Reply all? Please don’t

It’s Monday morning, and you arrive in the office in a high fever after another parking nightmare. The photocopier is broken, so instead of preparing handouts for your 10am class, you decide to make a head start on the thousand or so emails in your inbox.

The faculty is going through a restructure (yes, another one!) and the interim dean has called for a new slogan: something bold and “cutting edge”. You need coffee. Curiously, your mug is missing, so you search out the miscellaneous cup that no one uses: the one with the chipped handle and a painted rose. You sit down at your desk.

An hour later, you’ve almost cleared your emails when a new notification arrives. The subject is: “re: The Future Begins Now!” Cathy, your colleague in design, has pitched her slogan to the dean and accidentally copied in the entire faculty. It’s an easy mistake, you think. You like Cathy. She was probably in a rush. You reason that it’s the end of semester and everyone needs a break. Especially Cathy. You delete the email.

But here’s what happens next. Karen, the payroll officer, replies: “Hi Cathy, I think you included me by mistake.” Fiona, also from HR, confirms: “And me.” A few minutes pass. Stefan, a PhD in women’s studies, takes the opportunity to show off his allegiance to the cause. He’s a feminist, you know. He replies: “#metoo”. You take a break from email.

In the kitchen, you take some time to look for your mug. You make a mental note to ask your colleague, Jim, if he’s seen it. You don’t trust Jim. He stole your third-year capstone module and reuses your lecture recordings. He’s also married to your boss.

When you return to your desk, Professor X, a supremely intelligent man with no idea how the internet works, has replied: “Please unsubscribe me from this list.” You close your eyes and think of a happy place. You picture yourself there, in the bottle shop.

Your daydream is interrupted by the noise of a chainsaw. Two men from facilities management are cutting down the tree outside your window. One of them waves. You have seven new emails. You delete them all. Just when you think it’s over, Cathy responds: “Please disregard my previous e-mail.” Another email immediately follows: “Cathy has retracted the email ‘re: The Future Begins Now!’ ”

You close the lid on your laptop. Jim appears in his Lycra bodysuit.

“Good morning!” he says smugly. “Coffee?”

Kate Cantrell is a lecturer in creative writing at the University of Southern Queensland.

The cold light of class

It took decades of experimentation – including by luminaries such as Edison and Tesla – to get things right. But by the 1950s, fluorescent lights had overtaken incandescents in terms of overall light produced (in the US, at least).

Their conquest of higher education has been especially complete. Look around you. As an academic with light-sensitive eyes (verging on photophobia), this annoys me no end. Sure, there may have been gains in efficiency and distributed luminescence, especially when measured prior to the advent of LEDs. But at what cost? Serious critiques on environmental and public health grounds aside (and these exist), who can disregard the decades of cumulative annoyance that fluorescent lights have produced among students, staff and faculty alike?

The small, Catholic liberal arts university at which I recently began teaching has a lovely stone-walled and wood-floored campus. During my interview visit the previous spring, I learned that students often compare it with Hogwarts (an association fuelled by the school’s griffin mascot). Before my start date, I couldn’t recall having encountered any fluorescents during that visit, and the thought of Harry, Ron, and Hermione practising spell-casting under a fluorescent buzz seemed inconceivable. So I envisaged an existence qualitatively different from that offered by the clinical blue-white, eye-straining spaces of the large public universities I had previously known. I dreamed of torch-lit classrooms and an office illuminated by the warm glow of a candle.

Of course, my chagrin at learning the grim truth is far outweighed by the joys of working with wonderful students and colleagues, and I recognise that fluorescent light may simply be a facet of academe that I have to accept. But that will not stop me from lighting my office with a warm-spectrum lamp from home. Or from taking a moment at the start of every class (non-winter ones at least) to switch off the lights and let the daylight in.

David Baumeister is an assistant professor of philosophy at Seton Hill University, Pennsylvania.

Missing collegial connections

“Oh, I don’t want to see colleagues after work.”

I hear that expression a lot from people working in the corporate world, but I have always been confused by the sentiment. Really? My gnawing irritation about academic life has forever been that I don’t get to see enough of my colleagues – most of whom are folks with whom bar-room conversations flow as smoothly as the wine.

