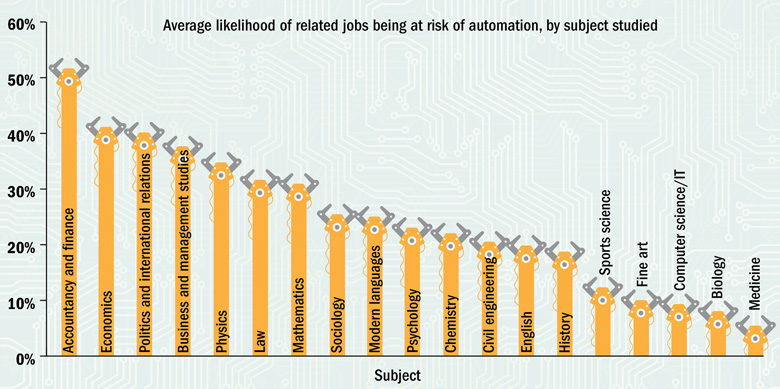

Students of accountancy and finance are at most risk of having their future jobs taken by computers and robots, while medics are likely to enter occupations at least risk of automation, a Times Higher Education analysis has revealed.

Amid growing concern that machines are replacing humans in the workplace, prospective applicants may be wondering whether their chosen discipline will lead to obsolescence.

The analysis of the most popular subjects in the UK is based on the work of Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, academics at the University of Oxford, who in 2013 developed a ranking of jobs by how likely they were to be automated in the next 20 years.

Their calculations – which considered factors including whether jobs required skills such as creativity and social intelligence that, so far, are beyond robots’ capabilities – found that 47 per cent of jobs in the US were “at risk” of automation.

THE used these data (which had been adapted for the UK by the BBC) to see which subjects lead to jobs most in danger of automation, using a database from the Prospects careers website, which lists whether a degree course is “directly related to” or “useful” for a particular job.

The results reveal dramatic differences between subjects. Accountancy and finance is particularly vulnerable because directly related jobs such as accountant, taxation expert and financial technician are judged to have at least a 95 per cent chance of automation.

Medics are much safer, with just a 2 per cent chance that medical practitioners will be automated, and other related careers such as scientist and health services manager are also resistant to machine encroachment.

Jobs in IT and programming are considered to be reasonably safe, making computer science and IT one of the least automatable areas.

Which degrees offer the prospect of a future?

Solicitors, management consultants, journalists, public relations workers and secondary school teachers are also seen as relatively immune from automation, meaning that English and history generally seem a better bet than the sciences.

Sports science and biology jobs are also seen as less automatable because occupations related to health generally have a low automatability likelihood.

Not all jobs on the Prospects website matched up with the Frey and Osborne data, while some subjects led to occupations with very different prospects. Physics graduates going into metallurgy have at least an 80 per cent chance of being at risk, but those opting for careers in science, business analysis and teaching are likely to be far safer.

The most at-risk jobs are typically low-skilled ones. Call centre salespeople, typists, clerks, administrators and receptionists all have at least a 95 per cent chance of becoming at risk from machine replacement, according to the data.

But a book released in October last year, The Future of the Professions, argued that even relatively highly skilled jobs such as doctors and lawyers could be replaced by increasingly capable machines.

One of the authors, Daniel Susskind, a lecturer in economics at the University of Oxford, told THE that to avoid obsolescence, prospective students should join organisations that were “flexible” and willing to change the nature of jobs as more areas became automated.

For example, “the sorts of things a nurse does today is very different from 25 years ago”, he said. Previously, they handled tasks such as bedside care and taking care of bedpans; now they can perform minor surgery.

As for subject areas, he advised students to “do things which machines as yet can’t do…machines are bad at interpersonal communication, empathy and problem-solving” and to steer clear of areas that involve “rote learning and vast amounts of information”.

后记

Print headline: Which career is safest from the march of the machines?