Marian Mahat, a senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education, believes it is important for women to talk about their often unconventional and difficult routes into academia.

“My academic bio is me; but my personal story is the real me,” she told a forum hosted by the Consortium for Higher Education Research in Asia (CHERA) at the University of Hong Kong.

Dr Mahat said that she withdrew from her first attempt at a PhD in order to move because of her husband’s job. She then suffered a miscarriage, became a mother and began another job, only to have to move again for her husband. Finally, in the year her marriage fell apart, she started her second attempt at a PhD in 2013.

“I worked after the kids went to sleep. I worked on weekends. During one conference in [Washington] DC, I watched my daughter cry on video because she missed me,” she said.

Dr Mahat is the editor of Women Thriving in Academia, a new collection of anecdotes and advice by female academics in Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Africa and the UK. While she acknowledged that some effort had been made to address gender imbalances, it was not enough without larger societal changes.

“Some traditional ideas and mindsets are still reflected in Asian higher education,” she said. “It’s good to provide childcare and have more money for research, but if that mindset doesn’t change, then we aren’t going to get there.”

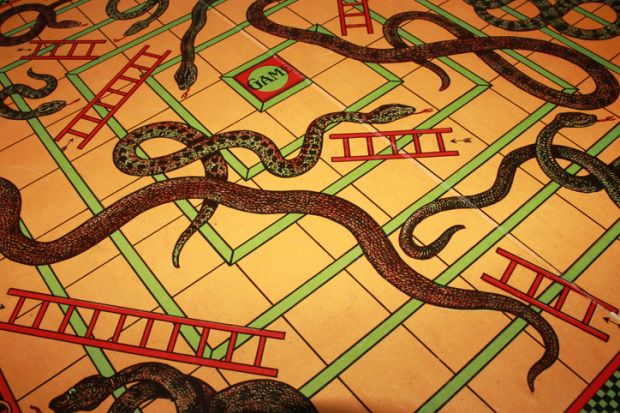

Dr Mahat compared a woman’s path in higher education to a board game filled with detractors and pitfalls.

“It takes only one snake in an academic woman’s snakes and ladders board to have a serious impact – for example, a redundancy,” she said. “In academia, you are only as good as your last publication or award, and your value goes up and down. But women also face a glass ceiling and a lack of confidence in navigating the academic world.”

Chin Ee Loh, an associate professor at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, also shared what she called her “super-slow, nine-year path” in academia as a mother of two.

During Covid, she said that working women spent “disproportionately more time on children”.

Part of her challenge was balancing generating enough academic paper citations to advance her career, with her larger goal of helping children, teachers and parents.

“Universities may value ‘academic books’, but my poetry anthologies actually help teachers teach reading,” she said.

“My key aim is not to publish papers, but to change [education] policy. So I put time into translating my research into infographics and more readable reports. I write opinion pieces for the media and produce a podcast,” she said. “So what if we want to move up the academic ladder? We have to make choices, and I chose what was important to me.”

She added that she benefited from having a female dean who “appreciated my other impact”.

Priya Goel La Londe, an assistant professor in HKU’s Faculty of Education and moderator of the event, said that there were some “signs on progress” for women in academia, but that change was “slow and incremental.”

“It’s no secret that women are under-represented in senior higher education roles across the world – and in particular in East Asia,” she said.