I remember a colleague from Oxford once telling me: “I’m a lot likelier to meet my colleague from the next office at a conference in New Zealand or South Africa than in our own hallway.” I guess he was exaggerating just a bit. But I get the drift. Such a situation is even more likely if your institution is a commuter school in the penumbra of a big city, where all things happen and life sucks you in too deeply.

This has always been my predicament, having gone to grad school in the outskirts of New York City, had my first teaching job just outside Toronto and spent several years at a school a stone’s throw from San Francisco, before moving to my current position at a university on the perimeter of Delhi. The commuters and the on-campus folks dwell in different worlds, and never the twain shall meet.

I count my blessings that all my teaching is packed into two hectic days each week, leaving me with a universe of time for writing and research. But this means that I am lucky if socialising with colleagues occurs even at the end of semesters. Our long-running conversations have to be largely conducted via email, social media, op-eds, articles and books.

Once in a while we stare at one another, in scandalous delight, across the aisle on the same international flight. Sometimes we are even bound for the same literary festival or academic conference, booked on the same panel or at the same hotel.

“Ah, you’re teaching Tuesdays and Thursdays this semester,” they say to me. “No wonder we never see each other!”

Saikat Majumdar is professor of English and creative writing at Ashoka University, India.

The ‘hotbed of radical leftists’ myth

“Is it true”, a schoolteacher recently asked me, “that humanities academics are all communists, like Jordan Peterson says?”

“No,” I answered, truthfully. “Not even close.”

Australia has recently been through another conference season. At every session I attended, we historians were a long way from agreeing on our interpretation of the past and on its implications for our rapidly changing economic conditions in the present. If there is a socialist consensus, it must be happening in the other room, every time.

Moreover, our disagreements are important – this is why we go to conferences in the first place. Every time someone queries my interpretations, asks if I have considered another angle or suggests that I might profit from a new line of enquiry, my work becomes more robust. It is true that academics tend to lean left, but among historians, at least, it is far from universal. And the idea that we sit around agreeing with each other is ridiculous.

But the schoolteacher did not believe me.

“I didn’t realise it at the time, but thinking back to my study, all the academics were socialist,” he mused.

This was not the first time that I have had this conversation. The claim that academics are all socialists has become a motif among right-wingers seeking to lay blame for their perceived marginalisation.

But the claim is not only wrong but dangerous. It shuts down debate at a point in history when robust discussion about our future is essential. And for those of us committed to pushing thinking forward, it is really annoying.

Hannah Forsyth is lecturer in history at the Australian Catholic University.

