Brian McNeil hasn’t been able to hold down a steady job for more than 30 years. Over the past two decades, he has signed about 40 employment contracts, none lasting more than four months. At one point, he worked three jobs just to make ends meet – and most summers he spends several weeks on the dole.

His vocation? University teacher. For the past 20 years, he has worked on and off as an affiliated faculty member at Emerson College in Boston – a private university that specialises in the arts and charges about $46,000 (£34,000) annually for tuition.

McNeil’s situation is not unusual in US academia. He is part of a growing body of part-time, temporary teaching staff who are routinely hired, fired and, if they’re lucky, rehired – often to free up more research time for the lucky minority of academics who have tenure.

“It’s become like academic apartheid, where affiliated or adjunct faculty are seen as second-class academics,” says McNeil, who specialises in film, photography, painting and sculpture.

He adds that the situation has a knock-on effect on students, because temporary staff tend to be on campus only on those days when they teach, and so are less available to answer queries.

Although McNeil is 67 years old, there is no chance of his retiring soon; without a university pension, he cannot afford to stop working.

“I’ll probably teach until I die, right [here] in the classroom,” he says.

Nor is that remark necessarily a rhetorical flourish. In 2013, Margaret Mary Vojtko died at the age of 83 while still working as an adjunct faculty member at Duquesne University in Pennsylvania. A column written by a member of the United Steelworkers union in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette after her death reported that she was underpaid, underappreciated and nearly destitute when she died.

This sense of being undervalued is common among temporary staff. An adjunct member of an English department in California, who has been a university teacher for six years and wishes to remain anonymous, tells Times Higher Education that people like her are undervalued by both students, “who often take your class for granted”, and administrators, who see you as “a member of a body of people that has constantly asked for more money [that university managers] don’t want to give”.

She is currently teaching a summer class, but she would earn more money if she received unemployment insurance, she says. To add insult to injury, she was recently the victim of “bumping”: she lost a class that she had been told she would teach because it was reallocated to a new full-time member of staff. She was particularly vexed that the university did not alert its “part-time labour pool” to the unadvertised vacancy; this brought home to her that she is “not appreciated here”.

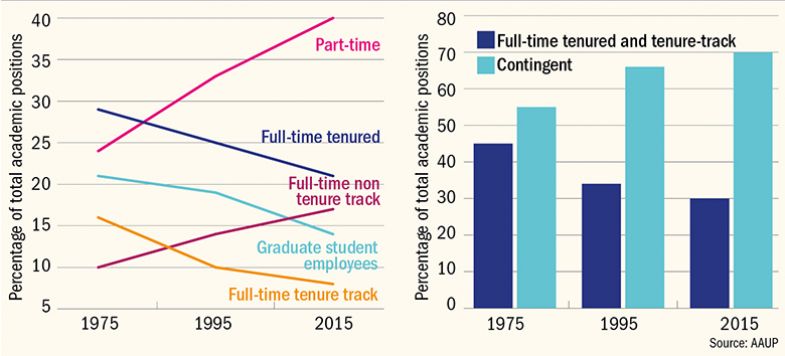

Unsteady work: US employment trends

Figures from the US Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, compiled by the American Association of University Professors last year, show that the proportion of the US academic workforce made up of part-time faculty increased from 24 per cent in 1975 to 40 per cent in 2015. The share of full-time non-tenure-track academics also shot up, from 10 per cent to 17 per cent, over that period (see graphs, above).

Meanwhile, the proportion of full-time tenured scholars dropped from 29 per cent to 21 per cent, and the share of full-time tenure-track faculty halved, falling from 16 per cent to 8 per cent. Joseph Roy, senior researcher at the AAUP, notes that these trends have accelerated since the start of the recession in 2008. Moreover, an AAUP report published in 2010, Tenure and teaching-intensive appointments, notes that “the majority of teaching-intensive positions have been shunted outside of the tenure system”, leading to “a [teaching] faculty with attenuated relationships to campus and disciplinary peers”.

