English universities spent more than £112 million on severance payouts last year, with thousands of staff members departing their roles – but most institutions continued to grow, adding almost 11,000 positions in total.

Analysis by Times Higher Education of the accounts of 73 institutions that have so far published information on redundancy, severance pay and other forms of compensation showed the total bill in 2022-23 was £44 million more than the £68 million spent by the same institutions the year before.

While 5,786 staff were affected in 2021-22, this figure had risen by 1,036 last year to 6,822 – meaning each person received, on average, a payout of £16,000.

The data come at a time of upheaval in the sector, with more restructures planned by several institutions as they reorganise course offerings in response to a difficult financial climate.

Experts said the situation was also reflective of the high number of fixed-term roles in higher education, with many qualifying for compensation if they exit a post after serving for more than two years.

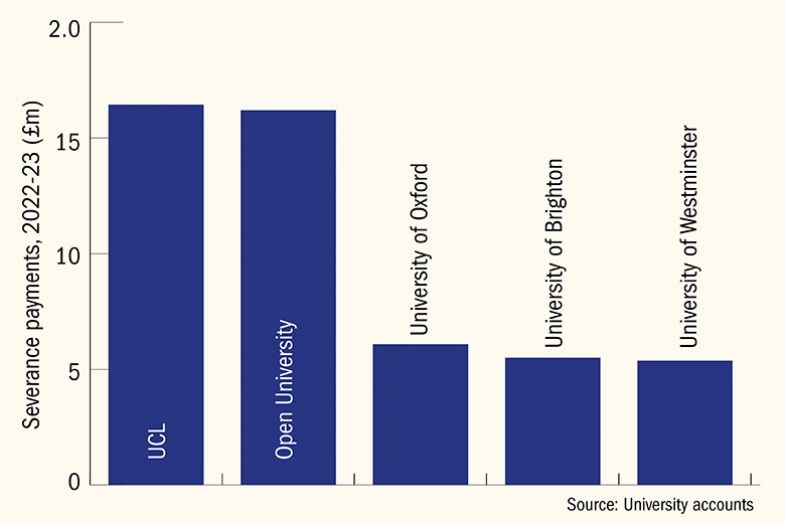

Institutions that have struggled financially were among those that ended the year having spent millions on paying off staff. The University of Brighton’s bill was £5.5 million, with 165 jobs lost in 2022-23, up from £300,000 for 36 the year before. Birkbeck, University of London and the University of Wolverhampton spent £3.8 million and £2.7 million respectively.

UCL and the Open University – two of the country’s biggest institutions – spent the most, with £16 million each on payouts.

The OU said this included a provision of £14.9 million “for future restructuring commitments through voluntary severance schemes” and had not all been spent in the past year. A spokesperson said it had been open about “our need to achieve a correction in our annual operating budget over a four-year period by reducing costs and bringing in new net income”, and it remained committed to “exploring all possible measures in an effort to avoid compulsory redundancies”.

UCL said it had also run a voluntary resignation scheme that accounted for the high number of departures. Despite this, the institution saw a net increase of 1,000 full-time-equivalent roles last year, its accounts show, jumping from 16,215 to 17,291.

Top five: Golden goodbyes

Overall, just 10 of the 73 institutions ended the year with smaller staff teams than they started with. With a net loss of 204 full-time-equivalent roles, Wolverhampton shed the most jobs, followed by 60 at both Birkbeck and St George’s, University of London, which said the shrinkage reflected the dissolution of its joint faculty with Kingston University, and not a redundancy programme.

A total of 39 universities added more than 100 full-time positions, with many growing their academic and research capacity as well as their professional services functions.

Phil McNaull, a former finance director at Heriot-Watt University who now works as a consultant, said that although redundancy and severance payments were “built in” to universities’ way of operating – particularly in research, which is dependent on short-term grant funding – the situation was reflective of how several institutions had been forced to look “long and hard” at their operating business models and cut areas seen as less lucrative while investing in activities that they hoped would bring in more income.

As staff costs represent the biggest outlay for most institutions, making redundancies would always be seen as a short-term solution for those facing a cash crisis, he added.