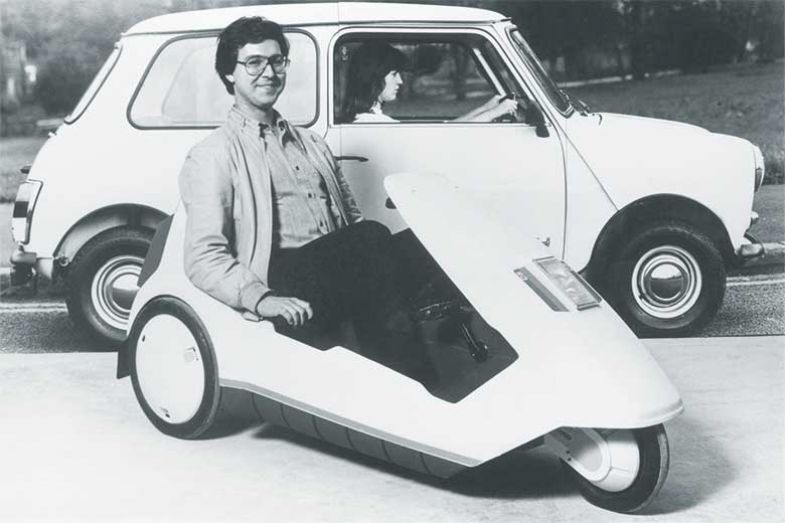

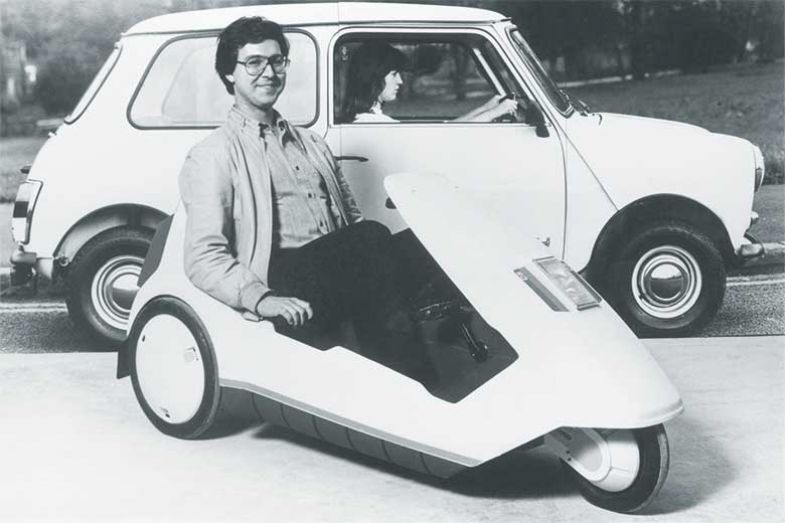

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Names over knowledge

At a relatively late stage in my life, I was drawn into academe, largely because of ideas. How wonderful, I thought, to spend your life developing new insights into problems and training young people to do the same. So I find it demoralising when visiting speakers are introduced with a list of journal titles in which they have published, instead of a brief summary of their research ideas.

But this is just one manifestation of academia’s ridiculous obsession with journal titles. Some managers seem not to care even whether a “four-star” article ever gains any interest or citations. If I designed a car that a handful of critics liked but that no one wanted to drive, would that also be deemed a mark of success?

Of course, this is part of the now-common culture of research performance management – tied, in the case of the UK, to the research excellence framework. Yet 25 per cent of the scoring in the 2021 iteration of the REF (up from 20 per cent last time) will be based on the impact of papers. So managers would do well to read the recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by the Nobel prizewinning economist James Heckman and co-author Sidharth Moktan, “Publishing and promotion in economics: the tyranny of the top five”, which shows that the majority of influential research in economics is found outside the most highly prized journals.

I’m not suggesting that I don’t always try to publish in good journals. Of course I do. But it is high time that all universities signed the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), which prohibits the use of journal impact factors in the assessment of scholarly research. To quote Heckman, the reliance on a few titles to screen talent “incentivises careerism over creativity”. And isn’t that just anti-intellectual?

Amanda Goodall is senior lecturer at Cass Business School, City, University of London.

