No university leader needs me to tell them how challenging it was to suddenly switch to online teaching during lockdown. But our experience is that, if anything, it is even harder to get students and staff to return to the campus when the restrictions lift – at the same time as retaining the positive changes implemented during lockdown and adjusting budgets to reflect much lower numbers of international students.

New Zealand’s geographical isolation and its strict lockdown imposed on 25 March have resulted in low infection rates and a very small number of deaths. As a result, by early June, most of the restrictions had been removed. This made it possible for us to reopen, provided that we increased hygiene measures, continued to provide online learning access for those who still could not return, and implemented comprehensive tracking of the thousands of individuals who were physically present.

The need to be able to carry out contact tracing required us to partner with an external technology firm to rapidly develop a secure, privacy-protected system whereby staff, students and visitors opt in to scan one of the 4,000 QR codes we have put up as they enter or exit every room. In the process of defining our trackable spaces, we discovered rooms in far-flung corners of our two campuses that administration did not even know existed!

We created a campaign to explain the QR code system featuring my border collie, Ella, who achieved rock-star status on campus following her brief cameo appearance in one of the first video messages I made from my home office. Ella takes full credit for the strong uptake of the system and for the interest in replicating it at a number of overseas universities.

Still, it quickly became clear that some staff were reluctant to return. Some had residual health concerns and uncertainty about the potential return of the virus. Others had learned to enjoy working from home. We have needed to remind staff that their ability to work from home rests on the social networks and relationships established over long periods in an office environment, which cannot be sustained and enhanced remotely. So while we are completely rewriting our flexible working policy as a result of lockdown, it will still require regular, if not exclusive, work in the office in most cases.

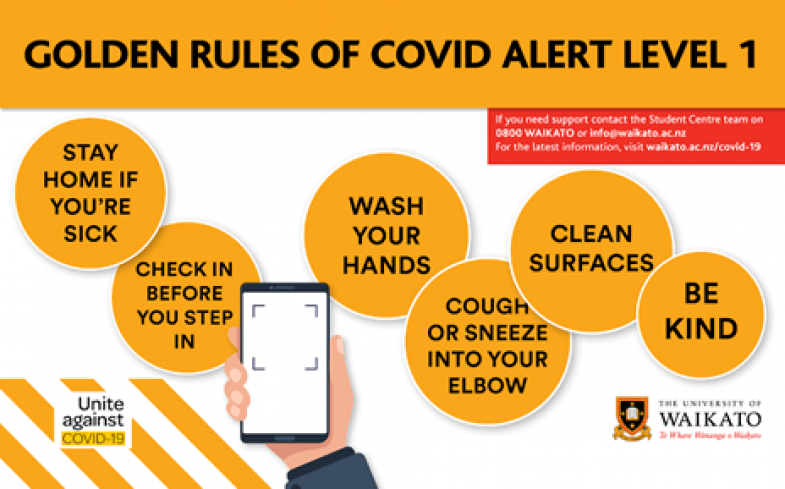

Hygiene is another challenge. Our campuses have many common spaces that can host hundreds of people – not to mention corridors and walkways through which thousands pass daily. While we have deployed hand sanitiser and increased the frequency and intensity of cleaning, our primary response has been in communications reminding people of the ongoing need to take great care with hygiene. Our “golden rules” campaign mirrored the key messages being promulgated by the government.

As the last week has demonstrated, the requirement for physical distancing can change at short notice, so we have replaced large face-to-face lectures this trimester with combinations of short videos, additional small-group activities, encouragement of social learning with peers and self-directed activities. We have also moved away from traditional exams in favour of online open-book tests.

This has resulted in expressions of concern from a minority of staff, students and parents, but we are confident that change was inevitable, albeit hastened by the pandemic. Attendance levels strongly suggest that students do not find lectures stimulating or effective, and 60 per cent of our courses already do without a formal final exam. We are closely monitoring the effects of our new approach on learning outcomes and the results so far are encouraging.

Another benefit of our lockdown experience has been an increased concern to provide equitable learning opportunities for students with financial and logistical difficulties. A combination of government and university funding provided learning devices and internet connections for students during lockdown, and many staff are contributing to a student hardship fund through payroll giving.

As we reopen our campuses, a particular concern relates to international students. Their numbers are likely to be 30 per cent down on last year and could be worse next year if we are unable to replace those who graduate in early 2021. Currently, the border remains closed to all but New Zealand citizens and permanent residents, so we have hundreds of students studying online in their home countries while they wait for the border to open. Their interest in online study will wane quickly if they lose hope of entering New Zealand to complete their studies.

Is there an alternative operating model for universities that does not involve international students? Some opponents of special quarantine arrangements for international students imagine so. But all vice-chancellors understand the reality that international students have allowed our domestic students to benefit from a breadth of programme offerings and quality of facilities that our government funding does not support. Unless ministers are prepared to put in a lot of extra money, the absence of international students will require universities to reshape all aspects of our operations.

The pandemic has hastened positive change by forcing us to rethink the student experience in light of the new options that technology gives us to promote quality teaching, learning and assessment. The cohesiveness of the university community has also been enhanced by the shared response to adversity. But unless we can safely reopen our borders to international students, more challenging changes are going to be forced on vice-chancellors very soon.

Neil Quigley is vice-chancellor of the University of Waikato, New Zealand.

后记

Print headline: Work in progress: proceed with caution