India has increased its share of the top universities in the Times Higher Education BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017, but China still has the highest density of leading institutions in the developing world.

The Indian Institute of Science breaks into the top 15 for the first time this year, in 14th place, thanks to an improved teaching environment and greater research influence. The Indian Institute of Technology Bombay has also reached its highest position after climbing three places to 26th, boosted by improved scores across all the five pillars underlying the methodology.

Overall, the country has 27 universities in the top 300 ranking, 19 of which make the top 200 (up from 16 last year), making it the second most-represented nation in the table.

Despite India’s gains, however, China still dominates the list, taking 52 – or more than one in six – places in the top 300. Six of these make the elite top 10, including Fudan University, which rose 11 places to reach sixth place this year, and Peking and Tsinghua universities, which hold on to the top two spots for the fourth year running.

- Should emerging economies nurture world-class universities?

- Creating world-class universities in Africa

Anurag Kumar, director of the Indian Institute of Science, said that increased government science funding in recent years has enabled the university to enhance grants for new hires, invest in state-of-the-art infrastructure and encourage interdisciplinary research.

The institution is working hard to attract more scientists from other countries, he added, while also noting that India’s large youth population is a “great asset, especially since they are getting better education right from primary school to college”.

“This growing talent pool augurs well for the country,” he said. “The government is doing its part by enhancing its education and research budget across the board.”

However, while the two Asian giants have improved their showing, the performance of the other BRICS nations is waning, largely because of increased competition as a result of expanding the list to rank 300 universities from 41 countries, up from 200 institutions in 35 nations last year.

Brazil no longer has a university in the top 10, as the University of São Paulo slips four places to 13th, its lowest ever position, while half of South Africa’s eight universities have fallen.

- How to make Latin America’s universities stronger

- Browse Times Higher Education's full portfolio of university rankings

Russia’s performance is more mixed; while 10 of its 24 universities have dropped places, Lomonosov Moscow State University holds on to third place amid increasing competition from China, and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology climbs 81 places to 12th, thanks to an improved performance across teaching, research, knowledge transfer and international outlook.

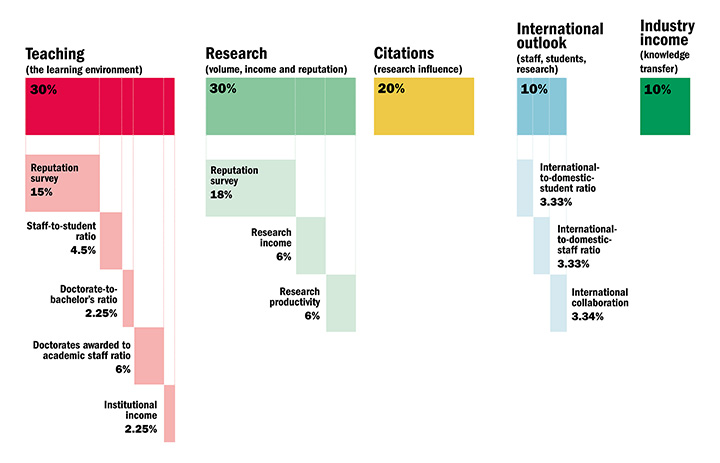

The THE BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings use the same 13 performance indicators as the flagship World University Rankings but are recalibrated to reflect the development priorities of universities in emerging economies.

The table includes only institutions in countries classified as “advanced emerging”, “secondary emerging” or “frontier” by the FTSE.

Claim a free copy of the BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings digital supplement

BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017 results: top 10

| BRICS 2017 rank | BRICS 2016 rank | Institution | Country | WUR Rank |

| 1 | 1 | Peking University | China | 29 |

| 2 | 2 | Tsinghua University | China | 35 |

| 3 | 3 | Lomonosov Moscow State University | Russian Federation | 188 |

| 4 | 4 | University of Cape Town | South Africa | 148 |

| 5 | 7 | University of Science and Technology of China | China | =153 |

| 6 | 17 | Fudan University | China | 155 |

| 7 | 10 | Shanghai Jiao Tong University | China | 201-250 |

| 8 | 6 | University of the Witwatersrand | South Africa | =182 |

| 9 | 8 | Zhejiang University | China | 201-250 |

| 10 | 5 | National Taiwan University | Taiwan | =195 |

View the full BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017 results

Chinese dominance unthreatened by debutants

India has a growing presence in the rankings, but China continues to power ahead even as new countries join the running

When soon-to-be Indian prime minister Narendra Modi addressed Veer Narmad South Gujarat University in 2011, he said that a technological and knowledge “revolution” had shrunk the world into a “global village”.

