Source: Miles Cole

Heaney, maybe hearing few ideas from us, wanted us to learn things first, to render the local terrain of our own experience and languages

W. B. Yeats saw a choice: perfection of the life or perfection of the work. In schools we know the great devoted teacher, the classroom magician who transforms minds but doesn’t publish: he lives through his students. Then there is the respected but memorably strange scholar: lively on paper, offstage in the world.

Did Seamus Heaney make such a choice?

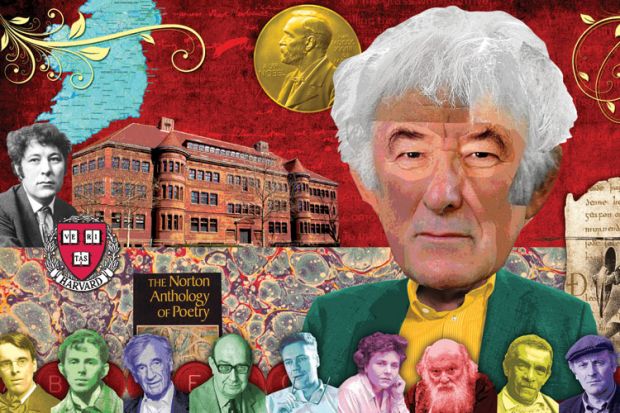

In the 1980s, his poetry workshop was held each winter at Harvard’s Sever Hall, a squat and thick-pillared place – waiting there, we knew his lines, “Between my finger and my thumb/The squat pen rests.” The literary Heaney was already present, both for the over-brushed Harvard students, and for us Ausländers who joined the class. (I had once met him on a college trip to Ireland in 1974; he read us bog poems and fed us dinner in his home. All I remember of the evening are the strawberries.)

Then he stepped in, hair dishevelled, damp-faced, hustling in from the snows. Later, we realised he looked like this every class, regardless of the weather.

He talked of Frost, and said: “New poems happen in a darkened room – I can only lead you to that place.” Then he asked: “Would anyone want to recite a poem by heart?”

Heaney taught by example, challenge, sly humour and genial conspiracy. He invited us to poetry’s long conversation the way you’d sneak someone in to hear wedding toasts. Which speech proved the love? What poet, for instance, could mix black humour and elegy? John Crowe Ransom: “It was a transmogrifying bee/Came droning down on Chucky’s old bald head/And sat and put the poison.” Chucky was a hen.

Who could praise himself nonchalantly, then make you agree? Frank O’Hara: for the Sun had told him, “you may/not be the greatest thing on earth, but/you’re different”.

Who could do you a nasty twist in a last line? Philip Larkin: “Or lied.” Heaney turned an air-dagger. From the poem Lament for the Makaris he might read us just the vowels or consonants: “don’t listen for the message now.”

W. C. Williams once warned, “no ideas but in things”; Heaney, maybe hearing few ideas from us, wanted us to learn things first, to render the local terrain of our own experience and languages.

We tried out three-line dinnseanchas – place poems – and made lists of names. I tallied up basketball phrases that sounded dirty, calling it “The Low Post”. But that year, Heaney had just published The Names of the Hare: “The hare, call him scotart/big-fellow, bouchart,/the O’Hare, the jumper,/the rascal, the racer.//Beat-the-pad, white-face,/funk-the-ditch, shit-ass.”

And hadn’t Heaney matched Ransom’s chilling wit in his early poem Mid-Term Break? The speaker looks at his younger brother killed by a car: “No poppy bruise, the bumper knocked him clear./A four-foot box, a foot for every year.”

We read only one book, The Norton Anthology of Poetry, skipping between eras, styles, conversations, gifts and secrets. Heaney had it memorised, quoting or misquoting (and improving?) lines from Beowulf to Elizabeth Bishop.

In his own constellation of favourite poems – by Dante, Robert Lowell, Zbigniew Herbert, William Carleton, Wilfred Owen –personal impulses clash with the needs of politically responsive art. They take risks that Irish poets face. Over this group hovered Osip Mandelstam; his witty satire, “the Kremlin Mountaineer” got him sent to Siberia.

Heaney grew restive with poems of droll satire, urban fatigue, ketchup-and-baloney family horrors, reflexive poems that punch at shadows. He warned us not to settle for “stuff just written in lines”. But who knew what sources we would use? “Cross your roots with your reading.”

He was the most admired teacher no one could imitate. The multiple displacements of culture, history and word-hoard left us admiring him, but looking to books and to ourselves for models. Does the best teacher produce students unlike him?

One outsider, Jane Brox, came from Nantucket, a pastry chef. Margaret Mead’s daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson, sat in. Both have produced terrific memoirs; neither sounds like Heaney. Nor do the Irish poets Paul Muldoon or Sinéad Morrissey exactly follow him. Yet Heaney anchors the poetry canon in several countries, and hundreds of poets know him simply as “Seamus”.

During a conference in his office Time magazine calls. He pronounces his name for them; next week their article gets it wrong. He attends many poetry readings – the audiences have come because he will introduce the poets. In restaurants, he chooses a small back table so he can finish a meal. In his apartment the phone is always ringing – he doesn’t know he can unplug it, and sits there typing out with two fingers the poem Alphabets, which he’ll read at a ceremony. The ceiling of his bathroom has fallen in, chunks of plaster are piled in the tub. He’s got about 10 minutes to spare, still damp-faced, bent in concentration as he finishes the poem, “letter by strange letter”.

Someday, when “Late 20th Century American Poetry” is taught, we will trace how Boston, once home to local sages Emerson and Longfellow, then needed to import great writers from everywhere but New England: Joseph Brodsky, Derek Walcott, Saul Bellow, Robert Pinsky, Geoffrey Hill, Elie Wiesel, Christopher Ricks, and Heaney.

Which of them made Yeats’ choice, life or work? Brodsky and Walcott produced “a trail of tears”. Seamus Heaney’s generosity, in his poems and his life, leaves a quiet answer.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login