Source: Paul Bateman

Mandela saw equality of opportunity through education as the key to emancipation, a principle yet to be realised in South Africa, or elsewhere

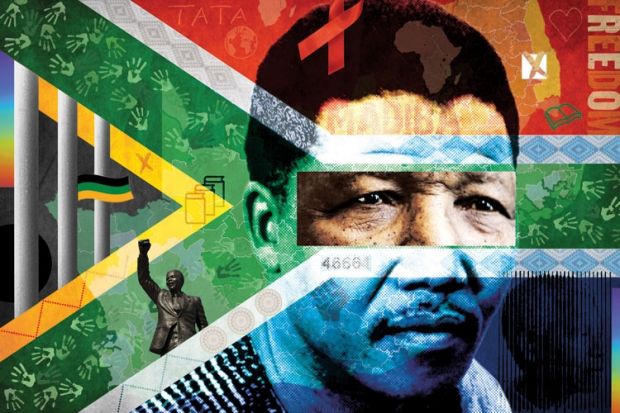

What more can be written about Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, world icon? His political longevity embraced the entire span of formal apartheid, from before the election of the National Party in 1948 and to the end of the first term of South Africa’s democratically elected parliament in 1999.

His political transitions were from trained guerrilla fighter and founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress, to elected president and Nobel Peace Prize winner. As the conditions of his years in prison were steadily relaxed in the 1980s he could walk in the Cape Town suburbs with no one recognising him. Within a few months, and for the rest of his 95 years, his was perhaps the best-known face in the world, with every detail of his life in the public gaze. For South Africans he is Madiba – his clan name. His reach was far beyond established politics: famously, of course, in sport but also into the quirks of national culture. Because of him, we could abandon jackets and ties and wear bright Madiba shirts at any occasion.

Madiba had a lifelong respect for education: in his early years at Fort Hare; in pursuing legal qualifications (and writing examinations under threat of a death sentence in jail in Pretoria); on Robben Island, in his now famous organisation of seminars while working in the blinding light and dust of the lime quarry. He saw equality of opportunity through education as key to emancipation, a principle yet to be realised in South Africa, or elsewhere.

This respect for informed and independent thought and for freedom of expression was apparent in one small encounter that I shared with others in 1999 in the last year of his presidency. With little warning or ceremony, some 20 of us from the University of Cape Town, led by our vice-chancellor, were invited to Mandela’s nearby home. President Mandela wanted a seminar to evaluate the successes and failures of his time in office. For three hours he responded to our commentary: on reconciliation; on economic policy; on HIV and Aids, then growing to epidemic proportions in South Africa. His respect for informed criticism and research-based perspectives was palpable. When the time came for us to leave, he showed us out himself, waving as we drove away.

Mandela’s leadership in combating HIV/Aids was his greatest contribution after standing down as president. In our meeting with him, he had acknowledged that he had been too slow to recognise the danger, oversensitive to the traditional reticence to talk about sex or sexuality. He went on to lead a global campaign for awareness and effective and appropriate treatment, despite the notorious denialism of his successor as president, Thabo Mbeki.

For South Africa, Mandela’s death marks the end of being different as a country, whether because of the violent abuse of basic rights through the statutory racism of apartheid or for its image as the Rainbow Nation, born when Madiba walked out of prison and into the lenses of the world media in February 1990. This is a symbolic transition, since Mandela retired from public life a decade ago, but an important one. South Africa’s future depends on countering inequality and poverty, more acute now than 20 years ago, and dealing with the widespread perceptions of incompetence and abuse of power that have severely damaged the reputation of the ANC since Mandela stood down from the presidency after his single term of office.

What does Mandela mean for the world? Many things, which will become clearer with deeper reflection. There is nostalgia for the example of the life dedicated to the public good, now a chimera in an age of cheap populism. There is affirmation for the principle of leadership through values. And here, Mandela’s life and death could be a mirror from the South back to the North. We should remember that Margaret Thatcher’s government denigrated him as a terrorist. We should also remember that apartheid was founded in the racism of British colonialism. And the case of asylum seeker Ifa Muaza would be painfully familiar to Mandela; weak, close to death and forcibly flown around the world by the British government for 20 hours in a botched attempt at deportation. If this is how we treat a man seeking asylum with just cause today, how can we be said to subscribe to the values for which Mandela lived?

All of us who claim Mandela as a moral lodestone should remember that this requires Socrates’ “considered life”. Will a British prime minister, in his or her last months in office, open up Chequers for a reflective and critical evaluation of the ways in which they have used their time of power and opportunity?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login