View the THE Asia University Rankings 2022 results

Shortly after the World Health Organisation declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic in March 2020, several higher education experts predicted that the crisis would reshape international student flows. East Asia would claim a bigger share of overseas students, with some nations becoming regional higher education hubs, while universities in the West would be likely to suffer, according to this narrative. These views were based in part on the assumption that East Asia would recover more quickly from the coronavirus crisis, rapidly checking its spread and returning to face-to-face teaching, than other regions.

Fast-forward two years and the landscape looks quite different. While it is true that the overall number of Covid-19 cases and deaths is far lower in many East Asian countries than it is in the UK and the US, strict national Covid policies mean this has not necessarily resulted in a speedy restoration of in-person teaching.

Mainland China’s borders are still largely closed, meaning that nearly 500,000 international students are stranded outside the country, and Japan is only admitting up to 7,000 entrants per day, leaving tens of thousands of students waiting.

The geopolitical terrain has changed, too. Will the Russia-Ukraine war affect student flows in and out of Asia, and within the region? And how will the Hong Kong national security law affect domestic and international students’ desire to study in the city?

Asia University Rankings 2022: results announced

“We’re in the middle of transition,” says Anna Esaki-Smith, co-founder and managing director of the research consultancy Education Rethink. “We’re in a period where what we thought was the status quo is no longer the status quo. And there is potential for the current status quo to change again as well.”

Do these combined Covid-19 and geopolitical factors reduce the likelihood of East Asia’s emergence as a regional higher education hub, or slow down such a trend?

One expert who was quick to forecast Asia’s rise in light of the pandemic is Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, who predicted that some of the East Asian students who would have travelled to North America, western Europe, the UK and Australia would instead head to other East Asian countries, adding that such a shift was “likely to be permanent”.

He also anticipated that health security would “for a long time become a major element in the decision-making of families and students about where they go for education”.

Speaking today, Marginson admits that some of his hypotheses have not come to pass, at least in the short term.

“One of the things we have learned is that [there is no evidence that] public health concerns – the danger to life constituted by the pandemic – have really been a lasting factor in our ability to discriminate between countries,” he says.

“There’s no evidence that because the US and the UK have higher casualties, certainly in the first year, that was going to change the pattern. And there’s no evidence that the fact that the East Asian destinations were safe played into mobility flows.”

The pandemic has also proved that “demand for the UK and the US is really strong, and it’s different to the rest of the world”.

“The rest of the world has to entice people with scholarships and so on. But people from around the world go to the US and the UK in great numbers, and Australia and Canada are second-best versions of those two primary countries,” Marginson says.

“As soon as you got back to the point where people could go into the US again, numbers surged up. And in the UK, where a real effort was made to maintain numbers and increase them through the pandemic, that was successful, against all the odds – no one expected it. It just shows how strong the student demand factor is.”

Does this mean that even when China and Japan remove border restrictions, they are unlikely to take many international students away from the West?

“It’s not just because of the difficulty in accessing China at the moment, and so on. It’s because for mobile students, the English language countries are still positioned in this distinctive way, and that long-term demand plan hasn’t changed much,” he says.

However, Marginson adds that in the “very long term – 10 to 20 years – you will see an increase in Asian higher education mobility” and “East Asia is going to become a bigger hub or a bigger set of hubs”, because several countries have strong university systems and relatively strong economies, and the value of being able to communicate in Chinese is likely to rise.

Esaki-Smith agrees that “the fundamentals will determine what becomes an established study hub and what does not”, and this is “not going to be determined really by Covid”.

However, she adds, Covid could “emphasise the reasons not to go to a [particular] country to study”.

“Hong Kong, at one point, was earmarked as being a global hub. It had highly ranked institutions, a lot of English language curriculum, and it had opportunities in mainland China. It was a very safe place to study. However, after the Umbrella Revolution, the crackdown that occurred [from mainland China], and now with the Covid restrictions, to me, all of that will contribute to Hong Kong becoming less attractive as a host country,” she says.

“Picking a country to study in is a multifaceted decision, and it won’t be determined, I don’t think, by a Covid restriction. But if it’s one of several deterrents, it could be the final factor that makes students decide I’m going to pick someplace else.”

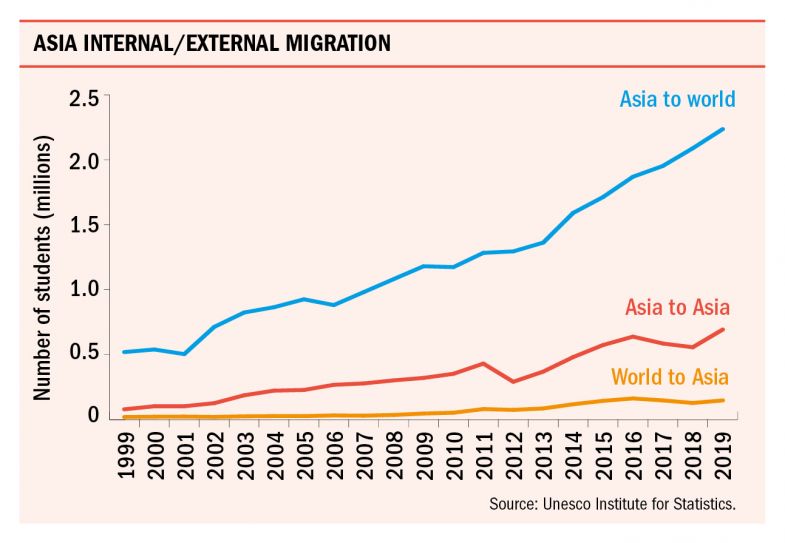

There is not yet reliable global data on international student flows during the pandemic, but historical figures from the Unesco Institute for Statistics show that an increasing share of mobile students in Asia were staying within the region even before the pandemic.