Richard Chait, emeritus professor of education at Harvard University, says that the reduction in the proportion of US academics on the tenure line has been “gradual enough to be imperceptible at any one moment, but, over time, it’s really been a remarkable change”. He likens tenured academics to federal judges, “who also enjoy lifetime appointments”. They “have the security to pursue their research in a defensible, reasoned scientific fashion without worry that they are conducting lines of enquiry that might be viewed as unpopular. The circumstances under which a tenured faculty can be removed are quite stringent, and it’s a very rare occurrence.”

In contrast, he says, adjunct faculty are “almost an academic version of migrant labour” in light of the widespread “disregard” for their work and their “insecurity, transient positions [and] comparatively low wages for what are deemed to be the less desirable assignments”.

The rise of what is often referred to as “precarity” in higher education is by no means confined to the US. The estimated share of “casual” staff in Australia increased from 15 per cent in 2008 to 18 per cent in 2017, while the proportion of full-time staff fell from 74 per cent to 70 per cent, according to data from the Department of Education and Training.

Minnie Li, a contract academic at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who is approaching the end of a one-year, non-renewable teaching contract, says that Hong Kong universities’ obsession with improving research performance, driven in part by their focus on research-focused rankings, means that teaching positions now tend to be insecure and undervalued there, too – although figures suggest that part-time and short-term contracts have not increased as a proportion of all academic positions in the territory, hovering at about 15 per cent since 2009.

Meanwhile, data from the Federal Statistical Office in Germany reveal that the number of university lecturers (a temporary position) has doubled to almost 100,000 since 2005. In comparison, there are about 50,000 professors in the country and their number only grew by 3.6 per cent between 2014 and 2017, compared with 5 per cent for all full-time academic staff, according to official figures. Last year’s University Barometer survey, carried out by the Stifterverband thinktank and the Heinz-Nixdorf Foundation, found that 63 per cent of academics at Germany’s state universities have fixed-term contracts.

Michele Gazzola, an Italian-born researcher at the University of Leipzig, has signed 13 temporary contracts at universities in Germany, Switzerland and Slovenia over the past seven years. He notes that in Germany, there are very few permanent academic contracts below the level of professor. And while German law stipulates that universities must typically transfer staff on to a permanent contract if they have worked part-time for 12 years, this does not apply to academics who work on projects funded by third parties. An article published in the journal Forschung & Lehre (Research & Teaching) earlier this year says that half of German universities’ budgets are now financed by temporary funds, such as third-party research grants.

Gazzola cites three reasons for job insecurity among junior academics in continental Europe: the underfunding of universities, the huge supply of PhD students and postdoctoral researchers and the very high level of job security for full professors, who “cannot be fired”. While Italy caps the number of doctoral students universities can enrol, elsewhere assistant and associate professors are incentivised to supervise PhD students and hire postdoctoral researchers, resulting in a glut in junior academics with little chance of securing a permanent position.

That situation appears to be particularly acute in Brazil. According to Kai Michael Kenkel, associate professor in the Institute of International Relations at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), Dilma Rousseff’s government of 2011-16 invested in postgraduate education, resulting in a “significant spike” in the number of new doctoral programmes and PhD enrolments. However, Brazil’s current government has “absolutely gutted education”, cutting the budget for public universities by “about 90 per cent for research and day-to-day operations”. Hence, there is now less demand for the new PhD graduates, meaning that there are “more people on the market having to get by on adjunct positions”.

Salt was rubbed into the wound, according to Kenkel, by a watering-down of the law regarding collective bargaining agreements, prompting some large private universities in Brazil to fire all their adjunct staff and require them to sign new contracts, with less favourable conditions, if they wanted to continue to work.