“Whatever education [a] university or institute of higher education imparts, it must achieve the global level of benchmarking given the vastness and diversity of [the] global village we live in today,” he told staff and students at the institution’s 42nd annual convocation.

Earlier this year, Modi showed that he was committed to this global benchmarking of the country’s universities by launching the government’s first ranking of Indian universities and establishing a new funding-backed project aimed at catapulting Indian Institutes of Technology to the top of world university league tables.

India still lags behind other major economies in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings; no Indian universities make the top 200 of this list.

But when you compare the country’s showing with that of other emerging nations, it is one of the leading performers, as the THE BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017 make clear. Its flagship university, the Indian Institute of Science, breaks into the top 15 for the first time this year, in 14th place, thanks to improved scores for its teaching environment and research influence, while the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay climbs three places to 26th, its highest position ever, because of its improved scores across all the five pillars underlying the methodology.

In fact, India could soon overtake Taiwan as the second most-represented country in the top 200 of the table, behind only China. Overall, India has 19 universities in the top 200, up from 16 last year, while Taiwan has 21, down from 24.

But despite India’s gains, China still dominates the list of the best universities in the BRICS and emerging economies. The People’s Republic claims more than one in six places in the newly expanded top 300 table, a tally of 52 universities. A staggering 44 of these make the top 200, five more than last year, while six feature among the top 10, including Fudan University, which has risen 11 places to reach sixth place. Meanwhile, Tongji University makes its debut in the top 25 at joint 24th place, having jumped 28 positions.

Both institutions have attracted much higher levels of industry income this year. Fudan has also improved both its teaching and research environments, while Tongji has earned more citations.

Ka-Ho Mok, vice-president and chair professor of comparative policy at Hong Kong’s Lingnan University, says that China’s recent success in the rankings can be attributed largely to the government’s centralised funding system and the concentration of resources on selected disciplines.

In contrast, India has a “far more decentralised model of university governance”, he says, which means that the higher education system is reliant on individual states establishing policy and funding mechanisms.

He thinks it is likely that a small number of Indian universities will keep improving in the rankings, but it will be difficult for the Indian higher education system as a whole to “outperform other Asian economies” such as China, Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea, which have all made gains in the THE World University Rankings in recent years.

“The curve is very steep. They will have to fight and work very hard,” he says.

Richard Everitt, director of education at British Council India, also warns that “reform is slow in India”, and although the country has one of the biggest higher education systems in the world and “some good institutions”, it still “doesn’t perform well on a global platform”.

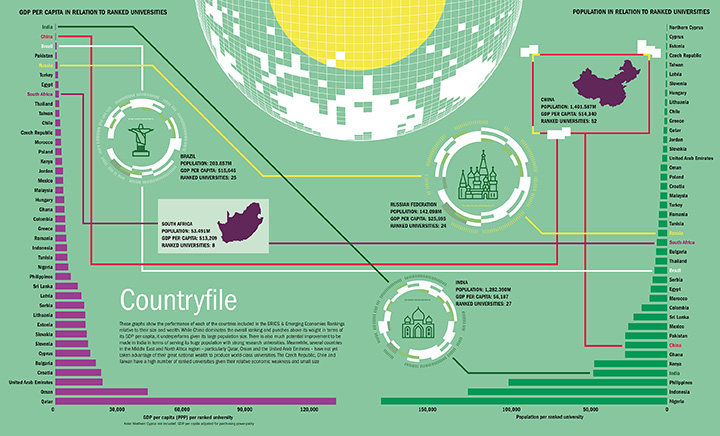

Performance of countries relative to their size and wealth

“There hasn’t really been an effective higher education reform process to catapult Indian institutions to the forefront of league tables,” he says.

He welcomes the country’s latest initiative to achieve this goal, but warns that “the track record so far suggests that it may be difficult to make rapid change”.

Another key challenge for India, Everitt says, is a “chronic lack of faculty”, noting that 40 per cent of all academic positions at the country’s universities “go unfilled”.

He adds that most Indian universities are “very good at teaching, but few of them have very strong research depth as well”, which he says is partly due to the fact that research institutes are separate from universities.

He stresses that these challenges are a “global issue, not just an Indian one”.

“India is going to provide about a quarter of the world’s workforce by 2030,” he says.

