current developments. Then, as now, urban terrorism involving violence that profoundly disrupts daily life grabs headlines and deeply unsettles communities. And terrorism that involves young women mystifies the state, the media and the public all the more.

A “Wanted” poster dating from 1981, which was reprinted in magazines and displayed in public places at the time and is now integral to museum displays, drove this particular message home: 10 of the 15 RAF members crudely pictured in black and white snapshots and brief biographical sketches were female. These women and the cultural paradox they represented are at the heart of Patricia Melzer’s thought-provoking book. This well-informed and complex study of extremist female activity complicates matters in a most productive way. Melzer explores the links between the RAF and developments in feminist and political discourse; the range of reports and discussions in press coverage at the time that helped to shape public assessments and prejudices; and the patriarchal and cultural attitudes towards the women in the group.

In the process, she highlights how diverse these women’s take on violence really was, in stark contrast to the simplified popular reading of them as deviant “wild furies”. While terrorism is universally condemned, female armed struggle – the claim for political space by violent means – is inevitably gendered, and it is perceived not only as ideologically misguided (an error in judgement in undertaking acts that should be reserved for male terrorists) but also as “a fundamental contradiction in terms”. “How”, Melzer asks, “do masculinity and femininity operate as cultural parameters for political action?” In contemporary representations, these women were swiftly sexualised and turned into embodiments of evil. The angst that the RAF caused was, Melzer shows, further increased by the group’s being seen as a distinctively female threat, and it was at times politicised as a consequence of excessive emancipation.

Melzer carefully dissects feminist responses to media representations of women during the “German Autumn” of 1977, when violence escalated sharply; she also analyses the links between political power and the physical body during RAF hunger strikes; and she considers autobiographical writings by members. Particularly noteworthy is her chapter on the role of motherhood in revolutionary groups. Gudrun Ensslin, daughter of a Protestant pastor, and the journalist Ulrike Meinhof, who co-founded the RAF after they freed fellow militant Andreas Baader from a prison in Berlin in 1970, were eventually forced underground, leaving their children behind. The public was baffled by the perceived contradiction between the violent cause and the implications of motherhood; after all, militarism was associated with masculinity and the feminine domain with the anti-war movement. Both women were subsequently labelled “unmotherly” – Ensslin because she appeared to leave her son behind without hesitation, Meinhof because she surrendered to RAF group pressure and abandoned her twin daughters. In carefully distinguishing between “motherhood as institution” and “maternal love”, Melzer here offers new and nuanced interpretations of these events.

Female terrorists, then and now, preoccupy us. Death in the Shape of a Young Girl is a stimulating case study that encourages us to look twice: at media representations and ideological discourses, certainly, but also at our own established ways of seeing and the precarious roles allocated to women in the course of revolutionary aspirations.

Ulrike Zitzlsperger is associate professor of German, University of Exeter.

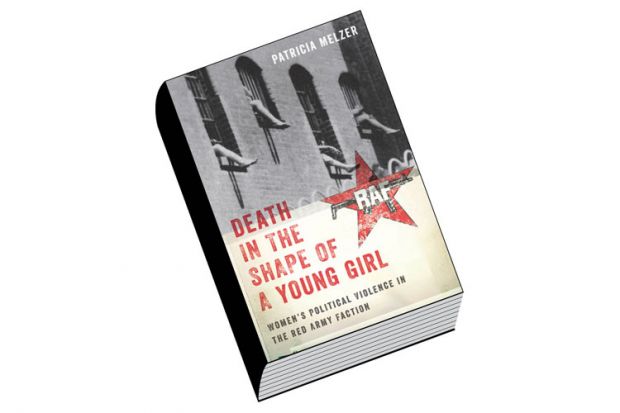

Death in the Shape of a Young Girl: Women’s Political Violence in the Red Army Faction

By Patricia Melzer

New York University Press, 352pp, £24.99

ISBN 9781479864072 and 807604 (e-book)

Published 19 May 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login