France’s complicated and bureaucratic higher-education system has long been considered ripe for reform – not least because French universities have lacked international visibility.

The case was reiterated in 2009’s landmark Investing For The Future report, written by former prime ministers Alain Juppé and Michel Rocard. The resulting French Future Investments Programme (PIA) launched the following year. Its flagship €10.3 billion Initiatives d’Excellence (Idex) programme focused on comprehensive research-intensives, while the iSITE programme funded regional universities with international recognition in specific research fields.

I was a member of the international panel that judged applicants for Idex and ISITE status on the strength of their governance, research, training, innovation, international relations, partnerships and student life. Those selected were awarded an endowment for a probationary four years, after which their status was confirmed – or withdrawn – by the committee.

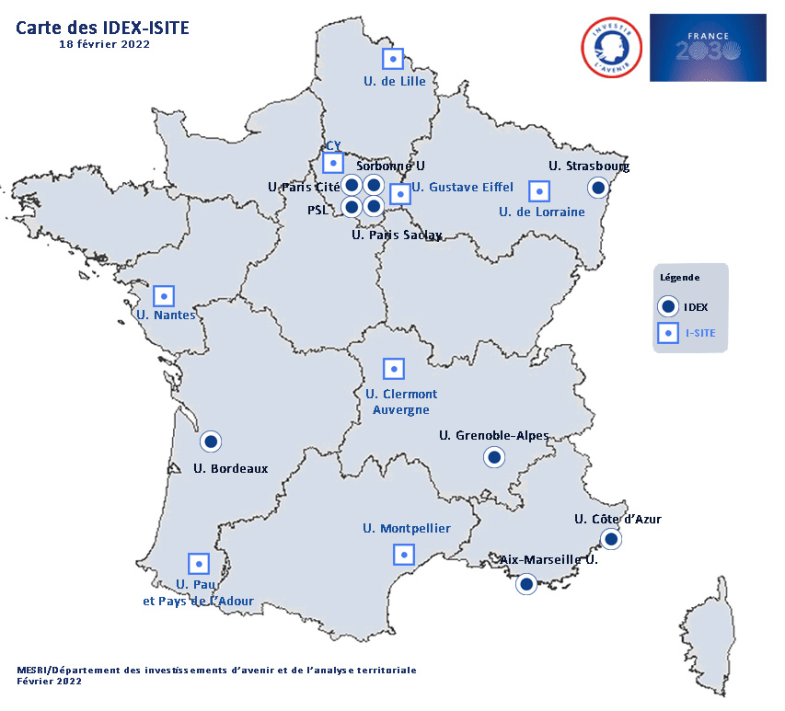

These programmes, alongside associated legislative adjustments, has prompted the amalgamation of various existing higher education and research institutions into new universities, such as PSL Research University Paris. Our recommended final list of 17 new and reconfigured universities – nine Idex and eight iSITE – has just been signed off by the French government.

Most of these institutions now appear in international university rankings, with several in the top 200. And despite declining French research output, further advances – and greater service to the nation – are possible if the government implements a funding model based on rigorous review that guarantees autonomy and supports ambition.

Key issues require special attention. First, peer review and innovative tenure-track processes are needed to improve governance and attract the most competent and ambitious staff. So far – in contrast to the norm at the world’s best universities – only one Idex university has dared to entrust its board presidency to someone from outside academia.

Secondly, while some of the prestigious grandes écoles – created in the 18th and 19th centuries to educate engineers, teachers and leaders of government and industry – have willingly aligned with Idex universities (even using them to broaden their enrolments), others have resisted, in fear of losing their national brands.

This stance is misguided: excellence needs to be cross-fertilised between disciplines. But it has often been supported by parents, alumni and even, tacitly, by the ministries to which some grandes écoles are attached (such as agriculture, culture, defence and economy). Hence, some of these schools might integrate into larger university systems deliberately slowly, while others could self-eject unless there is sustained pressure on the new universities to move to an efficient governance structure.

National research organisations (NROs) – including the largest, CNRS – are also involved in the new alignments. This makes large bodies of full-time researchers and infrastructure available to specific universities. But while the universities define the contracts and enjoy medium-term stability of funding, the NROs continue to manage employment, including moves between different laboratories. The NROs cannot be held accountable by the universities and continue to define their own policies and identities, to the extent that they tend to celebrate only their own researchers’ success. The future success of Idex will require the role of the NROs to be rethought.

There is also an issue with France’s overall higher education landscape. Beyond the Idex/iSITE 17, French universities must find their place by developing different specialisms, such as specific research areas, vocational training, or regional economic and social contributions.

The PIA programme incorporates a range of initiatives aiming to enhance equipment, graduate schools and hospitals at all universities. Moreover, supporters insist that PIA’s dissemination of innovation and best practice in teaching and governance, combined with the competitive dynamic it sustains, will improve the entire system. Critics, though, fear that France has created a two-speed system that contravenes the principle of equal access to education. These political tensions will need to be managed.

Finally, French higher education requires a major simplification of the panoply of poorly coordinated supervision and funding streams arriving from different ministries and NROs. This complexity often hinders French universities’ decision-making, agility and international attractiveness. In today's higher education environment, where international mobility and excellence is the main driving force for student enrolment, consolidation must not be overlooked.

John Ludden is professor of environmental governance and diplomacy at Heriot-Watt University. Previously, he was director of research in earth sciences at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris and then chief executive of the British Geological Survey.