Millennial rapper Professor Green may have an academia-inspired alias but that is not a reflection of any double life as a scholar. Like many white, working-class men in the UK, he did not go to university; he was brought up by his grandmother on a council estate and left school without any qualifications.

“For middle-class families, your education is your life,” he said earlier this year, ahead of the broadcast of his documentary Working Class White Men, which explores, among other issues, why boys from poor white communities are the least likely demographic group in the UK to go to university. “For working-class families, in some instances, school is just school. You are not expected to do very well. You are expected to get out and do a job and earn.”

While almost half of young people (49 per cent) are expected to enter university by the age of 30, according to recent government statistics, the gender gap has widened, with the share of women in that cohort estimated to be 11.9 percentage points higher than the share of men. In 2016, former universities minister Jo Johnson said that just 10 per cent of white boys from the most disadvantaged backgrounds progress to higher education.

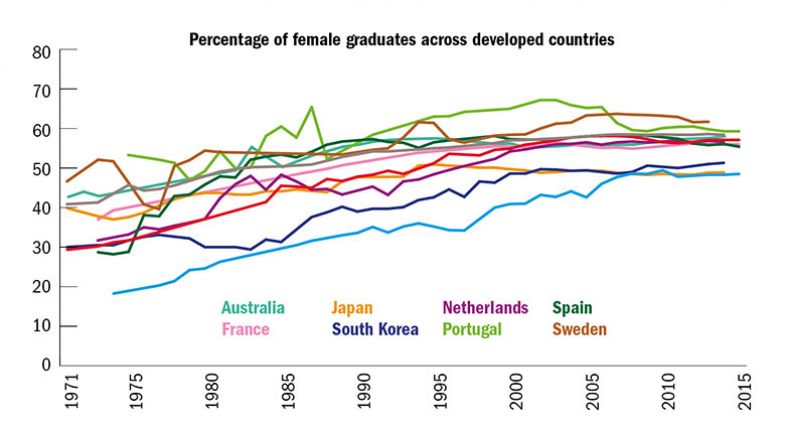

Meanwhile, latest figures from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation show that 57 per cent of students who completed higher education programmes in the UK in 2015 were women, a figure that has risen year-on-year since 2011 and has been above 50 per cent since 1995. In January, the University of Oxford announced that it had offered more undergraduate places to British women than men last year, for the first time in its history.

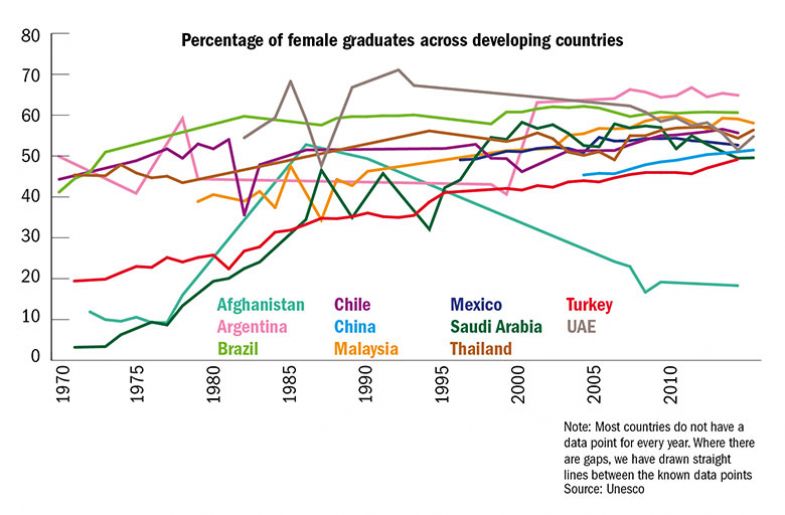

The ever-increasing flow of women into higher education is by no means a phenomenon that is confined to the UK. The Unesco data show that it common across every region of the world, and every stage of national development.

Just 47 of the 160 countries and territories that have recently published statistics had a higher share of male than female graduates in their latest graduate cohort. The British Virgin Islands is the most female-heavy territory, with women making up 75 per cent of its graduates in 2015. At the other end of the scale is Afghanistan, with just 18 per cent of graduates in 2014 being female. Interestingly, that figure was 53 per cent in 1986, but had fallen to just 24 per cent by 2006, coinciding with the Taliban’s ban on female education.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and co-author of the 2016 report Boys to Men: The Underachievement of Young Men in Higher Education – and How to Start Tackling it, warns that, although he does not think the UK has yet reached this point, both men and women could be put off from going to university if campuses become female-dominated. And he highlights several reasons for the UK’s growing gender disparity. These include the fact that the gap between the average earnings of people who do and do not go to university is larger for women than for men; female-dominated careers such as nursing and teaching now require a degree; and girls do better than boys at school.

