At the age of 81, Lord Baker of Dorking could be excused for taking things easy. But nothing seems further from his mind.

Although he was secretary of state for education and science way back in the 1980s, he has retained a deep interest in the subject, still chairs the Baker Dearing Educational Trust and, only three years ago, assembled a team to publish 14-18: A New Vision for Secondary Education.

Much of his efforts are devoted to creating a network of about 40 schools known as university technical colleges for students aged between 14 and 19. Since each is sponsored by a university, this gives him “regular contact with vice-chancellors, probably more than when I was a minister”.

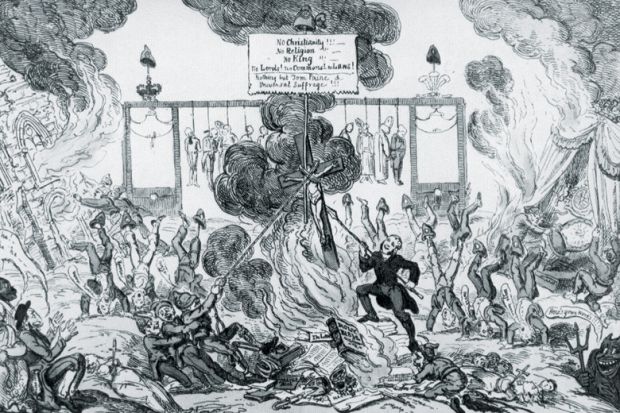

But his latest endeavour is a beautifully illustrated volume called On the Burning of Books: How Flames Fail to Destroy the Written Word (Unicorn).

He has been interested in the topic since he read John Milton’s Areopagitica, which he describes as “the greatest defence of free speech and liberty of expression in the English language”, at school. He has now spent several years assembling some striking examples of books going up in flames, whether through government decree, religious persecution or domestic accident.

University libraries, he points out, have often been in the firing line.

Serbian forces in 1992 deliberately targeted the records of the University of Sarajevo “because it contained too many records of Muslim ownership and Muslim establishments” in Bosnia. Universities in the Belgian city of Leuven were even more unlucky. Books were looted from one by Napoleon in 1795 and again from the Catholic University of Louvain by the Kaiser in 1914, although this was just a prelude to the artillery barrage that destroyed a million volumes in 1940.

So how does he feel about what some see as a censorious climate within today’s universities?

Since “universities are essentially about exchanging ideas”, he says, he disapproves of excluding any groups, “whether they are fascist or communist or sexist or whatever…When I went to open a new science lab at one university, the Socialist Workers Party turned up from the local town and I was kicked to the ground and broke my glasses. But even so I didn’t want the Socialist Workers Party banned from universities.”

Lord Baker introduced “per-capita funding for universities” and “the first student loan scheme” as deliberate steps on “the pathway to fees”, although “I don’t think I could have got fees through even the Thatcher government in 1988”.

Nonetheless, he believes that current tuition fees are too high and suspects that, if the “absurd” decision to remove universities from the Department for Education and Skills hadn’t been taken in 2007, it would have been possible to find extra funds within the much larger budget.

He is therefore “delighted” that the new prime minister has moved universities, and skills, back into that department’s fold. “They should never have left, for education is a continuous process from the ages of four to 18 and then through further and higher education and beyond.”

Although reluctant to comment about his ministerial successors, Lord Baker does take issue with the way that secondary education under Michael Gove became “too focused on academic subjects”. This, in his view, is “a totally wrong policy – the idea that those at the bottom of the heap, the white poor boys, will get up the ladder by reading Pride and Prejudice”.

The first British minister for information technology, he waxes lyrical about the prospect of introducing 3D printers into primary schools. Yet he recently published a sobering booklet on The Digital Revolution, predicting, he says, that “we are heading into an area of rising unemployment…We are seeing a hollowing out of middle management, which will impact on all those people who left university with humanities degrees and expected to join a big company and be there most of their lives.”

All this poses some major problems for universities.

Lord Baker foresees that “more students will start thinking: ‘What are the job opportunities from doing that particular course?’ – which might encourage more people not to go to university”.

Vice-chancellors will need to embrace “much more practical courses, designed very much where the jobs are going to be” and less costly part-time courses allowing students to “learn and earn”.

They will also have to be more inventive in attracting overseas students, assuming that future ministers share Lord Baker's preference for “being fairly liberal with visas for students as long as they come to proper institutions”.

Fortunately, he is impressed by the way that many of today’s vice-chancellors have become “quite entrepreneurial” and skilled at adapting to change.

Things were rather different in his youth. During most of Lord Baker’s time as a University of Oxford undergraduate in the 1950s, he recalls, the vice-chancellor was a man called Alic Halford Smith. His best-known publication was a lecture titled “Idleness as a part of education”.

后记

Print headline: ‘Exchange of ideas’ on campus essential