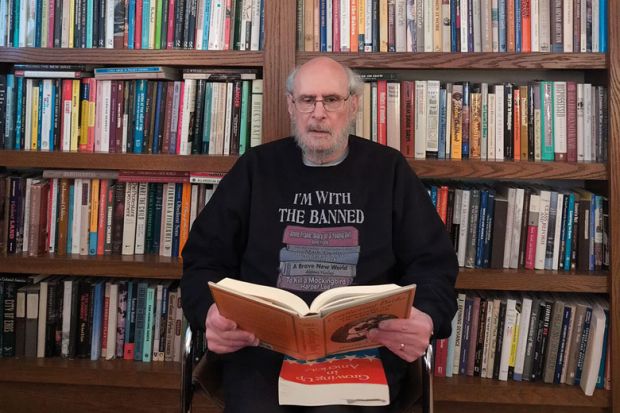

I suffer from an extreme case of a condition that afflicts many older professors, especially in the arts and humanities. Let’s call it bookitis.

As a child of the 1960s, when print was cheap and digital alternatives weren’t yet invented, I’m of a generation particularly prone to the excessive buildup of weighty tomes in house and office, blocking circulatory arteries and corrupting structures.

With new paperbacks costing less than a dollar and hardcovers less than $5, it was common for the academically minded to start building up substantial libraries very early in life. That process accelerated at university, where it was not unusual for history, literature and philosophy courses to require eight or 10 books, and sociology and anthropology five or six. Even formal textbooks, which cost today’s undergraduates hundreds of dollars, could be as little as $10 – although that didn’t stop us feeling aggrieved and occasionally shoplifting them.

My own bookitis was exacerbated by my multiple fields of study, which began in secondary school and continued beyond graduate school and into a first tenure-track position at a pseudo-interdisciplinary new university, where I had affiliations in both arts and humanities and social sciences.

The by now enormous weight of my library actually damaged the foundations of the first house my wife and I bought together. In later moves we checked with the construction inspectors before asking our contractors to build the bookcases. But structural concerns were far outweighed by the 25 to 40 per cent authors’ discount offered by the publishers of my early books, which prompted me to buy the more expensive (and heavier) items in their catalogues. The cumulative result was a personal professional library of more than 35,000 books when I retired.

For several years, I was unable to contemplate their redistribution: either the scope of the task or the prospect of seeing walls shorn of the decoration and soundproofing of scholarly knowledge. When I did finally adjust to retirement and began thinking about downsizing, the first item on my agenda was the almost 100 boxes of books in our basement, which had formerly lined my large university office but which I had no room to reshelve. Yet finding a new home for them was harder than I expected.

Several decades ago, university libraries would have lined up to accept what was almost a curated collection of books relating to literacy and its correlates. But no more. Limits of space and staffing, the spread of digital alternatives, and common rules restricting libraries to a single copy of each book meant that neither my own large public university, nor a nearby liberal arts college, nor the closest historically black university could accept my offer.

Eventually, however, the Books4Cause non-profit organisation agreed to take about 80 boxes (much to the displeasure of their truck driver), whose contents now reside in university libraries in Uganda.

Then I decided to go through my collection to decide what to keep when we do downsize. That was a real trip down memory lane, but, to my pleasant surprise, the “keep” pile was only 4,000 to 5,000 volumes high.

That led to a third step: seeking out “foster parents” for the 30,000 books I don’t want. I had begun doing some of this already, such as passing on books about the history of children and childhood to a young friend who studies girlhood in the British Empire. But last Christmas my targeted giving somewhat spontaneously accelerated and developed into an active plan.

During lunch with a former doctoral student who is now a professor in a local community college, I asked if he and his male partner would like two boxes of the best gay and lesbian histories and studies. He immediately accepted. What they don’t keep, they will give to LGBTQ young people’s groups.

The next day, I had brunch with a former undergraduate who was in town visiting his family. Now an MD, he happily took two boxes of medical history back to Maryland.

Other opportunities followed. Over dinner with two cancer researchers from the medical school, we discussed discrimination against women in science and outlined an interdisciplinary course one of them could teach on the history of women in science and medicine. I returned home and sent her two large boxes of relevant books.

A fellow historian writing what will become a landmark book on the history of child murders happily took a bag of books from my history of children collection. Another, an environmental and Southern US historian, has two boxes on ecological history and studies; my general American books await his review. Friends in early modern literature will take relevant social and cultural histories. A large number of books in 18th- and 19th-century British history await another colleague. And, contradicting the handwringing about young people with no interest in books, my undergraduate friends eagerly accept any print matter near their wide interests.

I recommend such targeted giving to other “old professors”. It is enormously stimulating. The relationships are mutually transformative: another form of ongoing teaching and learning. And although books will always remain close to my heart and mind, this bypass operation is necessary to prepare me for the next healthy phase of life.

Harvey J. Graff is professor emeritus of English and history at Ohio State University. He is currently writing Reconstructing the New ‘Uni-versity’ from the Ashes of the ‘Multi- and Mega-versity’.