For Mary Curnock Cook, former chief executive of UK university admissions service Ucas, that last explanation is particularly compelling. “For some reason, boys are underperforming at pretty much every stage of education and it accumulates at each stage,” says Curnock Cook, who has warned that the gap between male and female applicants could, on current trends, eclipse the gap between rich and poor within a decade. “By the time it comes to applying to university, there are just many fewer boys [qualified to do so]. That’s not just school-leavers but in older age groups as well.”

This trend was dubbed the “Martha Effect” in a recent South African study, based on the idea of the “Matthew Effect”, whereby the rich get richer. But Curnock Cook says that, while the phenomenon is well known, “there seems to be very little work to understand why that happens and still less to think about what solutions need to be put in place. I still find it quite extraordinary that there is no government policy that is saying this is a problem and we need to address it”.

One potential explanation for this silence, Curnock Cook suggests, is that “it’s quite unfashionable to have views about the underperformance of men”. While there are numerous initiatives aimed at getting more women into science, technology, engineering and mathematics, little attention is paid to the much greater domination by women of fields such as nursing, teaching and social work, she says.

“The prevailing narrative for many decades has been about how women are disadvantaged against men, not the other way round,” she says. “I don’t see much evidence of people [treating this] as a societal issue, which I think it is.”

Equality issues aside, she adds, there are many business reasons why universities should want to tackle the issue because if men participated at the same rate as women “that would be an extra 40,000 people in higher education. To me, it’s a huge unmet potential issue and it’s a huge market issue”.

For Garth Stahl, senior lecturer in education at the University of South Australia, the low share of white working-class boys in Western universities should be seen in the context of the “crisis” of working-class masculinity that he perceives to have resulted from the post-industrial elimination of trade work, which was previously seen as “respectable employment” in such communities. The fact that higher education tends to value “middle-class and upper-class masculinity” means that many boys from disadvantaged backgrounds struggle to find their place there.

“Working-class culture doesn’t fit well in a university context because university is arguably about being the best of the best, whereas working-class culture, especially in the UK, is about fitting in, where no one is better than anyone else,” he says.

The Centre for Young Men’s Studies at Ulster University has conducted extensive research on this topic, in a project called Taking Boys Seriously. Brian Murphy, director of access, digital and distributed learning at the university, says that researchers on the project, which is now funded through widening access funds, are beginning to ask whether there is “something about the education system that is not recognising the barriers to educational attainment for boys from disadvantaged communities, particularly from year 10 onwards when their developing masculinity and their community influences add a new dimension to educational engagement.

“More affluent groups tend to have the social capital to succeed,” he says.

Similar factors could partly account for the gender disparity among students in other countries: even those in which discrimination against women is common. According to the World Economic Forum, the United Arab Emirates, Syria and Lebanon are among the worst nations for gender equality, yet women make up 55 per cent of the most recent recorded graduate cohort in the UAE and Syria and 56 per cent in Lebanon.

Natasha Ridge, executive director of the Sheikh Saud bin Saqr Al Qasimi Foundation for Policy Research, based in the UAE, says that in highly patriarchal countries, boys from upper-class families may enter the workforce through family connections, while historically popular, male-dominated careers in the Middle East did not previously require a degree. This has now changed for the police and local government, but “the school system hasn’t really caught up with that and I think there’s a lack of information [about that] for boys with a lower socio-economic status,” says Ridge, who co-authored the World Innovation Summit for Education report The Challenges and Implications of a Global Decline in the Educational Attainment and Retention of Boys.

In addition, she says, while traditionally women have been largely excluded from the workforce in many parts of the Middle East, university has long been considered a “safe space” for them to go after school, particularly in nations where education is gender-segregated. There is a “premium” placed on “the educated housewife”, she says: “A woman with higher education is [seen as] more marriageable, a better mother, and that’s across the whole Middle East.”

As the region sees what Ridge calls a “big shift” in the share of women entering the workforce, there are also more professional reasons for females to acquire degrees. Surprisingly, women in countries with low levels of gender equality are more likely than those in more equal countries to gain STEM degrees, according to a recent study that drew on data on 475,000 adolescents across 67 countries.

