Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine is reshaping international research collaboration, according to data that confirm that Russian scholars are partnering less with the West and gravitating towards China.

The analysis – by the technology company Digital Science, based on its Dimensions database – is the first to confirm that Western boycotts of Russian academia, imposed swiftly after February’s invasion, are having a significant impact.

“There’s clearly been a change in the collaborative landscape,” said Daniel Hook, the chief executive of Digital Science, who analysed the data.

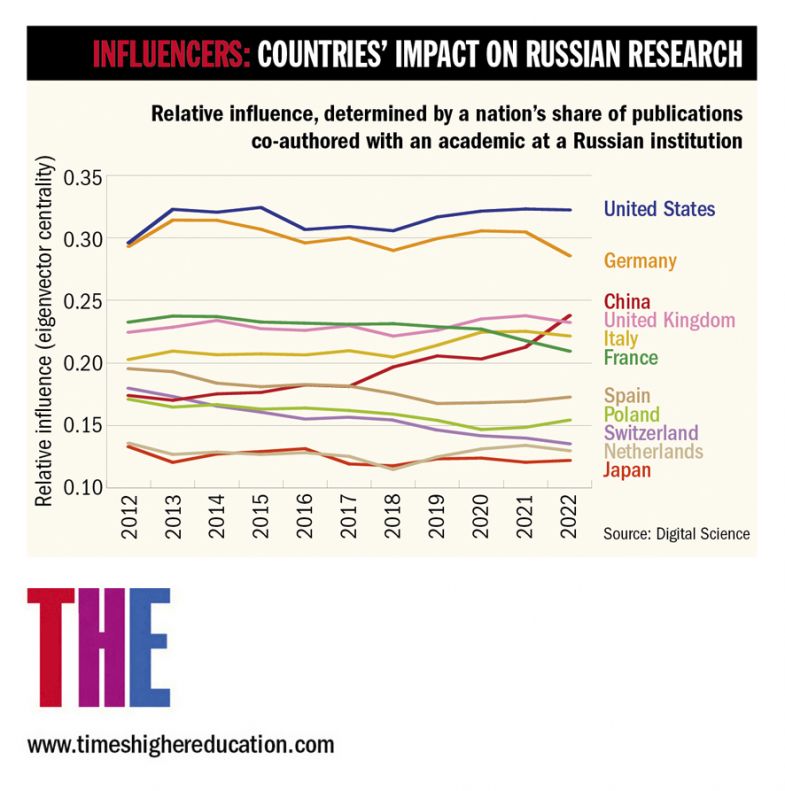

In a graph, Dr Hook shows the relative influence of different countries on research in Russia, which is determined by a nation’s share of publications co-authored with an academic at a Russian institution. The approach, which is more complex than a simple number of co-authored publications, gives a nuanced view of how research sectors interact.

“This metric has this zero-sum element. If the UK’s influence on Russia goes down, someone else must go up – that could be Russia’s influence on itself [co-authored internal publications], or it could be China,” he noted.

Already there appear to be “inflection points”, which mark a shift in the trajectory of research influence, for most countries in the current year, he said.

In the past 11 months, there has been a downturn in most Western nations’ influence on Russia, whose activity with its largest collaborators by far, the US and Germany (about 5 per cent of Russia’s output is written with a collaborator in either country), has taken a dip.

According to Dr Hook, it is “definitely a possibility” that China could become Russia’s key research partner before long. Extrapolating from the current trends, he suspected that it would “probably” pass Germany next year and “potentially” overtake the US in 2023 or the following year.

He predicted that the effects of the war on Russia’s collaborations would be more pronounced in 2023, when publications – which typically take three to six months to review – reflect the full brunt of geopolitical policy. “We will see the full effects of this next year,” he said.

Already this year, China has passed Russia’s third, fourth and fifth most influential research partners: the UK, Italy and France.

Among few countries to buck the trend, Spain and Poland saw a small uptick in research influence on Russia. This, Dr Hook speculated, reflected Spain’s relative distance from the conflict and, potentially, Poland’s “inability to walk away” from longstanding research ties with Russia.

At the same time, there has been a sharp rise in China’s line on the graph. The steep incline shows that China’s relationship with Russia has remained level even as other nations have retreated from collaborations, said Dr Hook.

“Everyone else is backing away from Russia, and China is just keeping constant – China’s growth rate in research is so high that even by keeping constant, their influence over Russia grows,” he said.

Many funders and universities cut support for collaboration with Russian universities in the wake of the invasion, with individual academics also choosing to end partnerships.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, noted that the rise of China’s links to Russia came amid significant geopolitical turbulence.

“This coincides with the US ‘China initiative’ and the noise about technological competition and security risks, which has reduced China-US collaboration. The geopolitics might have driven some transfer of Chinese international activity from the US to Russia,” he speculated.

Still, he predicted that China-Russia collaborations would eventually hit a wall.

“If that is what is happening, there are clear limits to it. Even aside from the disruption triggered by the war in Ukraine, Russian science does not have the capacity to engage cutting-edge collaboration from China on anything like the scale of the US science system or even several science systems in western Europe,” he said.

Professor Marginson said that while the Chinese government appeared to be distancing itself from Kremlin policy on the war, how this played out on scientific collaboration “remains to be seen”.

“Even if the isolation of Russian higher education and science stopped tomorrow, the damage to national capacity has already been very significant,” he said.

后记

Print headline: War reshapes international research ties