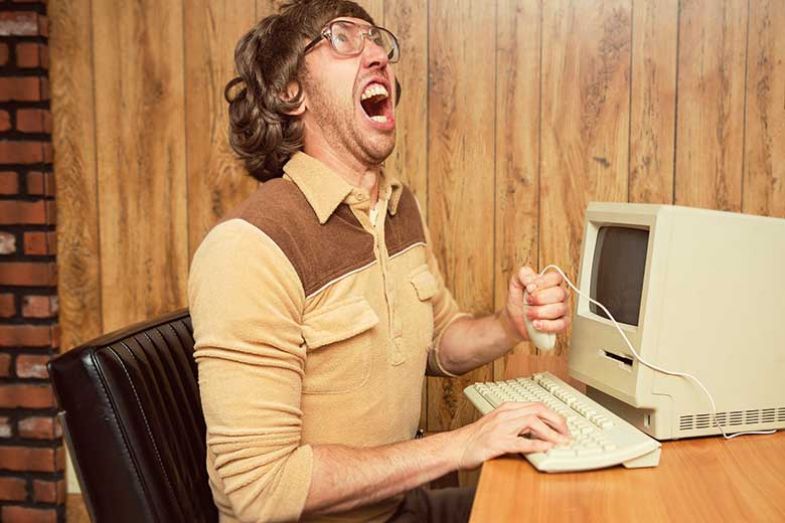

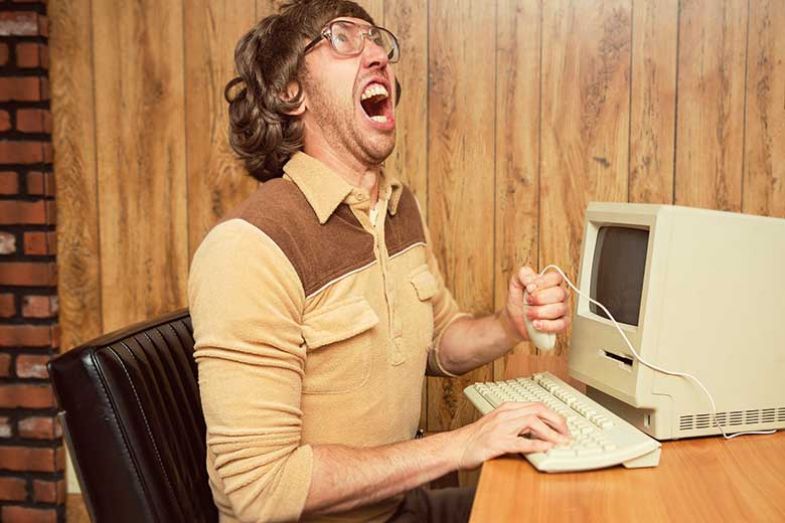

Source: iStock

Source: iStock

Demanding and thankless peer review

One thing I’ve been particularly peevish about recently is the thankless process of peer review.

My annoyance is triggered by the contracting timescales within which you are expected to produce a review: now usually only two weeks from acceptance of the review invitation. This is exacerbated by the relentless, automated emails that start hitting your inbox within a few days, providing a “gentle” reminder that your review is due in one week, three days, today, three days ago – and so on.

And your reward for holding off all your teaching, supervision, admin and (if you’re lucky) research commitments to give the manuscript due consideration, do any necessary background reading and write a thoughtful critique? A similarly automated “thank you” email from the review system.

Of course, you may feel satisfied at having contributed to the safeguarding of science, as well as having completed a key “service to discipline” requirement for promotion. But mostly, reviewing remains a thankless task – notwithstanding some nascent initiatives to improve recognition for it, such as Publons. The icing on the cake is that while we do all this for free, we face increasing costs when it comes to publishing our own work, particularly if we want our paper to be open access. Coloured pixels are an additional expense on top of that; no wonder academic publishers report greater profits than ever.

As I pondered what to do about the review invitation I received in the week before Christmas week (due, of course, 14 days later: New Year’s Day), I couldn’t help but picture the big academic publishers as modern-day Ebenezer Scrooges, who reap all the profits from our hard labour while keeping science under lock and key from those who need it most.

Clare Kelly is Ussher assistant professor of functional neuroimaging at Trinity College Dublin and adjunct assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

To whom it may concern…

Near the end of every academic term, I have to set aside an afternoon to write reference letters for students going on to graduate school. It is a chore that I hate.

It’s not my students who frustrate me. I don’t mind saying nice things about individuals I want to see succeed in life. It’s the system that I hate.

The corporate world gets it. They primarily request references, not letters of recommendation. This often results in phone calls with my students’ future employers. The phone calls take just a few minutes and allow me to be candid, open, honest and often warm in how I talk about my students. I can talk in a way in which the human resources professional on the other end of the line can hear my honesty. Letters for reference, however, are full of lies and half-truths. No one trusts them and no one should – if they actually read them.

Academics are, by and large, decent human beings who have affection for their students. Even the screw-ups. I have never read a reference letter that says, “Steer clear of this one!” Instead, everyone I know has templates they use to make the most disappointing of students sound palatable.

We need a new system. Two questions. “Is this student annoying?”, and “Is this student capable?” Yes or no. That’s all anyone needs, or actually wants, to know.

Darren L. Linvill is an associate professor in the department of communication at Clemson University in South Carolina.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Academic immunity to word limits

Opening an email and finding yet another abstract of more than 500 words, I was beginning to second-guess myself, so I went back to the call for papers that I had posted. “We invite abstracts of approximately 200 words”, it said. Well, then. I had clearly brought this on myself.

Approximately is an invitation to academics to do what they like, when they like. Given how few are able to meet fixed deadlines as it is (I include myself, as I guiltily look at the pile of well-overdue books for review in my home office), I had anticipated that on the date I had set for abstract submissions I would receive several emails asking for a few days’ grace. Having not organised a conference in some time, however, I had forgotten how many of my fellow academics would ignore not only deadlines but also basic instructions.

A 200-word abstract attached as a Word document sent to a specific conference email address: very straightforward, right? Instead, I got 500-word abstracts written directly in the body of the email, sent to my work account.

None of this is a big deal as a one-off, of course. But as a harassed early career researcher organising an event single-handedly, it was hugely time-consuming to deal with these little niggles dozens of times over. If you write an overlong abstract, or leave out your contact details, or submit it in a hard-to-download format, you are making extra work for a colleague – and there’s nothing collegial about that.

