As universities around the world step up their efforts to combat essay mills, knowing which students are more likely to pay someone else to complete an assignment for them is increasingly important.

A recent study found that as many as one in seven recent graduates may have been guilty of contract cheating and, for Western university sectors that are increasingly reliant on international students, emerging evidence points towards an uncomfortable truth that such learners may be more likely to break the rules than their domestic peers.

Some essay mills are targeted specifically at international students. The issue was thrust into the spotlight in 2013 when a contract cheating service aimed at Chinese-speaking students in New Zealand, called Assignments4U, was exposed. The following year, hundreds of students at 16 Australian universities were found to have used the contract cheating site MyMaster to write their essays and even to sit online exams for them. Written in Chinese, the website was aimed at Chinese studying abroad.

Looking at cheating and plagiarism as a whole, a 2016 investigation by The Times into more than 100 UK universities found that students from outside the European Union were more than four times as likely to be caught cheating as their classmates from inside the bloc, including the UK. The same year, a Wall Street Journal analysis of data from 14 leading US colleges found that international students were five times more likely to be found guilty of cheating than their American counterparts.

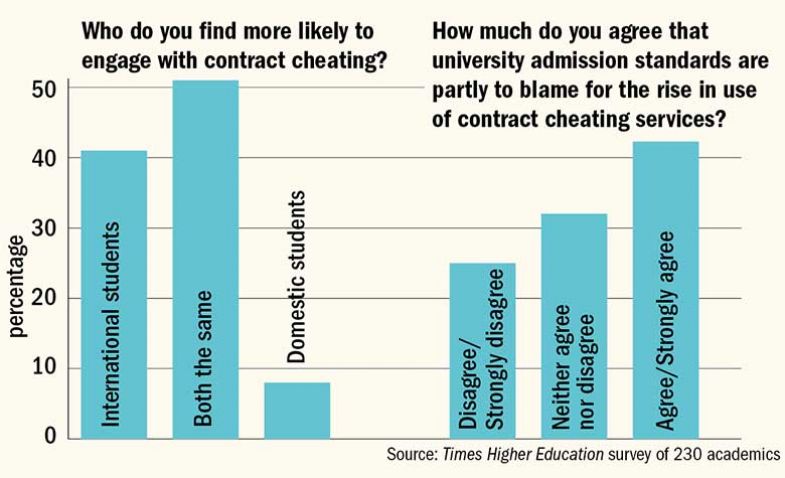

A self-selecting survey of 230 academics from around the world conducted by Times Higher Education adds fresh evidence to the debate. Asked whether international or domestic students were more likely to use contract cheating services, 51 per cent said that the risk was the same for each group; but 42 per cent said that international students were more likely to use essay mills, compared with only 8 per cent who identified domestic learners as being the greatest danger.

As the THE survey indicates, none of this is to say that domestic students’ use of essay mills is not a significant problem. However, many academics regard the challenges facing international students as the elephant in the room of the contract cheating debate, and one that can no longer be ignored.

Anecdotally, sector experts identify a range of issues that might make some international students more likely to cheat: for some, having English as a second language; in a number of cases, the intense pressure to succeed that comes with having a significant proportion of familial income invested in your education; and perhaps an unfamiliarity with Western academic norms and experience of a more didactic educational culture in which reciting others’ words is seen as a mark of respect, not plagiarism.

Emerging academic evidence supports some of these assumptions. A 2018 survey of about 14,000 students in eight Australian universities found that students who spoke a language other than English at home were significantly more likely to say that they had cheated in assessments than those who used English. A 2015 UK study that explored which students were most likely to purchase essays came to similar conclusions.

Tracey Bretag, director of academic integrity at the University of South Australia Business School and one of the authors of the Australian study, told THE that it was important to note that the findings were about language, not national or cultural heritage. “Our research found that domestic students for whom English is a second language also had serious problems. Of course the bottom line is, at least in the Australian context, 80 per cent of our second language learners are international,” she said.

For Dr Bretag, the problem is that in the drive to recruit more international students – and the hefty tuition fees they command – the language requirements needed to study at university have become too low.

The most common official assessment of English language ability used by Western universities is the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), which grades students from one to nine. Universities usually require a minimum score of six, while in the UK the government minimum is 5.5, but native English speakers would score a nine. “[A six] is not adequate for the linguistic manipulation you need for academic writing,” Dr Bretag said.

