By common consensus, the global financial crisis of 2008 was extremely damaging for public higher education in many countries. Its legacy in several nations was either many years of austerity that forced universities with a significant dependence on taxpayer funding to make cutbacks, or the ushering in of greater reliance on private money such as tuition fees to keep budgets afloat.

But as we finally move away from the 2010s – in which so much was seen in the context of post-crash public finances – is the public funding of universities on the way to recovery? Are there systems that have been permanently altered? And did any country largely escape the squeeze?

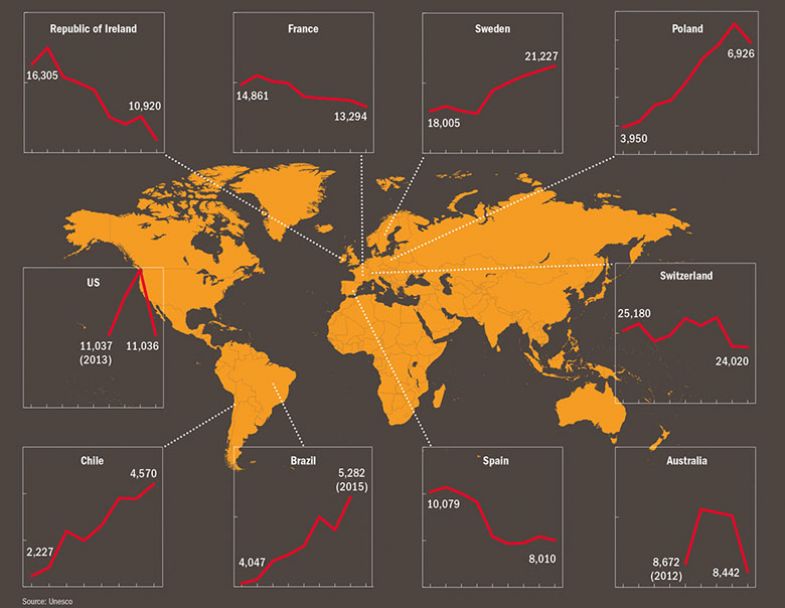

Data from global organisations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation can help to illustrate how different countries reacted to the crisis in terms of spending on universities.

A measure of initial government expenditure on tertiary education per student, adjusted for inflation and the varying cost of living in different countries, suggests that among the nations that fared the worst were the Republic of Ireland, where public investment in the student unit of resource fell by a third from 2008 to 2016, and Spain, where it dropped by 21 per cent. Other European countries such as France (down 11 per cent) also took a substantial hit, while some kept public spending relatively high but with variations year by year, such as Switzerland.

Some developing university systems have raised their funding significantly despite the crisis, although from such a low base that they are still behind many countries: Chile (up 105 per cent), Poland (up 75 per cent) and Brazil (up 31 per cent to 2015) are examples here.

But one nation that incredibly appeared to keep growing investment during the period, despite already being among the most developed systems, was Sweden. By 2016 it had increased its government expenditure per student by 18 per cent compared with 2008, with the public unit of resource standing at more than $21,000 (£16,000).

Marita Hilliges, secretary general of the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions, said the fact that most research funding in Sweden was funnelled through universities rather than institutes explained much of this per student growth. The financial crisis also hit Sweden earlier than many other nations.

But she said that there had also been a political choice to keep funding stable in the sector, with higher education being seen as a key way to deal with unemployment, by providing training for young people.

“There have been no major budget cuts in modern times in our sector. We have been used as a labour market regulator…so [higher education] has been a political instrument for difficult employment situations,” she said.

However, she said one concern in the country had been that a lot of money needed to be spent by universities to win research funding because of the extremely competitive regime.

“Like in all very competitive systems, it takes a lot of resources just to compete. It is [an issue that is] heavily discussed in Sweden because, [compared with] other OECD countries, we have high levels of competitive funds,” said Professor Hilliges.

“The government and all the political parties have said that they would like to change this…because they don’t find it optimal, but so far there has been no real action.”

Thomas Estermann, director for governance, funding and public policy development at the European University Association, which is soon to release its latest Public Funding Observatory data on European higher education, said that the situation in Sweden showed that when you “zoom in” on the figures even the better-off nations face challenges.

“If [competitive funding] it is too high, then you spend an enormous amount of resources on that. There is a question of the efficiency and effectiveness of the system,” he said.

Countries that have switched more to a system of student contributions to replace lost public money – such as England – could also face other efficiency costs.

“[If] you shift more towards funding through private contributions from students – even if supported by loans – it is clear that this raises the pressure [among institutions to] provide an equivalent value [to each other] and that is not always about the quality of the education,” Mr Estermann said.

It is also a discussion that has often been at the forefront of the debate in the US.

Unesco figures do not show the relative public per student spend from 2008 to 2016, but the latest data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association suggest that state government funding for public institutions was still down 11 per cent since the recession, albeit with considerable variation between areas.

Again, tuition fees have picked up the slack here, and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development figures show how, when including public and private funding, the picture over time can be more consistent.

Andreas Schleicher, head of the OECD’s education and skills directorate, said that in “most cases” reductions in public funding among members have been “offset by an equivalent increase in the share of private funding”.

“This is the case, for example, in Spain, Ireland and Italy, where the share of public funds decreased by about 10 percentage points in 2016 compared with 2005 but the share of private funds increased by the same amount,” he said. Others, such as Chile, have seen a shift the other way.

OECD data also show how fluctuations in student numbers can affect the figures: Australia has dropped back on per student spending because funding has not always kept pace with growing intakes.

On the rebound: government spending per student on tertiary education, 2008-2016 (PPP$, 2016 prices)

But, however funding is measured or directed, are there systems that may have been permanently damaged by the crisis?

Mr Estermann said one important factor to consider here was the long-term effect of several years of underfunding, especially in terms of the strain it may have placed on infrastructure.

“There has now been almost a decade of massively reduced funding, and that means that you will have a backlog, certainly in…infrastructure investment,” he said, something that cannot be rectified overnight. In this respect, Mr Estermann said, “I think the funding situation will never be like it was in 2008.”

Such considerations become even more significant when factoring in the fact that universities will be expected – and often regulated – to cut their carbon emissions.

“That, I think, for many systems is a big challenge in the future. You can see that in the next decade there will be a much stronger pressure to adapt your infrastructure to the…green agenda,” Mr Estermann said, pointing to the impact of programmes such as the European Commission’s recently announced Green Deal.

Because of this and recent underfunding, “in the future there will probably be a strong need to address the infrastructure investment, and that could be a huge challenge for many institutions”, Mr Estermann added.

simon.baker@timeshighereducation.com

Listen to Simon Baker discuss this story in a data special podcast

Download this podcast

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: Has international HE recovered from the financial crash?