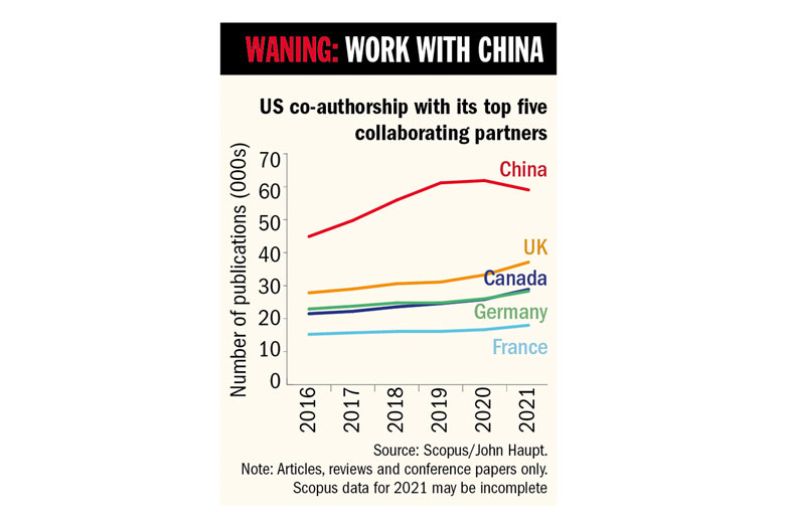

The rapid growth in research collaboration between the US and China appears to be tailing off, and may even have declined last year, with geopolitical tensions and Covid-19 both potential factors, according to latest data.

Data from the Scopus database of indexed research suggest that the increase in the number of publications involving both mainland China and US-based researchers slowed markedly in 2020 after several years of strong growth, while current figures for 2021 show a fall in co-publications.

Although some 2021 research is yet to be indexed in the database, “we did not see this decline in collaborations between the US and its other top collaborating countries and China and its other top collaborating countries”, said the University of Arizona’s John Haupt, who shared the data with Times Higher Education.

THE Campus resource: Eight ways your university can make research culture more open

The researcher at Arizona’s College of Education, who has been studying US-China collaboration patterns, said this indicated that “something unique” was happening with the two countries.

“We believe there are specific factors at play that have changed the trajectory of co-publications between the two countries, which for so long has been characterised by rapid growth,” he said.

Mr Haupt pointed to political tensions, with a national survey of scientists by Arizona researchers suggesting that scrutiny of researchers’ ties to China had “resulted in a reluctance in US-based scientists to collaborate with China-based scientists”.

Meanwhile, the pandemic’s travel restrictions had “impacted the traditional ways in which scientists interact and establish relationships”, with evidence of scholars limiting physical visits in both directions.

“These visits have traditionally provided them with opportunities to meet scientists who have similar research interests and maintain or establish collaborative ties,” said Mr Haupt.

However, he added, even if it could be shown statistically that these trends might be having an impact on co-publications, it would be “difficult to disentangle” them because they had happened simultaneously.

Data extracted from Scopus by THE indicate that the share of research from mainland China that featured any international collaboration appears to be plateauing as well.

After climbing from about 14 per cent in 2010 to 23 per cent in 2018, it stalled at this level in 2019 and 2020, with current data for 2021 showing a drop back to 22 per cent.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, said care had to be taken with these data because rapidly growing science systems might also be increasing their domestic output at a similar or higher rate.

“If both international collaborations and national collaborations are increasing rapidly, and at the same rate, the apparent internationalisation curve flattens despite the big increase in cross-border connectedness,” he said.

He added that data up to 2020, the most recent complete year in the US National Science Foundation’s own indicators based on Scopus, were also still likely to “largely embody the working-through of previous trends in less divided times”.

However, Professor Marginson did say that the “strongest and most immediate effect of hostile geopolitics – one would expect – would be in the US-China co-authorship data”, although he added that a complete picture might not emerge until full NSF data for 2021 and 2022 were available.

后记

Print headline: US‑China research shrinks