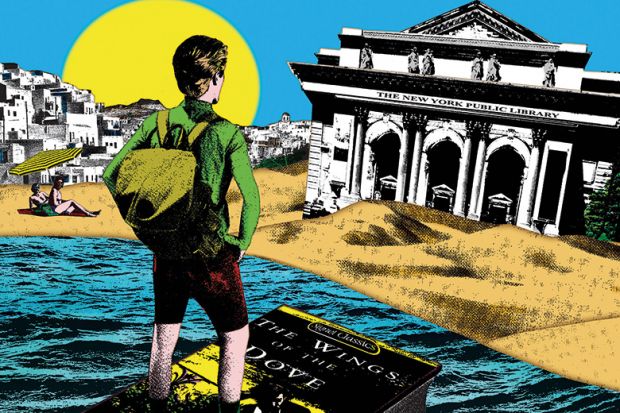

Weeding my books recently, I picked up a paperback edition of The Wings of the Dove that had somehow evaded earlier purges. I opened it aimlessly, as one does with any book in ones’ hands. The glue binding snapped, and out from the middle pages, dribbled a small stream of golden sand. My Proustian madeleine moment.

It was 1967. Greece. Retsina. Bread, feta and tomatoes. Love under warm canvas. And late-phase Henry James. Those wonderful rolling sentences. How does the narrative of Wings begin? She waited, Kate Croy, for her father to come in, but he kept her unconscionably, and there were moments at which she showed herself, in the glass over the mantel, a face positively pale with the irritation that had brought her to the point of going away without sight of him.

I remember my edition well. It was bought from the hippy Jim Haynes’ bookshop, off George Square in Edinburgh. A huge rhinoceros head over the door welcomed the fraternal customer in and kept the Morningside bourgeoisie out.

It was a Signet paperback. I scooped up half a dozen Henry James titles before embarking that summer, in my (Scottish-built, wholly unreliable) Hillman Imp for the Aegean. Bliss it was to be young, partnered and hopeful, in a university environment itself flowering in post-Robbins expansion and what they called “new maps of learning”.

At this time of year, as the sands run out everywhere, I remember “the long vac”, as it was then called; I think they now call it the “research term”.

My serious topic in that period was William Makepeace Thackeray’s manuscript remains. I wanted to touch what he had touched. You could do it then, without wearing latex gloves, like a Crime Scene Investigation technician. Thackeray had been hugely popular in the US and had made two remunerative lecture tours there. Unlike Dickens, he loved the country (read it in The Virginians).

Americans collected bits and pieces of him voraciously. His manuscripts, as a result, are disjecta membra, scattered in collections all over the US. The next long vac, 1968, I went, now married, in search of them. There was no internet catalogue and the National Register of Archives did not have American listings. One was a scholar adventurer, travelling light. It felt good.

Grant-funded, I spent three months in New York. The city boiled. But almost every day I found new Thackerayana. My happiest hunting ground was the New York Public Library.

This was the low point of Times Square moral squalor. There were porn shops and sleazy movie houses along 42nd Street. Bryant Square was the hangout of pushers, users, crooks, hookers and midnight cowboys – the big film that year. Inside the library, there were no doors on the cubicles in the mens’ restroom – to discourage shooting up and sex. Excretion was permitted – if you had the nerve.

Behind a formidably grilled door, was one of my favourite collections, the Arents. It specialised (still does, I believe) in literature with tobacco associations. Thackeray loved his cheroot and a quotation from The Virginians was immortalised on the Victorian Three Castles cigarette packet. I haven’t looked recently, but there is probably a health warning posted on the Arents’ door nowadays.

The other Thackerayan mother lode was the Pierpont Morgan, a few streets down Madison Avenue. It contained the jewel in the crown: the surviving Vanity Fair manuscripts. The “Morgan” is now the site of Manhattan’s finest tea room, but in its days as a dusty research library you went to the nearest greasy spoon if you needed a coffee. The brownstone building breathed old money.

This was the period when E. L. Doctorow was thinking of using it as the site of a revolutionary shoot-out between white plutocracy and black radicalism. Is there a better American novel of the late 20th century than Ragtime? I don’t think so.

I had no political quarrel with the place in 1968. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. Every night, my eyes blistered with reading old handwriting, I would buy two quart bottles of Bud from the nearby convenience store, hightail it back to the hotel room, put the beer in the sink to keep cool, tear off my shirt and write up the day’s finding. Then to Tad’s or wherever for a budget-price steak supper.

I got my Thackeray book – my first on research – largely done that summer in New York. I’ve never written anything about Henry James. But I experienced his fiction most fully that previous summer, on the sands of Greece.

When I peek over the fence at them, universities strike me as more efficient nowadays. I suspect that the sheer fun I had in those long-gone long vacs is a thing of the past. But so am I a thing of the past.

I think I’ll keep that Signet volume.

John Sutherland is emeritus Lord Northcliffe professor of modern English literature at University College London. His latest monograph, Orwell’s Nose: A Pathological Biography, is published by Reaktion Books.