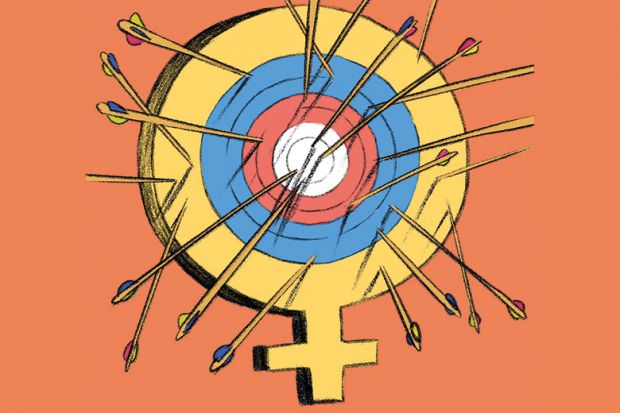

Last week’s dramatic downfall of the UK’s highest paid vice-chancellor, the University of Bath’s Dame Glynis Breakwell, offers a pretext for multiple reflections. These include the role of vice-chancellors as leaders of institutions devoted, after all, to learning and research, rather than corporate business. Another is how a salary of £468,000 looks when set against the declining real-terms value of general academic salaries and tripled tuition fees for students. But there is also perhaps a space to consider the gender question.

The term “nasty woman” became infamous in connection with an exchange between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential campaign, and it provoked a massive solidarity response on the part of women globally. This patronising use of language that assumed Clinton’s gender to be a marker of inferiority confirmed Trump’s non-reformed misogynist persona, already projected by multiple scandals.

Breakwell is no Clinton but she did attract a fair number of attacks, led by Lord Adonis. He has rejected any suggestion that his mission to topple her was gender-related. Nonetheless, just before her resignation, 15 senior female academics from the University of Bath signed a letter asking for a halt to the personal attacks on Breakwell, which, they feel, are indeed linked to her gender. They praised the university’s progress during her 16-year tenure and acknowledged the leadership that she provided. On the other hand, her former deputy, George Lunt, told the Bath Chronicle that “personal gain and personal ambition” had “got in the way” of Breakwell’s leadership. Criticism continues over the fact that she will earn an additional £700,000 before her announced retirement, and other dark rumours are circulating about her conduct in office. In short, the popular narrative goes, she had to go because she is a nasty woman.

Culturally, the “nasty woman” is a familiar trope. She has many guises in history, myth and storytelling, not necessarily just those familiar in Western culture. Simplifying the matter a little, there are, in essence, two kinds of nasty woman: the older, witch-like figure with no sexual allure, and the young seductress who gains her power through her sexual association with a man.

It is interesting to consider that while the Breakwell drama was unfolding in the UK, another powerful woman in a different part of the world was also being vilified and ultimately brought low. I am talking, of course, about Grace Mugabe, Zimbabwe's former first lady, who moved to take power directly for herself as the 37-year presidency of her ailing 93-year-old husband, Robert Mugabe, drew towards its inevitable conclusion.

To begin with, Grace’s power was clearly located in her sexual attractiveness. The Zimbabwean president famously plucked her out of the typing pool while he was still married to his first wife, Sally, who was very unwell. Grace was indeed the power behind the throne and was deeply unpopular within Zimbabwe even before she started adopting a more public persona as she eyed the throne for herself.

A talented public speaker, she clearly began to enjoy her apparent command of the crowds. But her public addresses were seen as too ambitious, and even bullying. As she occupied the liminal space between the aged wise woman and the sexually alluring temptress, astonishing stories began to circulate of her allegedly insatiable sexual appetite and her physical violence towards her entourage, journalists and her sons’ girlfriends. Some of these were confirmed with photographs and reported widely.

However, as a researcher who has made frequent visits to Zimbabwe over the years, I would still argue that the extraordinary hatred of which she became a focus related to her gender as much as to her actions. Unfortunately, she also alienated the women around her – those who could and should have been her new power base – with a variety of ill-judged public comments, including the infamous one arguing that victims of rape were “asking for it” because of their outfits or make-up. In the end, she became the symbol of corruption, while her husband is still thought of as a liberation hero, confused by his “nasty woman” wife. This is despite his many serious human rights abuses committed a long time before Grace came on the scene.

Breakwell and Grace Mugabe have very little in common. But their downfalls illustrate two things. First, that unconscious gender bias against powerful women is still a fact across cultures. Second, that gender does not protect anyone against the dark allures of power – especially, in Breakwell's case, in the context of an academy that is becoming more of a corporation than a place of support and inspiration. A colleague at the University of Bath wondered why Breakwell couldn’t “just have been…well, nicer? More collegiate? Less blatantly money-grabbing... Let me tell you, this has become a horrible place to work”.

That may well all be true. But there are overpaid and unloved men running British universities, too. Nasty men. Would they have been subjected to quite the same degree of opprobrium?

Agnieszka Piotrowska is reader in film practice and theory at the University of Bedfordshire. She is author of Black and White: Cinema, Politics and the Arts in Zimbabwe. Her latest book, Nasty Woman and the Neo Femme Fatale in Contemporary Cinema, will be published next year by Routledge.

后记

Print headline: Through jaundiced eyes