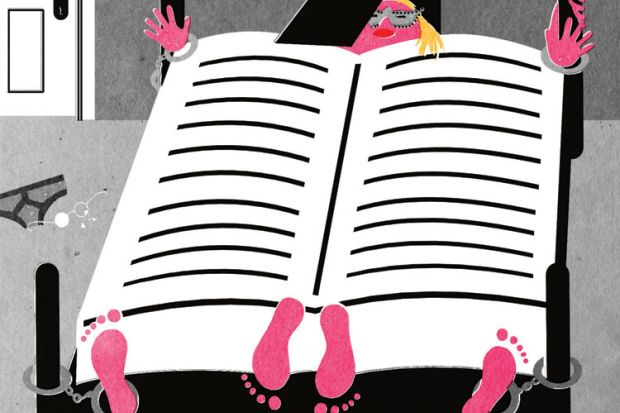

Harvard University has been making news with its announcement of a ban on sexual relationships between university academics and undergraduates, and between supervisors and their graduate students.

Although most US universities have guidelines discouraging staff-student liaisons, Harvard is among the first to close the gap between expectations of faculty behaviour and the formal means to enforce such expectations.

The gap is just as wide in the UK. In an interview with Times Higher Education some years ago, Mary Beard, professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge, suggested that “in some ways we have to accept that there is an erotic dimension to pedagogy” and that although it is “undeniable that some students and staff have been hurt by these kinds of relationships”, it is “also undeniable that there have been people who have gained from them” (“Sex and the university”, 22 May 2008).

Academics are well placed to mobilise suave – and culturally ingrained – rhetoric in rejecting oversight of their sexual and emotional behaviours and attitudes. Amid warnings about “paternalism” or “neo-puritanism”, three points are often trotted out: that students are consenting adults; that power relations abound in all employment sectors; and that love conquers all.

But these are weak considerations that deflect attention from the unique structural vulnerabilities students encounter. Undergraduates, especially in their early months, are vulnerable precisely because they do not believe that they are. For many, it is the first time they have engaged with adults as – superficially, at least – intellectual equals. That can lead them to overestimate their ability to consent to a relationship for which they are not necessarily prepared emotionally and one that can have implications that they could not have foreseen, such as confidence-eroding doubts about the true quality of their work. Appeals to the power of Cupid’s bow are way off target in such a context.

It is often argued that such concerns about vulnerability are much less valid for graduate students. But it is precisely in respect of postgraduates that the force of academic defensiveness bites hardest and most troublingly. Some might be older and wiser than those new to university, but not disproportionately so. Many postgraduates are still relatively immature emotionally. More importantly, however, postgraduates are exposed to unique pressures because of the nature of their environment and the kinds of capital that circulate in academia.

In the humanities, which are my broad subject area, whether one likes it or not, supervisors largely determine the initial course and character of careers, via the quality of their guidance and feedback through to the choice of viva examiners, the strength of their references and, ultimately, the reputational benefits of having studied under them. Postgraduates cannot easily change supervisor without damaging this fragile nexus and raising questions about their intellectual aptitude. (Academics are disinclined to endorse supervisory changes where criticism of their supervision is implied.) This reputational nexus extends to the other academics within a department, who also critique a postgraduate’s work, offer pastoral support, provide additional references, feature in acknowledgements and, in times of difficulty, embody the possibility of seeking alternative supervision.

The pronounced nature of reputational influence in the academy trumps observations about the adulthood of postgraduates or the ubiquity of power relations in other sectors. Graduate students, to a greater extent than academics, desperately require a stable and nurturing context to foster their embryonic research and intellectual identity. Romantic relationships distort these contexts.

These distortions exist even if, as the defensive anecdotes attest, relationships ultimately “end well”. Everyone knows of an academic who married a student; but for every such “happily ever after”, how many other relationships stagnate or dissolve, leaving a bewildered and insecure postgraduate student uncertain of their situation? Rhetorically, the nostalgic focus on good relationships overlooks the underlying dynamics that suffuse postgraduate study and erupt when things go wrong and students – their reputations under scrutiny – are forced to scrabble for alternative supervision or guidance where it is available, or to launch into a more wholesale reconsideration of their course of study where it is not.

If the eroticism dormant in teaching is powerful and ubiquitous, as Beard suggests, this should actively motivate rather than undermine efforts to formally regulate sexual and emotional behaviour. In this respect, the academy should learn from other similarly “transference heavy” professions (to use psychoanalytic jargon) such as psychiatry or school teaching.

Ironically, those who romanticise the frisson of intellectual engagement in close study overlook the famous abstemiousness practised by the father of tutorial-based teaching. Socrates was also aware of the sexual intensity generated by certain kinds of philosophical conversation. But he privileged his concern for his interlocutors’ intellectual development over his own physical gratification, keeping his hands to himself even in the presence of Alcibiades – perhaps the most desirable man in Athens. Harvard is right to establish consequences for academics who cannot emulate his example.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login