In 2000, 16 per cent of mobile Asian students studied in another country in the continent; by 2019, this share had risen to 24 per cent. The overall number of mobile Asian students more than quadrupled during this period, from 640,000 to 2.9 million. However, the number of students from the rest of the world visiting Asia was still relatively low in 2018, as shown in the chart (below).

Janet Ilieva, founder and director of the international mobility research consultancy Education Insight, says that although the share of internationally mobile students globally might have stalled during the pandemic, it is likely to accelerate again once travel restrictions subside. The share of higher education students worldwide who studied abroad increased from 2.1 per cent in 2014 to 2.6 per cent in 2019, according to Unesco data.

At the same time, the increased flexibility and extended, even cross-border, reach of programmes observed during the pandemic is also likely to remain a trend, she adds. This will be aided by the softening of transnational education regulations that has occurred in many countries, enabling more universities to teach online.

“We’re probably seeing a liberalising of our definitions of mobility,” Ilieva says. “International experiences are given greater importance through physical mobility of students but also international programmes that students can access [from around the world]. I would expect to see stronger partnerships and an increase in the variety of collaborative teaching programmes that offer greater flexibility compared to traditional forms of education.”

Esaki-Smith says that another potential trend to watch is whether increasing numbers of Asian students will remain in their home countries and not travel at all as domestic education provision improves.

Recent Times Higher Education analysis of graduate employment reports published by China’s 10 top-ranked universities found that the proportion of postgraduate students enrolling with a foreign institution has declined across the board since 2017.

However, Futao Huang, professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, does not think that there will be a significant shift in Asian students staying at home.

“Particularly for Chinese students, they still want to go to advanced Western countries like the US, the UK and Australia. The governments in [China and Japan] still encourage domestic students to go abroad,” he says.

One question that has frequently made headlines in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the extent to which China will ally with Russia. A subsequent question for the realm of global higher education is whether the answer is likely to impact China’s attractiveness among international students.

“It’s really hard to call,” says Marginson. “The only obvious thing is that in the medium term, movement in and out of Russia is really reduced.”

He adds that China is likely to try to rebuild its international student growth once its borders reopen, but its success in that will depend on “whether China is an attractive place for the world’s students to want to go to for economic reasons, and whether China is partly decoupled from the West or still connected”.

“That’s where I think it’s just unknown. A lot of world history is going to depend on how that plays out.”

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s national security law is likely to mean that, in the long term, more Hong Kong students opt to go to mainland China, while Hong Kong may struggle to attract international students, he says.

In March, China expert David Zweig, professor emeritus at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said that “if [China] insists on zero Covid, then its future role as an academic hub will be severely limited, as it will never get rid of Covid and students will go only if they have no other options”.

However, he believes that the country’s stance on Russia is unlikely to influence its relationship with other Asian countries, and therefore whether it can attract students from the region.

“The Americans and the Europeans might be affected by China’s policy in Ukraine. I don’t think the Koreans, the Japanese will be overly concerned,” he says.

But he says the attitude of South Korea’s new president, Yoon Suk-yeol, towards China could be a factor, given that a high share of international students in China come from its neighbour. The conservative leader has taken a harder stance on China than the previous president, the liberal Moon Jae-in, and has made clear that he plans to strengthen trade and security ties with the US.

“China has reasonably poorer relations with most of the countries around it these days. Ties are not so good with Korea…Japan,” Zweig says.

“Student flows may depend more on bilateral relations than the larger geopolitics.”

China’s slowing economy is another area to watch, according to Zweig.

“For many young people going on to study, I think their main purpose would be to get a job,” he says.

“Lots of Chinese college students are graduating and…looking for jobs. And they could be competitive, especially if more Chinese students graduate with MBAs and are reasonably fluent in English – that [creates] real competition for the foreign students.”

Meanwhile, Sang-Gil Jeon, professor in business and economics at Hanyang University and former chairman of the Korean Association of Human Resource Development, believes that South Korea might emerge as a regional education hub, partly because of the conflict between the US and China.

“Chinese students who had hoped to study in the US will turn towards South Korea, a country also known as one of Asia’s educational powers,” he says.

Whatever the impact on student flows, from Covid-19 and geopolitics, experts agree that global higher education is in a state of flux that is likely to remain for some time.

“There is more and more uncertainty, and [this is] becoming one of the factors, and possibly one of the key considerations, in terms of deciding where to study,” says Ilieva.

Students will want to “choose a country where uncertainty is all right, and that still provides a safety net of options”.

后记

Print headline: A check on the trajectory