The next time I arranged a conference, I asked for abstracts of 100 words maximum. Of course, only around half the submissions complied with that request. But it did mean that 90 per cent of submissions topped out at under 250 words. It’s a start, I guess.

Rachel Moss is a lecturer in late medieval history at the University of Oxford.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Watch your language!

I like and believe in universities. Yet there are two things that really bug me about their modern British manifestation.

First, why can’t students understand that sentences cannot be joined by commas? Who teaches these students before they show up? “Professor Oswald complained to the student about her grammar, the professor suggested she work harder, the student was grumpy, her friends gave her beer.” This is not English, for goodness’ sake.

What has happened to grammar and clarity of writing? And here I am not talking about the propensity of The New York Times or The Economist to start sentences with “and”. Nor am I talking about a tendency for a great writer occasionally to skip, with impish delight, some grammatical rule. I am talking about elementary errors by otherwise brilliant students. In my experience as an examiner for many of the UK’s fanciest universities, at least a quarter of the students graduating with first-class honours cannot write in a way that would have earned them a decent O level in English in the 1960s.

My other gripe relates to so many central administrations’ habit of issuing forms in morale-sapping managerialist jargon. For instance, one elite UK research university I know conducts an annual performance review of its professors. Fine. Yet guess the first question on the form. Is it about how the professor’s ideas have changed their discipline, or about their world-class publications during the year, or about the students they recently inspired? No. It is: Highlight where and how you have personally contributed to the creation and maintenance of an environment of dignity, respect and inclusion in your Department.

I imagine this question was made up by someone with a good heart but no understanding of research universities. Professor Oswald once went for dinner at Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons. That does not mean he is qualified to oversee the annual performance review at that celebrated Oxfordshire mecca of gastronomy. His questions would send the chefs screaming from the restaurant and bankrupt the place.

Andrew Oswald is professor of economics and behavioural science at the University of Warwick.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Keep it short and sweet