Who’ll pay to stay the course? Perceptions of cheating

In a 2018 paper, Danijela Trenkic, an associate professor in second language education at the University of York, found that the English vocabulary of international students in the UK was on average just under half the size of that of home students, even though the students in the study all had an IELTS score of 6.5 to 7.5. Furthermore, they read and processed information in English at half the speed, understood significantly less of what they read and were less able to summarise in writing what they had read.

According to Dr Bretag, although these students arrive at university thinking they are prepared for the rigours of academic study, they are not. “We set them up for failure, knowing that they will need more support and a lot more training…and they don’t have time to access any non-mandatory support that is on offer,” she said. “Then, on top of that, we have unscrupulous, marketing-savvy essay mills that target those vulnerable students.”

Rather than disappoint their parents – who have often worked hard to afford to get them there – the students turn to contract cheating, she said.

Lord Storey, the Liberal Democrat spokesperson for education in the UK’s House of Lords, agreed that many of the students who resort to essay mills do so for this reason. Lord Storey put the main problem international students have down to “cultural learning differences, because education is different between countries. How students learn in Asia is different to how you learn in the UK, and that is different to America, for example.”

A 2018 paper by Louise Kaktiņš, a lecturer in the linguistics department at Macquarie University in Sydney, which found “particular concerns” regarding international students and contract cheating, said that their use of essay mills was a side-effect of the “increasingly corporatised, commercialised university culture”.

“Universities are now in fierce competition with one another for a share of the international student market,” Dr Kaktiņš told THE. “It is not surprising that entry requirements for international students are becoming less stringent and increasingly flimsy and porous, especially as regards students’ academic suitability.”

In THE’s survey, asked whether university admission standards were partly to blame for the rise in contract cheating, 43 per cent of respondents agreed that they were. Only a quarter (26 per cent) felt that they were not, while a third (32 per cent) were undecided.

One Australian respondent said that international students were more likely to turn to essay mills “because we assure them that their English is of a sufficient standard to get by in our courses when often it isn’t – that is our fault, not theirs. The purchasing power of international students has been used in lieu of appropriate and sustainable government funding. We should hardly be surprised if that purchasing power is used in ways we can’t control.”

However, Cath Ellis, associate dean (education) in UNSW Sydney’s School of the Arts & Media, cautioned that the perception that international students were more likely to contract-cheat might actually be because academic staff found it easier to detect in the work of students for whom English is a second language. “These students are probably less able to cover their tracks. In other words, it may actually be a kind of reporting bias,” she said.

How, then, should universities respond? Singling out international students might serve only to increase their isolation and push them towards essay mills, and the perils of this approach were demonstrated earlier this year when the University of Liverpool was forced to apologise for sending an email suggesting that international students did not know what cheating was.

Many of the solutions apply to all students: the Republic of Ireland recently said that it would follow New Zealand’s lead and make essay mills illegal, while technology company Turnitin last week launched Authorship Investigation, software that claims to be able to use machine-learning algorithms and forensic linguistic analysis to detect whether a student is indeed the author of a submitted essay.

Some academics recommend a shift to more assessment by exams, rather than essays, while others advocate greater use of vivas and other forms of assessment that involve direct interaction with academics.

For South Australia’s Dr Bretag, the most significant step relating to international students would be to introduce higher language-related entry requirements. “But there need to be strict criteria on the agents who recruit international students and to make sure our IELTS testing centres, and other centres, are free from corruption,” she said. “I’ve spoken to students who can barely speak English and yet they show me their certificate and it says 6.5.”

Dr Kaktiņš recommended the introduction of invigilated “diagnosis” exams when international students arrive to stream them into the right preparatory courses, while Dr Ellis said that institutions needed to provide better support to students who found themselves struggling with language and academic culture.

However, both Dr Bretag and Dr Kaktiņš said that success would be limited without more government funding for universities that are reliant on international student fees.

“[Contract cheating by international students] is a symptom of a wider issue in higher education. It’s a system under stress,” Dr Bretag said. “It’s not good enough to blame institutions for being inefficient with funding, to blame tutors for not doing a good enough job in teaching or catching cheating, and it’s certainly not good enough to blame students, particularly second-language learners, for being cheaters.

“It’s a systemic issue and, unless we look at the big picture, all we’re doing is putting band-aids on minor players who can do very little to change things.”

后记

Print headline: Impossible ascents, devious devices and difficult questions