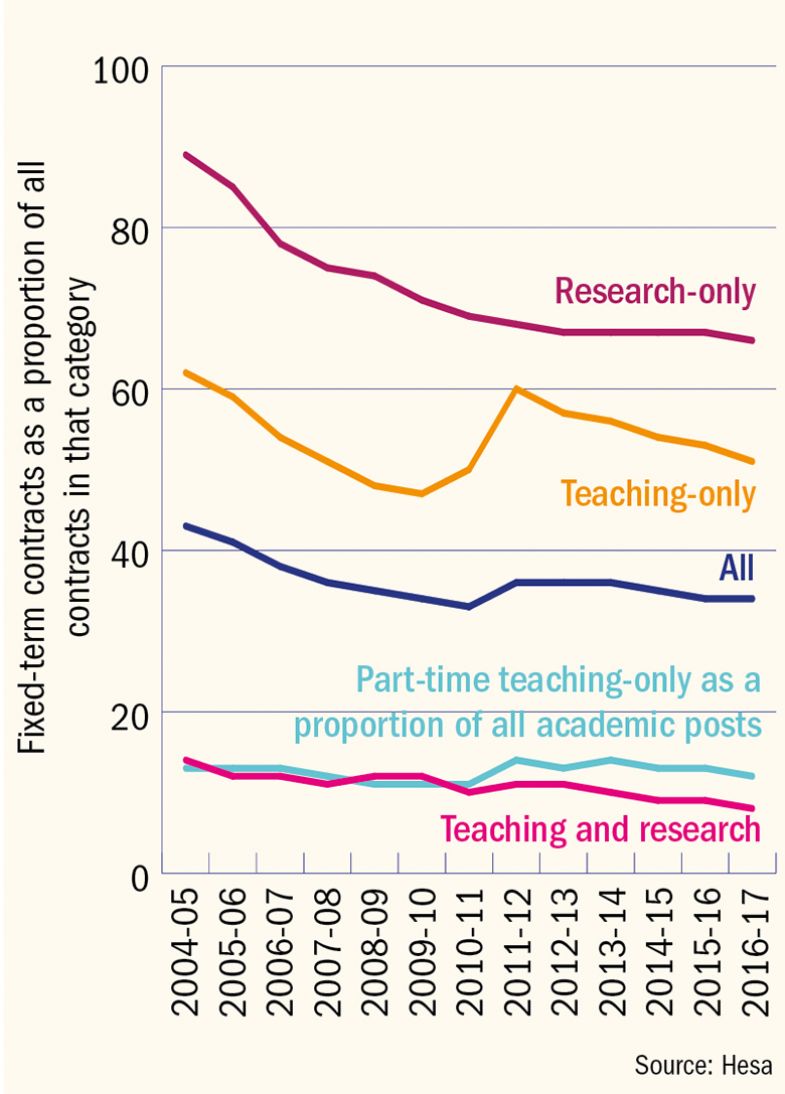

Concern is frequently voiced in the UK, too, about casualisation. But while the Higher Education Statistics Agency was unable to provide long-term figures, the most recent data suggest that the number of fixed-term contracts in the UK has actually been on a slightly downward trajectory over the past decade. Across all contract types, fixed-term posts declined from 43 per cent of all posts in 2004-05 to 34 per cent in 2016-17, according to Hesa. The fixed-term share of teaching-only contracts fell from 62 per cent to 51 per cent over the same period, while the number of part-time fixed-term teaching posts as a proportion of all academic positions held steady, at about 12 per cent.

But Steven Parfitt, a teaching fellow in history at the University of Loughborough, who is on a nine-month contract, still thinks those figures are too high, and he doesn’t buy the argument that UK universities rely on temporary staff because funding is scarce.

“It’s difficult to take the plea that they don’t have enough money seriously when you look at the enormous building programmes that are going on at all of these universities,” he says.

Last year, Parfitt earned just £10,000, despite working a full-time schedule by combining part-time contracts at three different universities.

Emerson’s McNeil is sceptical about the underfunding argument as well, observing that the high number of adjunct faculty in the US seems to be at odds with the high tuition fees many institutions charge.

“It’s like the Jews say: ‘What am I? Chopped liver?’ In universities, the very smallest amount of pie goes to faculty and then an even smaller amount goes towards part-time faculty.”