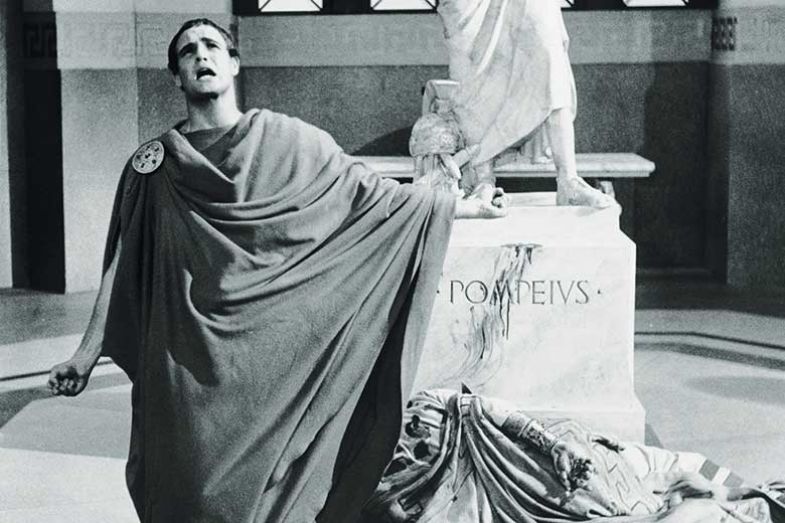

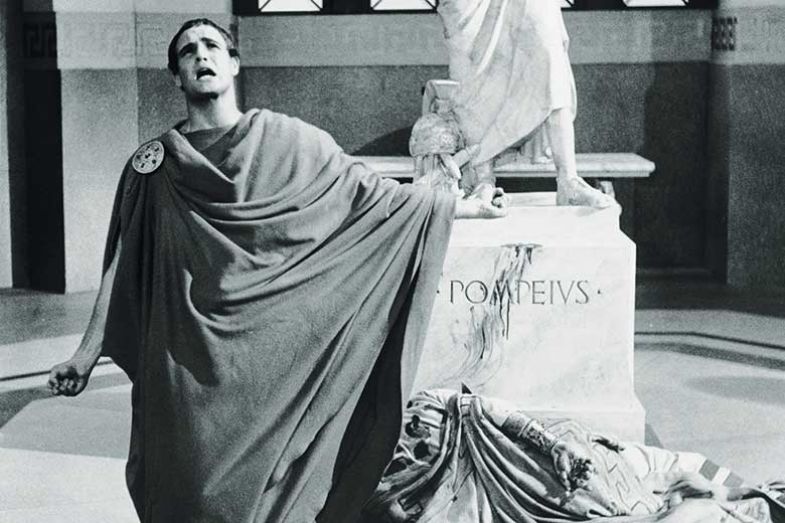

When Shakespeare’s Mark Antony stepped forward to speak at Caesar’s funeral, he did not begin with: “I know time is short, so I’ll keep this brief.” More remarkably still, his speech nevertheless was brief.

Hardly a day goes by at my university without some sort of oration, and, over the years, I’ve noticed that those who say “I’ll keep it brief” never do. I’ve concluded that the enlightened few who are capable of being brief are those who have realised that spending the first few moments talking about the importance of brevity doesn’t help the cause.

But false promises to be economical with listeners’ time are by no means the only examples of the lax and sometimes downright paradoxical use of language by some senior university staff. “Working parties” are talking shops. “Collaborative networks” are about locking some people in – and, therefore, locking everyone else out. The phrase “student success” makes me worry about failures, in the same way that, in the wider world, seeing a “community street mural” makes me worry that I have strayed into a bad neighbourhood.

Hiding the bad news is a time-honoured tradition designed to maintain enthusiasm and momentum, but real action can be better driven by direct language. I’d much more willingly lend my ears to talks that began with the regional equivalent of “friends, Romans, countrymen, I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him”.

Merlin Crossley is deputy vice-chancellor academic at the University of New South Wales.

Too carefree to care about publishing

I remember her well: smart, studious, systematic. She could put a theoretical argument together like a jigsaw puzzle. Her number-crunching was exhilarating. Her discussion section could blow your mind with its insights. I gave her master’s thesis top marks and raved about her work at graduation. During the celebration afterwards, I popped the question. Would she like to publish it with me? You know, in an actual academic journal? Let all that beautiful knowledge breathe free, and not rot away in a thesis archive? She declined.

The years went on. It didn’t happen often, but once in a while, I’d see that brilliance again, and ask the student to participate in the honour of academic publication. Usually, they’d decline. Worse, they’d agree, then stop answering emails. They had a trip planned, or an internship or job lined up. They were looking ahead to a future in which publishing in a journal wasn’t important. They were leaving the university behind, while I was stuck inside, determined to squeeze every drop of knowledge from our months of research and supervision. How could they not see that a degree just wasn’t enough, and that all that work was for nothing if they didn’t publish it?

I remember myself at 23: freshly graduated and soon heading abroad. My thesis adviser sent regular emails reminding me to get my article in shape before I was distracted by life. But I’m going to Amsterdam, I thought. I’ve got to enjoy my summer, not write another boring article.

What was wrong with me? I’m still flabbergasted.

Janelle Ward is an assistant professor in the department of media and communication at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Source: Getty

Source: Getty

Lose the acronyms ASAP! OK?

I have been at my university for several years, but the first couple were spent irritably googling various three-letter acronyms that we are all expected to know. Even Google didn’t know most of them, requiring me to timidly ask more senior colleagues what they meant.

I am starting to get on top of most of this specialist knowledge now, and I am probably turning into one of those irritating colleagues who use acronyms without noticing. However, every new academic year or new post of responsibility (PoR) brings with it a suite of new buildings, forms, degrees, support groups, metrics or timescales that we need to learn.

Some are fairly straightforward, and easy to crack (although I’m not sure about the necessity of shortening Science Faculty to SCI FAC). However, some are just impossible to decipher – especially when they change so often. As soon as you learn that REN stands for “research and enterprise services”, “enterprise” has become “innovation”. But the new acronym, RIN, still bafflingly omits the S for services.

The DoS office (dean of students; not to be confused with the dean of science, who has recently changed into the pro vice-chancellor for science – PVC) has recently morphed into SSS (student support services). I have to be careful not to mix up LTs (lecture theatres) with LTS (learning and teaching service), and the SP (sports park) with SpLD (specific learning difficulties).

It’s impossible to keep up. We’d all be better off communicating like normal human beings. IMHO.

Jessica Johnson is a lecturer in geophysics at the University of East Anglia.