Source: Alamy

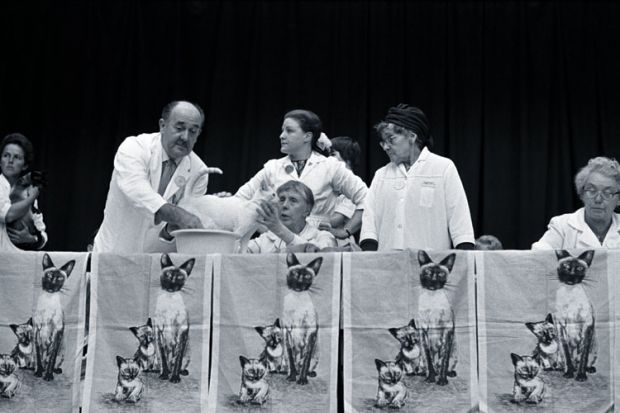

Among the pigeons: research found that ‘higher management scores are associated with better performance’

Departments in older, research-intensive universities are better managed, according to a new study that challenges “the commonly held view” that academics are “impervious to good (or bad) management”.

There is “a growing body of research that has demonstrated that good management practices improve firm performance” across all business sectors, say University of Bristol academics John McCormack, Carol Propper and Sarah Smith, in the paper “Herding Cats? Management and University Performance”.

But does this also apply within universities or is there something that distinguishes academics from “workers in most other organisations in ways that may make management tools less effective”?

In order to assess this claim, the authors measured “core operations-oriented management practices (monitoring of performance, setting targets and use of incentives)” in individual university departments. They then tracked these against “externally assessed measures of performance in both research and teaching”, namely rankings on the Complete University Guide website and performance in the 2008 research assessment exercise and the National Student Survey.

What emerged was that standard management techniques work even in academia: “higher management scores are associated with better performance on externally validated measures of both research and teaching”. With regard to specific tools, “good practice with respect to incentives – the freedom to retain, attract and reward good performers – is the most important correlate of good performance”. Far less significant were target-setting and monitoring policies such as performance tracking and review, despite having proved their worth in other sectors.

The authors also consider variation between types of university. Even after controlling for resources they point to “significant differences” in student satisfaction as well as research performance. Russell Group universities “typically score highest on measures of performance, followed by the other old universities, the former polytechnics and the other new universities”.

Part of the explanation, they suggest, is that “departments in older and more research-intensive universities tend to be better managed than departments in newer and more teaching-focused universities”. They note that “universities that decentralise incentives to the department level score more highly and this decentralisation is more common in the elite universities”.

Asked to comment on the paper, management expert Adrian Furnham, professor of psychology at University College London, said that there were “several features that make university management different and universities strange places to work in”, where academics “receive conflicting messages about being entrepreneurial, self-sufficient, etc, when they find their efforts are in reality highly controlled”.

He said that the reporting structure in universities was “unmanageable and unclear. Most dons have never been asked the simple question: ‘To whom do you report?’ They haven’t the slightest idea.”

Professor Furnham added that even if academics know to whom they report, there may still be about 50 people in a big department reporting to one person.

“The simple span-of-control idea, a Weberian concept, goes out of the window. Nobody can manage 50 direct reports, particularly if they are maverick dons,” he said.

“Herding Cats? Management and University Performance” has just been published online in The Economic Journal.