Australian academics are shunning the world’s emergent science superpower, with Chinese research partnerships vanishing from key Australian Research Council (ARC) grant schemes.

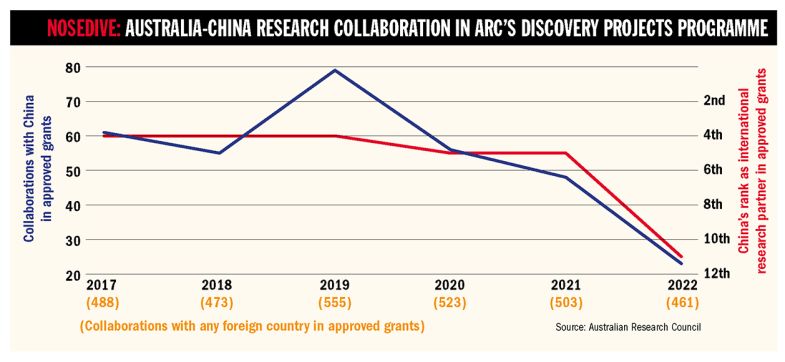

China is normally among the top five international partners in successful applications to Discovery Projects, the ARC’s biggest annual funding stream and its key support mechanism for basic research. There are about 50 to 80 collaborations with China in each year’s grants. That fell to 23 in the latest funding round, relegating China outside the top 10 contributing countries.

A similar slump occurred in the Linkage Projects scheme, which supports strategic alliances in applied research. China is usually among the top three collaborating partners but dropped outside the top eight in the latest funding round. It barely featured in this year’s Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities grants, dropping outside the top 10 collaborating countries.

Applications to the three funding rounds were submitted mostly in early 2021, amid rising tensions between the two countries. The ARC figures offer the first empirical support for anecdotal accounts that Australian researchers have started steering clear of China as a research subject or partner.

Until recently, China was on track to usurp the US as Australia’s top research partner after overtaking the UK several years ago. The number of journal articles co-authored by Chinese and Australian researchers grew by 84 per cent over the five years to 2021, compared with 25 per cent for US-Australian publications, according to the Scopus database of indexed research.

But that growth may have tailed off, according to an analysis by University of Arizona researcher John Haupt, who found that the annual double-digit increase in Chinese-Australian publications had slumped to just 4 per cent last year – although some 2021 publications were still to be tallied.

The ARC says that its processes are “country agnostic”, suggesting it does not weed out applications with China. Rather, fewer such applications are being submitted.

“Just the mention of the word ‘China’ is sending shivers down researchers’ spines,” said University of Sydney education professor Anthony Welch. He said Australian-based academics with Chinese heritage were especially careful to avoid attention. “They’re feeling like they need to put their heads down.”

China is the unannounced target of an Australian parliamentary inquiry and a number of regulatory crackdowns launched over the past 18 months. Updated foreign interference guidelines unveiled late last year oblige academics to divulge their overseas affiliations, while an act passed in late 2020 gives Australia’s foreign minister veto powers over agreements public universities strike with overseas governments and their entities.

Last year, four top universities reportedly engaged China expert John Garnaut, a former adviser to prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, to audit their staff for potential foreign interference risks. But vagueness about the government’s intentions have left universities and researchers second-guessing the rules. Last year vice-chancellors complained that they had never seen an expanded list of sensitive technological areas in which collaborative research with some nations was to be avoided.

Professor Welch said Australia risked throwing “the baby out with the bathwater”, as security concerns trumped all other considerations. He said Chinese medical scientists could prove productive research partners despite their connections to the People’s Liberation Army, which had “some of the better hospitals in China. They may be researching kidney disease. Do we catch that nuance? Probably not.”

He said Australia had much to lose from deteriorating research ties with China – especially in fields such as chemistry, engineering and maths, where China was Australia’s leading research partner and helped produce highly cited papers.

China is also among the biggest source countries of foreign-born academics, contributing as many as the UK. Dwindling research opportunities for the Chinese diaspora could cost Australian universities many staff.

Expert-endorsed grants for two China-related projects were among the six rejected late last year by acting education minister Stuart Robert. Jane Golley, a China specialist at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy, said the vetoes suggested research could struggle for funding unless it matched a predetermined narrative.

“Ten years ago, it was all about understanding China from multiple perspectives. Now it seems that our government has decided what China is and will only approve research that supports that story. There’s been a significant shift away from an interest in understanding China deeply,” she said.

Peter Jennings, executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said he suspected that some Australian academics were “self-censoring” over fears that collaborating with China could undermine their prospects of funding. But others considered cooperation with China “distasteful”.

“You’re effectively partnering up with a totalitarian system which is changing Chinese education. Xi Jinping’s civil-military fusion strategy is really designed to bring the university sector more closely into collaboration with the defence and intelligence world in China,” he said.

“I’m not saying that we shouldn’t have any research connections to China but we need to be very open-eyed as to what that entails. You can’t think of Chinese universities as independent entities.”

后记

Print headline: Collaboration between Australia and China slumps