Although the threat to international student recruitment has been the most obvious financial challenge posed by the coronavirus pandemic for some countries, the crisis has shaken the foundations of university systems in all corners of the world, whatever funding models they employ.

Its long-term economic effects could lead to governments slashing spending on universities and research, while households and firms may also have less spare cash to spend on higher education.

However, the crisis will certainly not affect all regions of the world equally, due in part to the huge variations in the way Covid-19 has been tackled and also to the different underlying structures of each system.

So what global data can we examine to get a flavour of which countries may be most exposed to the crisis? And what is the likelihood that the pandemic will fundamentally alter the funding models previously relied on by universities?

Given it has been seen as the biggest short-term financial threat, the reliance that different countries had on international students before the pandemic began may be an obvious place to start.

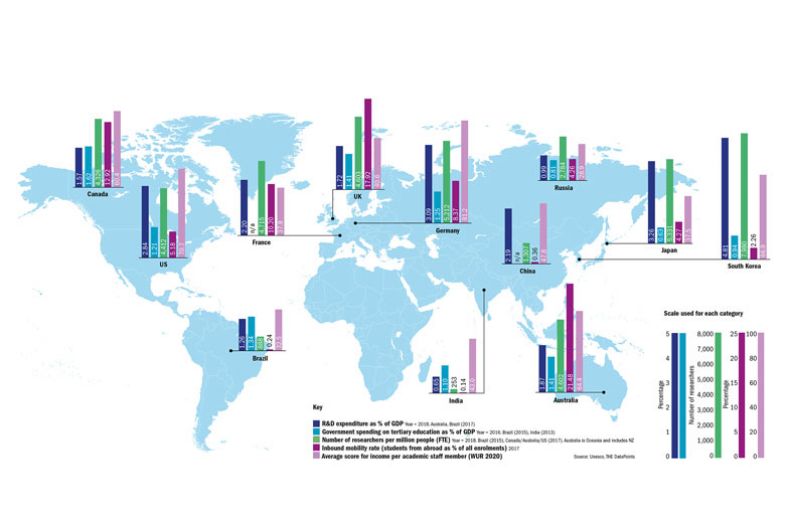

Data from Unesco showing the inbound flow of students as a share of that country’s overall enrolments reveal huge variations: in 2017 Australia’s inbound student population was 21 per cent of its total enrolments, while in the UK this inbound mobility rate was 18 per cent.

Both are nations where the hit to international recruitment has formed the basis of dire forecasts of financial struggles, given the fee income that overseas students bring to universities in both countries.

Other countries, such as France or Germany, also have relatively high inbound mobility rates, but may be less likely to suffer financial damage from a downturn due to the low or negligible fees their universities charge.

Meanwhile, another country where overseas students do pay high fees, the US, is not so reliant overall in terms of numbers, with about 5 per cent of all students coming from outside the country.

Still other nations – particularly in East Asia – have much lower dependence on incoming students and may even benefit from any shift in the coming years towards students seeking to study in their own region.

In light of that student mobility picture, how well funded from other sources were different countries before the pandemic?

Although the latest global data on public funding for tertiary education are a little older, Canada appears to be in a relatively better position here, with government money for the sector making up 1.6 per cent of gross domestic product.

Provided it can maintain such investment in the face of the economic downturn, it could potentially weather any hit to the international recruitment on which it does rely to an extent.

Other countries may not be so well placed on this score. For instance, US public investment in higher education was already low by international standards and there have been warnings that state funding could be hit hard by the pandemic.

However, it is also important to recognise that some countries, including the US, make up a lot of their investment in universities from private sources.

The statistics on overall research and development expenditure give a flavour of this, with the US joining countries such as South Korea, Japan and Germany where investment in innovation from companies helps to fuel higher education, too.

Data in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings on institutional income per academic staff member give a small indication of how all these different pieces of the funding jigsaw fit together for all these countries.

This shows that the highest ranked universities in some developed systems, like Germany, the US, South Korea and Australia, may be able to withstand significant financial damage to the system without resources dwindling. But there is clearly a risk for other nations, including the UK.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, said he was concerned that universities outside the research elite in the UK could be left to wither.

“If the bulk of the universities are seen to be in decline after the pandemic, in the long run that will undermine the UK’s position as an education exporter,” Professor Marginson said.

He added that while the US was “unlikely to arrest the decline in state-level public funding, it is better placed to recover in international education”, given there was room to expand and the potential for a political shift if Joe Biden wins the presidential election.

“I think a Biden government is likely to kick-start a revival of US international education, and increase research funding at the top end,” he said.

But it was in East Asia and parts of continental Europe where Professor Marginson saw the potential for the crisis to accelerate trends that were, to a degree, happening already.

Countries like China, South Korea and Japan “will be looking more attractive than before, relative to the Western countries, for international students”, while in Europe, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the Nordic countries “all have the opportunity to become globally bigger in higher and international education in the post-pandemic period”.

Jamil Salmi, former tertiary education coordinator for the World Bank, has looked at how Covid-19 is exposing structural deficiencies in higher education systems for a chapter in an upcoming book edited by the Council of Europe.

He stressed how it will be important for governments “to assess the vulnerability elements of each system: reliance on private funding sources, reliance on international students, reliance on private institutions, reliance on mortgage-type student loan systems, reliance on non-staff instructors, etc".

“These are the sources of weakness which need to be addressed to build long-term financial strength and resilience,” he said.

However, he said he was “not sure how many governments will undertake a comprehensive reflection to move towards a more sustainable funding of their higher education system”.

If such changes are not made, then it could be researcher numbers that suffer, with Unesco data already showing how some countries are in a healthier position than others in terms of this human capital.

Caroline Wagner, Milton & Roslyn Wolf chair in international affairs at Ohio State University, said her greatest concern “is for people and institutions that might have been on the margins of the system at the start of the pandemic”, including “young faculty/researchers who are finding it difficult to get jobs or continue their research”.

“Students may eventually get back on track as the pandemic ends, but the damage to young faculty – and those from developing countries – may be more difficult to repair. Some of them are already leaving academic life because of the strains and obstacles. This loss may be permanent,” she said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: Which systems are at most risk from the Covid financial fallout?