Talk earlier this year comparing the pay of UK vice-chancellors and top footballers has made me reflect that the Russell Group may be missing a trick.

The group is often described as the “Premier League” of UK universities. Its 24 institutions receive more than three-quarters of research council funding and more than four-fifths of charity research income. On average, each member university has 25,000 students.

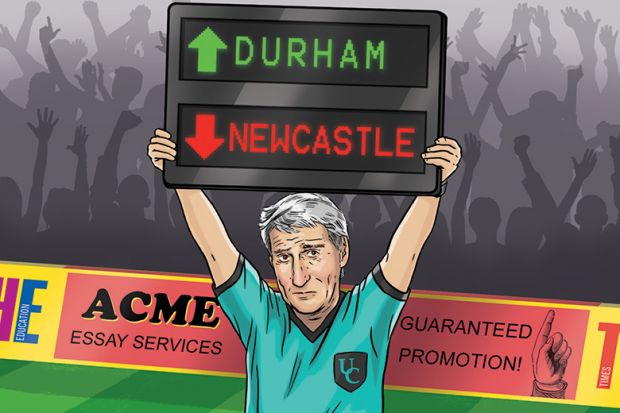

But there’s a crucial difference between the Russell Group and the real Premier League. No one gets relegated from the Russell Group. This is particularly odd when you recall that, in 2013, four universities – Durham, York, Exeter and Queen Mary – were “promoted” from the now-defunct 1994 Group. Universities, it seems, are only playing at elite competition. I propose they take the footballing analogy further, and act like a proper Premier League.

Let’s go back to 2012. Then, the Russell Group consisted of 20 universities – just as there are 20 teams in the English football Premier League. Four universities – OK, it’s only three in football – were promoted, so the bottom four universities should have been demoted. Looking at the university league table (specifically, the one in the popular Sunday Times Good University Guide), Cambridge was in top position, followed by Oxford, Imperial College London and the London School of Economics. In the middle were universities such as Edinburgh and Southampton. And in the bottom four places were Liverpool, Queen’s University Belfast, Leeds and Cardiff.

I’m sorry. Those four should have gone.

What would have happened the following year? Again, in 2013, the same four were in the top places, although in a different order – just as in football, where it’s often predictable which teams will finish in the top places (and qualify for European-level competition). Languishing at the very bottom, ripe for relegation, is the only-just-promoted Queen Mary. Football teams that are promoted one year only to be relegated the next are common enough to have earned their own specific term: “Yo-Yo” clubs. It’s happened a dozen times to Birmingham City.

The other three universities joining Queen Mary in the second tier? From the bottom up, it would have been Manchester, Sheffield and – there’s no easy way of putting this – Newcastle, my own university.

It’s OK. We’re used to it in football too. Newcastle United was relegated in 2016 but, thankfully, promoted back in 2017. The tables show Newcastle University also back in the top 20 by 2017. Imagine, though, if the competition had been as great between universities as between football teams. How much more would this have spurred us on to regain our place in the top tier?

In the same year that it was getting ready to welcome new members, the Russell Group published a remarkably self-serving document. It members are “Jewels in the Country’s Crown”, it claimed, and thus “worthy” of government funding and protection. The same claim is repeated on its website today. The football Premier League is never short of money, and never goes cap in hand to government. Can’t universities stand on their own two feet, too?

Big money in football comes from television rights and betting. People are interested in who is winning and who is losing. The popular BBC television show University Challenge has viewing figures of 2.5 million: not a million miles away from the corporation’s football highlights programme, Match of the Day, which has 3.9 million. Tempting for advertisers, University Challenge is the show that is watched by the nation’s richest people. Perhaps Sky TV, which pinched most of the rights for live football from the terrestrial stations 25 years ago, should poach University Challenge, too.

Creative minds could surely come up with a combination of Match of the Day and University Challenge to entice viewers, showing pairs of universities battling for position in the league tables each week, urged on by irate and overpaid vice-chancellors snarling at each other on the touchline as the crowds bait them with chants of “you’re getting sacked in the morning”. It could be quite a lucrative spectacle – although I fear it might generate tension over the festive period as families elect whether to attend Boxing Day football matches or cheer on their preferred university.

There’s one elephant in the room. The Russell Group prides itself on containing the UK’s leading universities. The league tables don’t quite agree. The top 20 Russell Group universities are actually spread across the top 40 of the Good University Guide tables, with some non-members riding very high. In the latest edition of the ranking, these include St Andrews (3rd), Lancaster (6th), Loughborough (joint 7th) and Lord Adonis’ team, Bath (12th).

These institutions also used to belong to the 1994 Group, which was set up by smaller research-intensives as a competitor to the Russell Group, but was disbanded shortly after the aforementioned gang-of-four abandoned it. If the Russell Group really wants to be the universities’ Premier League, it will have to become a genuine meritocracy.

Another problem is that there is, of course, more than one league table available, so universities would have to settle on one. But once they’d done so, the fun could truly begin. And even if, post-Brexit, British universities are banned from European research competitions – as English teams were banned from European football tournaments in the wake of the Heysel Stadium disaster – the television and gambling rights would ensure that the funding kept flowing.

The English football Premier League is known to be the best in the world. With real competition, the same could be expected of the British University Premier League too.

James Tooley is professor of education policy at Newcastle University.

后记

Print headline: Play badly? Get the boot