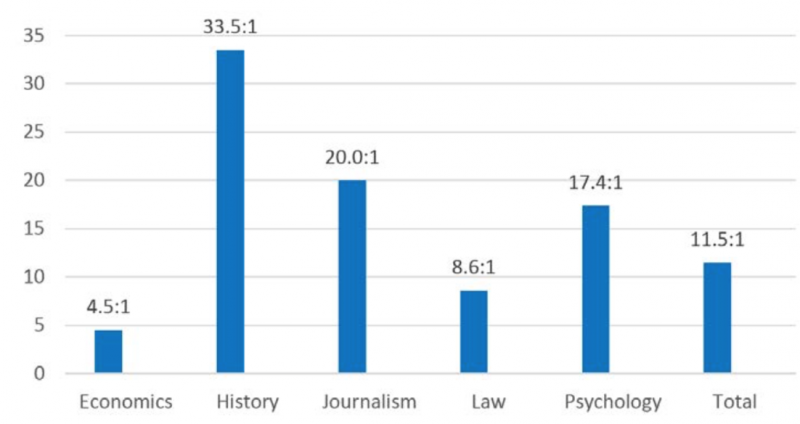

In any US election cycle, there are bound to be references – some of them disdainful – to “liberal academia”. A new study is sure to elicit a least a few more such references, finding that social scientists who are registered to vote skew overwhelmingly as Democrats – 11.5 for every one Republican at top universities, to be exact.

The study, published online by Econ Journal Watch, considered voter registration data for faculty members at 40 leading US institutions in economics, history, communications, law and psychology. Of 7,243 professors in total, about half are registered. Some 3,623 are Democrats while just 314 are Republicans.

Economists are the most mixed group, with a ratio of 4.5 Democrats for every Republican. Historians as a group are the most lopsided, at 33.5 to one; the paper attributes this to the rise of specialisations such as gender, culture, race and the environment. (Some classify history as one of the humanities disciplines.) Lawyers are 8.6 to one and psychologists are 17.4 to one, while communications scholars, including journalism professors, are 20 to one.

The ratios have become more extreme since 2004, according to the study, and age profiles suggest that trend will continue. That is despite researchers’ concerns that current data may be “somewhat abberational”, given the polarising candidacy of Republican Donald Trump for president.

Ratios are higher at more prestigious universities and lower among older professors and among those with higher ranks, according to the paper. There are also regional effects, with ratios highest in New England. (This finding replicates one recently made by a Sarah Lawrence College professor.) Women are much more likely to be registered Democrats, at 24.8 to one. Among men, the ratio is nine to one.

“People interested in ideological diversity or concerned about the errors of leftist outlooks – including students, parents, donors and taxpayers – might find our results deeply troubling,” the authors say.

Data were only readily available to the researchers for 30 states, based on voter privacy policies and the database used, Aristotle. So their study included information on professors at 40 of the 60 top US universities.

Comparisons are somewhat imperfect, as some institutions don’t have all departments studied. Some departments don’t have any Republicans, but also have relatively few professors over all. Nevertheless, Brown University has the highest ratio for all five disciplines combined, at 60 to one, Democrat to Republican. It’s followed by Boston University (40 to one), Johns Hopkins University and the University of Rochester (both 35 to one), and Northeastern University (33 to one).

The lowest ratio – that is, the most even mix of registered Democrats and Republicans – is at Pepperdine University, at 1.2 registered Democrats for every Republican. Case Western Reserve University is next, at 3.1 to one. It’s followed by Ohio State University (3.2 to one) and Pennsylvania State University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (both six to one).

The authors acknowledge that being registered to vote by party isn’t the same as voting that way in every election. But they estimate, based on a number of assumptions, that active humanities and social sciences faculty will vote at a ratio of about 10 to one, Democrat to Republican. That’s up from a 2004 estimate of about eight to one.

“The reality is that in most humanities/social science fields a Republican is a rare bird,” the paper says. It notes that registrants to either the Green Party or Working Families Party equalled or exceeded Republican registrants in 72 of the 170 departments studied, including economics departments. So in 42 per cent of departments, “Republican registrants were as scarce as or scarcer than left minor-party registrants”, it emphasises.

Republicans exceeded Democrats in only four departments of 170 total: economics, history and law at Pepperdine and economics at Ohio State.

“Faculty Voter Registration in Economics, History, Journalism, Law and Psychology” was written by Mitchell Langbert, associate professor of business at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York; Anthony J. Quain, a health economics solutions developer; and Daniel Klein, professor of economics at George Washington University and editor of Econ Journal Watch. They describe themselves in the paper as a dying academic class of “classical liberals”, generally opposed to “governmentalization”.

They refer to both the Democratic and Republican parties as “horrible”, but say that, when pushed, they usually favour a Republican political candidate over a Democrat.

“Democrats are, often without being very self-aware about it, more deeply enmeshed in bents and mentalities that spell statism than are Republicans,” the paper says, “who show more diversity – think of all the species tagged ‘right’ – and allow greater place for the classical liberal tendency.”

So what?

All that leads to an essential question: beyond being interesting, do these findings matter? Do professors’ political views infiltrate their teaching and, even if they do, are students affected? Several other studies suggest that classroom attempts at indoctrination don’t work. Additional data suggest that students are increasingly liberal before they even arrive on campus. And some might note that, in recent years, Republican politicians at both the state and federal level have repeatedly questioned the value of the social sciences.

Langbert said via email that the data do matter, because organisational cultures “reflect the value assumptions of the members and leaders”. When a trait becomes uniform within an organisation, he said, “it generally reflects uniformity of thought…The absence of views alternative to the social democratic culture in universities implies uniformity of opinion. It is difficult to conceive how with such uniformity there can be a fair accounting of alternative views.”

Walter E. Block, Harold E. Wirth eminent scholar endowed chair in economics at Loyola University in New Orleans, applauded the study for, in his words, documenting “the bias of the professoriate toward socialism, communism, interventionism, liberalism, progressivism, political correctness, cultural Marxism, etc., and away from classical liberalism, conservatism, free enterprise and libertarianism”.

Block added that he thought professors have “an impact on the thinking of the next generation”, as evidenced by former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’ popularity on college campuses.

Neil Gross, Charles A. Dana professor of sociology at Colby College, has written about why professors tend to be social democrats (and Langbert has challenged some of his assertions). He said he couldn’t comment on the new study because he hadn’t read it in detail, but also said that no one “should find it surprising that there aren’t many registered Republicans in academia at this point”. The party “has long been losing support among the highly educated”, Gross added. “My impression is that the candidacy of [Trump] has greatly exacerbated those losses.”

This is a version of an article that first appeared on Inside Higher Ed