The tenures of UK university leaders are growing longer, reaching more than eight years on average, “despite the enormous pressures and (sometimes) personal abuse faced by those who fill this important role”, the Higher Education Policy Institute has found.

A policy note by Hepi director Nick Hillman, published on 26 May, with executive search firm GatenbySanderson, looks at various ways of measuring tenure. The average tenure of departing vice-chancellors on a 10-year rolling average “shows that, possibly against expectations, the tenure of serving vice-chancellors has been rising and that, on average, vice-chancellors have served for a little over eight years when they stand down”.

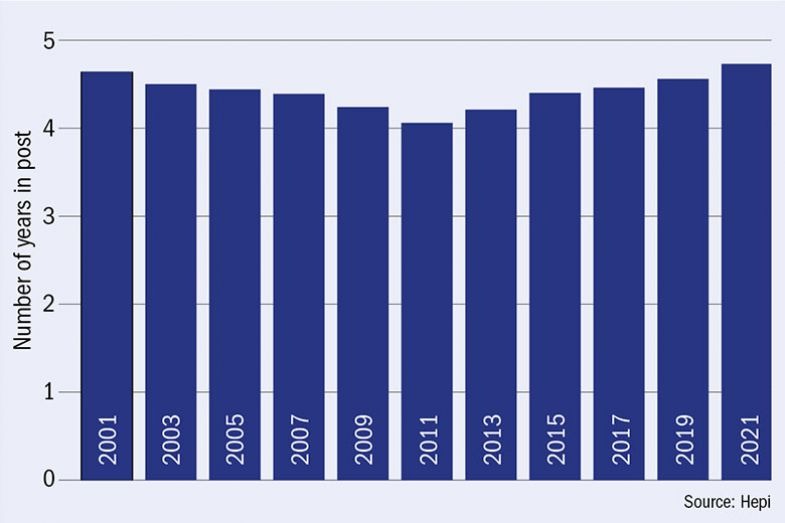

Average tenure of serving vice-chancellors in years (10-year rolling average)

For serving vice-chancellors, the average “is now approaching five years”, up 15 per cent from its lowest point about a decade beforehand. “Back in 2010, just one vice-chancellor (2 per cent of our sample) had a current tenure of 10 or more years; in 2021, eight did (16 per cent),” says the paper.

“While we do not regard the data presented here as definitive, it is notable that – against expectations – vice-chancellors’ tenures appear to be increasing rather than falling, despite the enormous pressures and (sometimes) personal abuse faced by those who fill this important role,” writes Mr Hillman.

This, he adds, “may indicate at the very least that university governing bodies have no less faith in today’s generation of university leaders than in the fairly recent past, despite the extra demands of the job. Perhaps vice-chancellors are getting more things right than wrong.”

But “it seems unlikely that tenure will go back up to the levels of the distant past, when the vice-chancellor role was arguably less demanding and a small number of individuals stayed in post for decades”, he continues.

Mr Hillman also notes that “while around 57 per cent of students at UK universities are female, only around 30 per cent of institutions are currently led by women”.

In light of factors such as increasing market competition in England and pandemic-driven uncertainty, he concludes: “One possible explanation for the average increasing tenure of serving vice-chancellors is that, in challenging times, changes at the top may seem to governing bodies like an unnecessary risk. Moreover, many vice-chancellors may well have felt an obligation not to walk away from their institution in turbulent times.

“Even assuming such conjectures are correct, however, it is not inevitable that tenure will continue growing as the sector stares into the face of growing funding pressures, continuing industrial relations problems and fallout from the so-called ‘culture war’.”

Mr Hillman told Times Higher Education: “It used to be said that ministers spend their first year making mistakes, their second year correcting their mistakes and that they only start doing their jobs well in year three.

“That might ring true to some vice-chancellors, given the size of the typical university. Eight years feels about right because it gives a leader the time get to know their institution before compiling a strategy and then seeing most of it through.”