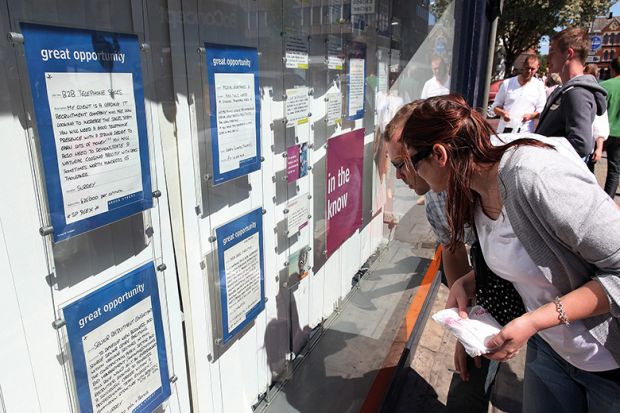

Undergraduates working part-time alongside their studies is becoming “the norm” during the cost-of-living crisis, forcing universities to reassess their teaching practices and judge how much of a role they wish to play in securing their students decent employment.

In the UK, polling earlier this year from the charity the Sutton Trust found that 27 per cent of students it surveyed had been forced to take on jobs or work longer hours as loans became stretched and other forms of income – such as parental support – dried up. A Ucas survey in April estimated that the number of students working part-time was 43 per cent.

Graeme Atherton, director of the National Education Opportunities Network at the University of West London, said students working had become the “norm” in some institutions, meaning “ostensibly full-time students are actually part-time because they are working half the time”.

In Australia, the numbers are higher. Andrew Norton, professor in the practice of higher education policy at the Australian National University, said the number of full-time students working had increased from about 40 per cent in the late 1980s to around 70 per cent in the last year. Typical hours worked had also been going up, he added, with half of employed domestic students working 20 or more hours a week, and a quarter working 30.

Universities are facing calls from students to condense timetables as a result – so they can have full days away from campuses to work – and make it easier to study at a time that suits them via recorded lectures and flexible deadlines.

Professor Norton said students who work have better employment outcomes and, while recent research was lacking, older studies had shown those working at “moderate levels” might also get higher marks.

Despite such positives, he said, many students appeared to be working to an extent that put them “in the potential academic danger zone of leaving too little time to study”. He said he was also concerned about the impact on the overall student experience, with poorly attended classes and lower rates of co-working possible consequences.

Dr Atherton said this had caused a “tension” that had led to an unwillingness among universities to face up to the extent of the issue, with a reluctance to monitor the types of jobs students do, and the conditions they face.

A key step, he said, was facilitating discussions with major part-time employers in the area to work out ways to ensure there was a minimum negative impact on study.

Neil Mosley, a consultant and expert in online and flexible learning, said the “new reality” required universities to go further in thinking about “how programmes are designed to support student success”.

“While recording of live teaching sessions and enabling students to join live teaching sessions remotely have offered students greater flexibility, they’re largely tweaks to the existing model of university learning and teaching,” he added.

A reduction in place-based timetabled teaching – with “greater emphasis on asynchronous teaching and learning” – would require much more radical organisational change, Mr Mosley said.

More thought needed to be given to ensuring learners still interact with one another and equipping them with the skills needed to successfully self-study, he added, and staff would require support and training to teach in this way.

Harriet Dunbar-Morris, dean of learning and teaching at the University of Portsmouth, said the institution had been reviewing key student engagement and attendance monitoring processes in light of the increased number of students with other commitments, including work and caring duties.

“It is key that students understand what we need them to engage in and why, and therefore how to organise their time and their other commitments and to what end,” she said.

Currently a blended approach combining online and in-person learning offers some flexibility, she added. “We are seeking to move to a situation that will allow us to schedule sessions in a more blocked way for students, allowing them to engage with their other commitments and with learning on certain days. This is not always feasible or desirable, but our blended and connected approach does allow for self-paced and independent learning.”

Portsmouth was also looking to create paid opportunities for its own students, offering a potentially easier way of coordinating their timetables and improving working conditions. The University of Essex too is spending £100,000 on creating 30 such roles between January and June.

The existence of such opportunities at a university and in the wider area could become a key factor for students in deciding where they wanted to study in the first place, according to Dr Atherton.

“Rather than a scenario where students are choosing a course and place of study and fitting part-time work around that, it is increasingly the other way around,” he said.