McNeil’s case aptly illustrates that not all casual staff are young, but because the majority are, the issue of casualisation is often exacerbated by a lingering sense of intergenerational injustice – particularly given a common perception that senior academics are sometimes held to a lower standard than their would-be replacements. An Italian lecturer based in the UK, for instance, tells THE that, in her view, there should be “less security” for senior academics in Italy, who can currently get away with publishing few papers.

Going down: UK’s campus casuals

In the US, an increasing share of university budgets went towards paying geriatric faculty after the country abolished mandatory retirement ages in 1986. That was delayed until 1994 for universities, but Ronald Ehrenberg, Irving M. Ives professor of industrial and labour relations and economics at Cornell University, says that his efforts to persuade presidents of major universities to lobby for a permanent exception for higher education were rebuffed. “Their response was that Congress feels that higher education already is getting special treatment, and they’re not interested in giving us more,” he says.

As a result, it is now “very difficult” for universities to “diversify the faculty across fields of study as demand changes, as student interest changes and as new fields of study come about”, because it is not possible to replace older academics in unpopular disciplines with younger ones in those new fields.

“At my university, most of the faculty who stay on beyond age 70 are the best and the brightest, so it’s not that there’s a lot of dead wood around,” Ehrenberg says. “But it would be really nice if they understood that the wellbeing of the university requires a flow of new faculty coming in.” One solution, he says, would be for senior academics to assume emeritus status and continue working without pay.

Once again, Brazil offers an extreme example of intergenerational skew. There, public universities had historically paid retired staff their full salaries, according to Marcelo Knobel, rector of the State University of Campinas in São Paulo. While that arrangement has recently been scrapped, institutions are still obliged to fork out on scholars who retired before 2013, he says.

“The idea was that choosing to be a professor in a public university probably would mean that you receive a lower salary [compared with the private sector]; but on the other hand, you would have two extra things – the first one is the stability in your job because you are a public servant, and the second one would be the full salary after you retired,” he says. Given the recent funding cuts, almost 35 per cent of his university’s budget is now accounted for by payments to retired staff.

Back in the US, another problem is that even when senior tenured staff do eventually retire, they are increasingly replaced by contingent staff, sometimes in completely different departments.

“What [universities] learned was rather than make some big public formal confrontation and say ‘we’re going to abolish tenure’, they just quietly changed the positions as they came open. Or, if they opened new positions, they created them with the conditions that they wanted,” says John Thelin, professor of education at the University of Kentucky and author of the 2004 book A History of American Higher Education.

As an example, he says, many US universities have in the past 10 to 15 years created a new position that is typically called “lecturer” – this has a “reasonable salary and benefits” but also a “five-year limit”.

Harvard’s Chait believes that it would be better to limit tenure to 25 or 30 years in order to reduce the negative impact on flexibility and junior recruitment of the scrapping of mandatory retirement. Such a move would have to be decided on at institutional level because US universities’ charters guarantee them a high level of immunity from political diktat, and Chait acknowledges that “among the elite research universities, it would be quite a competitive disadvantage for any one of them to eliminate tenure…For the diehards, tenure is gospel and you can’t rewrite gospel without being blasphemous.”

But he has “never thought that it was absolutely essential to have a tenured faculty”, noting that “there are enough examples of researchers and teachers who have achieved great distinction without the benefit of tenure”.

The UK might well be a case in point. Bruce Macfarlane, professor of higher education at the University of Bristol, began his academic career in 1987, a year before Margaret Thatcher’s government abolished academic tenure. In his view, the move did not, in itself, have a great impact. “The shift in the expectations that now confront academics – both in terms of teaching and research – represent, in my view, a much bigger change,” he says. “The separation of research from teaching funding in the mid-1980s was the thing that has really changed what it means to be an academic in the UK today.”

The modern pressure to meet performance targets – with the threat of ultimately losing your job if you fail – means that Macfarlane “felt more secure” when he was a junior lecturer in the late 1980s than he does today as a full professor. And although the fact that even professors in the UK can be dismissed for underperformance might give hope to junior temporary lecturers pining for a vacancy on the next rung up the ladder, Macfarlane says that the rules for the 2021 research excellence framework, requiring all staff on contracts involving research to be entered, “will only encourage institutions to create more teaching-only positions, often on an inferior fixed-term basis”, to reduce their “REF risk”.