Despite these setbacks, Mok says that India outperforms both China and Japan in terms of the proportion of publications and citations relative to gross domestic product, and it surpasses China on the proportion of published papers with an international co-author.

But while Asia’s two giants have risen in the rankings, not all the BRICS nations have performed so well.

Although 11 of Brazil’s 25 representatives are appearing for the first time, the majority of the other 14 institutions have dropped places in the ranking. The country no longer has any representatives in the top 10 as the University of São Paulo has slipped four spots to 13th, its lowest position ever.

In addition, half of South Africa’s eight universities have fallen.

Klaus Capelle, rector of Brazil’s Federal University of ABC (UFABC), which is ranked for the first time at joint 167th place, says that Brazil has an “enormous talent pool”, with more than 50 million people – or 25 per cent of its population – aged 15 to 29 years.

He adds that the country’s higher education system has undergone significant expansion and improved in quality over the past 20 years.

“Well-run funding agencies and world-class laboratory facilities contribute to a healthy ecosystem for higher education and research,” he says.

However, he continues, the private higher education sector “struggles to strive for economic sustainability and academic quality in an unfavourable economic environment”, while the public sector suffers from “archaic public service regulations, outdated governance and insufficient funding”.

He recommends that Brazilian universities diversify into a system with institutions of different sizes and missions, noting that “excessive regulation” of both the public and private sector means that universities are “rather similar in priorities, modes of operation, curricula, faculty recruitment and promotion policies, organisational design, [and] mission statements”.

“A more diversified system would be more effective in resisting crises and in offering higher education to larger parts of the population,” he says.

BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings 2017: methodology

This year, the number of universities included in the rankings is expanded considerably, using our rigorous performance indicators

View this year's BRICS & Emerging Economies University Rankings methodology in full

Other drawbacks include the fact that donations to universities in Brazil are taxed, instead of encouraged through tax benefits as in many northern hemisphere countries; endowment funds are “a little-explored concept”; and collaborations between universities and industry are “seen with suspicion by courts and regulatory bodies and face bureaucratic obstacles”.

Meanwhile, the Russian Federation’s performance is more mixed. It has 14 institutions in the top 200, down from 15 last year, several of which have either gained or lost several places.

One climber is the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT), which has leaped from 93rd place in last year’s table to 12th this year, thanks to improved scores for research and citations.

Tagir Aushev, vice-rector for research and strategic development, says that MIPT was traditionally focused on education because all research was conducted in the research institutes of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

But over the past 10 years, the university has started to invest significant amounts of money in its own research infrastructure, buildings and equipment, he says.

“As a result of this, and the financial resources of Project 5‑100 [a government initiative to propel five Russian universities to the world top 100 by 2020], from 2013 onwards we opened about 40 research labs headed by the world’s leading scientists,” he says.

“It was quite a significant change in the university’s strategy, and it has paid off. Our scientists have started to achieve global-level scientific results and publish them in the most prestigious scientific journals. Taking into account the fact that citation value used for the ranking calculation is averaged for the past five years, we expect that the impact of our researchers’ work will continue to grow.”

Several new countries, including Bulgaria, Latvia, the Philippines and Tunisia, appear in the rankings this year, largely as a result of the expansion of the table to include 300 universities, up from 200 last year. Croatia and Northern Cyprus also both join the top 200, with the University of Zagreb claiming joint 196th place and Eastern Mediterranean University occupying joint 173rd.

There are also improvements for some of the more established emerging economies. Colombia has two top 100 representatives for the first time, with the University of the Andes claiming joint 68th place and newcomer Pontifical Javeriana University landing at 95th.

Meanwhile in South Asia, Pakistan has three institutions in the top 200, up from two last year, although its existing representatives have fallen, and Sri Lanka joins the list for the first time.

Everitt says that all of South Asia’s higher education systems are “struggling with the fact the institutions were set up to educate the elite of the country 50 years ago” and “now they’re having to educate the masses”.

However, the South Asian region has huge potential for higher education success because of its growing youth population and the development of technology, and the countries are striving to rapidly meet ever-increasing demand while improving quality, he says.

“All the South Asian institutions are looking for ways of delivering low-cost online education.”

Everitt adds that a disadvantage compared with other Asian and Western regions is that very little trade occurs between the countries of South Asia, noting that there are no commercial ferry boats between Sri Lanka and India.

But he says that universities could be a key driver of stronger regional ties.

“There’s a big opportunity for universities in the knowledge economy to help move that relationship forward,” he says.