Source: James Fryer

Academic writing and critique have a tendency to incredulity, one-upmanship and acidity. As a result, academic discourse can be vicious and damaging

Most academics would agree that the guiding values for peer review should include objectivity, balance and fairness, leading to measured, constructive, critical discourse.

Yet all too often competitiveness and personal prejudice get in the way. This arguably causes many authors to be more cautious in their arguments and conclusions than they might have been if guaranteed fair treatment.

The desire to address this issue is behind a new movement in critical management studies, our specialist field. Our “experiment in critical friendship” will take place at the Critical Management Studies conference in Manchester next week and is based on some of the idealism that spawned the field in the first place.

Critical management studies is the analysis of existing management systems and the academic theories that legitimise them. The movement was born from attempts by thinkers to question the inequalities and oppression often found in such structures.

Under the terms of our experiment, any female scholar seeking feedback from other women can submit a working paper in advance of the conference; participants will then engage in constructive, friendly and supportive criticism at the event. Destructive criticism, of the type so common in academic discourse, will be banned. So too will hierarchy – anyone can pitch in. The discussion will be recorded and sent to the authors. We hope that this will not be the end of the process: authors will also be encouraged to continue to seek support for and feedback on their work via our website.

The experiment has been organised by Vida, an association set up in 2009 for women working in critical management studies and business schools. Vida means – depending on the context – “beloved friend” or “life”. Both meanings are appropriate to our organisation, which celebrates and enhances the rewards of academic life through friendship. The experiment builds on our work to develop the concept of the “critical friend”.

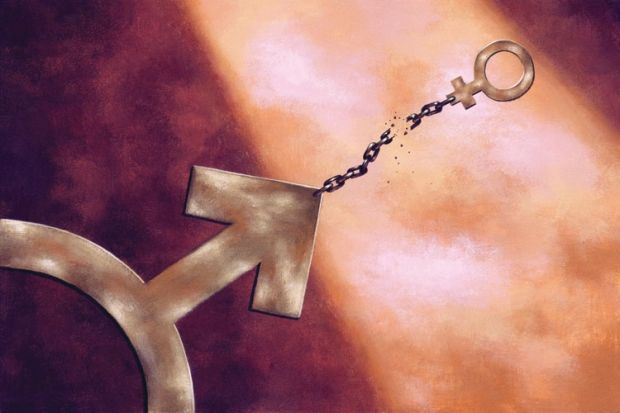

Why restrict the experiment to women? We are doing so because the contribution of female academics historically has been underplayed in our discipline and elsewhere: the lack of contemporary recognition for Rosalind Franklin’s part in identifying the structure of DNA is simply one of the more notable examples. To address this imbalance, women need the opportunity to strengthen and support each other.

Being a female academic can be a lonely and discouraging business in a field where – as in the rest of academia – the leading formal positions are usually held by men and the rules of engagement are set out along masculine, “my theory is bigger than yours” lines. Both academic writing and critique have a tendency to machismo, incredulity, one-upmanship and acidity.

As a result, academic discourse can be vicious and genuinely damaging, particularly in the case of peer reviewers with the benefit of anonymity. This can mean that left-field ideas are not developed into papers out of fear of outright dismissal and even open mockery. Brilliant female minds are not given enough space to develop in an environment where too often aggression is prized over originality.

Our experiment – and Vida more generally – aims to provide an antidote: encouraging and creating friendships among women.

Are we generalising unfairly about the attitude of male scholars? We have certainly been supported by male academics who do not take an excessively and unnecessarily combative approach in their relations with others. We, however, have been lucky. Too often the highly competitive academic system creates unsupportive senior men – and unsupportive senior women. Individual men and women treat their fellow academics well or badly, but the overall system is excessively masculine and this tends to corrupt both sexes.

To those who would argue that our experiment is just another talking shop, we say, what’s wrong with that? Bright women working in the same field will undoubtedly improve the quality of the work they do through talking about their ideas with each other. In academia, talk is the fuel that drives us.

We hope, moreover, that over time our approach will produce tangible outcomes, including better papers, lower failure rates for journal submissions, and a more intellectually varied and daring body of work in our discipline and others that choose to adopt it.

The short answer to why we are restricting the experiment to women is, why indeed? We call on fellow scholars across all disciplines to imitate our example and set up critical-friend networks. Let us make academia kinder, more caring, more egalitarian and more effective. Let us work to ensure that all scholars, no matter where they are employed or at what level, have equal visibility and equal voice so that they can pursue their research projects without feeling disenfranchised and silenced.