Cornell’s Ehrenberg is far from alone in believing that tenure is important because it “provides an incentive for senior faculty to fully share their knowledge with their junior faculty and their PhD systems” and to “work on behalf of the long-term well-being of the institution” because they “don’t have to worry about the younger scholars rising up and striking them down”.

So might senior academics’ extra job security make them more willing and afford them more freedom to lobby for improved conditions for their junior and untenured colleagues than they would otherwise be?

Such solidarity, it seems, is not always easy to find. According to Claire Polster, professor in the department of sociology and social studies at Canada’s University of Regina, there is a “surprising amount of silence” among her country’s tenured academics about the rise in precarity at lower academic levels. She attributes this to the “ongoing fragmentation and tiering of academic work in Canada”. There is not just a divide between precarious and full-time faculty, she says, but also between the latter and “a category of elite academics”: those funded by the Canada Research Chairs or Canada Excellence Research Chairs programmes, who have “a lot more money than regular academics, a lot more prestige, [and] a lot more power”.

She argues that this fragmentation means that the different groups of academics “look at one another as competitors – and that, in turn, helps to make them more vulnerable to administrations”.

So what about self-help among temporary staff? About 2,000 casual academics and teaching and research assistants at York University in Toronto went on strike for almost five months until 25 July in protest against job insecurity (another 1,000 were on strike for almost four months). According to the Canadian Union of Public Employees, the number of casual academics at the institution has ballooned by 121 per cent since 2000, while the number of tenured professors has risen by just 20 per cent over the same period.

Last week, the Ontario government passed legislation ordering the striking academic staff to return to work, ending what is believed to be the longest-running university strike in Canadian history. The act claims that about 37,100 students were enrolled in at least one course that was unable to progress while the strike continued, and that some 45,000 students were missing grades that would have been available but for the dispute.

David Robinson, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, hopes that the strike will prompt a conversation across North America “about what’s happening in terms of employment at universities, what the impact is and how we can resolve it”.

“This, I think, is just a harbinger of things to come if we don’t resolve these issues,” he says.

Emerson’s McNeil believes that unionisation is key to improving job security for academics on precarious contracts. When he joined Emerson 20 years ago, he started one – with the result that all adjunct faculty received a pay rise of between 20 and 30 per cent. In addition, salaries for temporary staff are now stepped based on the number of courses they have taught, meaning that long-term adjuncts are rewarded the most.

But a temporary academic in the US who does not want to be named says that pay rises typically take “years to negotiate” and can lead to disappointing results.

“My union recently negotiated a 1 per cent pay rise after two years of mediation,” she says.

Loughborough’s Parfitt was “involved tangentially” with a campaign at the University of Nottingham to increase salaries for low-paid employees, such as cleaners, caterers and security guards, to the level of the nominal “living wage”.

“Comparing the building programmes at Nottingham with the amount of money it would take to give them the living wage, you got a sense of the small sums involved in [the latter] and the enormous sums in [the former],” he says.

In the case of casual academic staff, he argues that universities could make a start in improving their conditions by ensuring that such staff get paid for all the hours they work, rather than just those they teach.

“It seems like a no-brainer, but, in fact, that doesn’t generally happen for most casual workers at university. They tend to work more hours than they get paid for, and they do that because if they don’t do that extra work the danger is they won’t get rehired and their chances of getting a full-time job will be lessened,” he says.

But Regina’s Polster cautions that in seeking to improve adjunct staff’s working conditions, “we need to be careful not to institutionalise precarious work”. Conversion programmes that provide opportunities for long-time temporary faculty to switch to full-time contracts would be a bigger step in the right direction, she says.

“That, to me, is the better idea: to recompose academic work rather than having an institutionalised tier of inferior labour,” she says. “No matter how much more pay [temporary staff] get, it is still not the same kind of work [as permanent staff do], with the same kinds of responsibilities and expectations of teaching, research and service.”

后记

Print headline: Don’t get comfortable