Gijsbert Stoet, professor of psychology at Leeds Beckett University, who co-authored the research, says one explanation is that the value of a STEM degree is higher in less liberal or developed countries.

“In a country that is poorer…you might be more interested in a career where you can make more money,” he says. “Whereas in the West there are more job opportunities in general that offer similar salaries, so women probably have more choice.”

Liberal mores in gender-equal countries may also allow personal preferences to be expressed more strongly, according to the study, which found that in nearly all of the countries analysed, girls tended to register a lower interest in science subjects. And while boys’ and girls’ achievement in STEM subjects was broadly similar, science was more likely to be boys’ best subject, it found.

In some Asian countries, the rise in the number of female students could also be partly explained by an increase in female-only universities. In India, female graduates outnumbered their male counterparts for the first time in 2014, according to Unesco, with the latest (2015) figure for female participation at 50.5 per cent: up from just 30.2 per cent in 1988. Over that same period, women-only universities mushroomed. About a decade ago, India’s regulatory body, the University Grants Commission, announced an additional 800 female-only institutions, on top of 2,500 that already existed, says Kristen Renn, professor of education at Michigan State University and author of the 2014 book Women’s Colleges and Universities in a Global Context.

Renn says that these institutions are particularly attractive to “very conservative” Muslim and Hindu families in rural areas, where young women do not have the opportunity to live at home while studying. Female-only institutions are also an attractive option for widows, who are a marginalised group in society but can benefit from evening courses, she adds.

Female-only institutions also help to address the discrimination that female students sometimes experience at India’s co-educational universities. Several of Renn’s interviewees “talked about sexual harassment and discrimination”; in one case a woman’s lab equipment was destroyed overnight in a gender-related attack. In another case, a female academic in Kenya revealed that she was unable to work late or participate in any evening activities on campus because Nairobi is not safe for women at night.

Female-only universities have “a very strong emphasis” on leadership development and entrepreneurialism, says Renn. And while such institutions have declined rapidly in the UK and the US as educational and employment opportunities for women have become more equal, Renn is sceptical that the tide will turn against them any time soon in developing countries.

“We’re in a wave globally where there’s this very strong conservative, fundamentalist backlash [against women] that I think would slow an otherwise moderate change towards most institutions becoming co-educational,” she says. “Then there are also cultures, geographies, political systems where the opportunity to be at an all-female campus for three years, to really focus on building resilience and leadership, is really important.”

Elsewhere in Asia, Munir Shuib, deputy director of Universiti Sains Malaysia, says that while there are more women than men in Malaysian universities, male students dominate in polytechnics and community colleges.

“This indicates that the trend occurs not by chance but by choice. Could it be that the universities are not able to cater to the learning needs of the boys?” he asks, adding that it has been argued that the curriculum in his country is biased towards girls’ needs.

“Generally, boys tend to be more practically oriented, whereas girls tend to be more theoretically oriented. So, perhaps a choice should be given as to how the students want to be assessed,” he suggests.

But Ana Martínez-Alemán, associate dean of faculty and academics at Boston College’s Lynch School of Education and an expert on the impact of gender on learning, says that research suggesting that women learn differently from men is “highly contentious”.

She also rejects the idea that the increasing enrolment of female students means that universities are “now pitching everything to women”. “The changes that we [have] seen probably since the late 1980s is the impact of feminist and constructivist pedagogies that are fundamentally just good pedagogies – men do well with them too,” she says. These trends include more interactive, inductive and workshop-based teaching – although she acknowledges that some teaching techniques that “pit students against each other”, such as the use of clickers to collect student responses to questions, “tend to be more favoured by men”.

Martínez-Alemán adds that the general trend of higher university dropout rates among men could be because “women tend to underreport their academic potential…when they forecast their academic performance in college, and boys tend to oversell themselves”. This means that “a lot of young men get a very rude awakening [when they get to university] and their self-worth hasn’t really been ready for that.”

So what can be done to address the gender imbalance? Hepi’s 2016 report suggested introducing foundation years for boys, of the sort already offered to international students, to reflect the fact that their brains mature later than those of girls. Another idea is a “Take Our Sons to University Day”, modelled on the US-initiated Take Our Daughters to Work Day (which now includes sons, too).

“Probably the single thing that shocked me most when we put the report together was how few universities mentioned gender in their access agreements,” Hillman says. And even when universities do “try to grapple with this problem, they sometimes go for quite hackneyed and stereotyped solutions that slightly caricature men, just as women have often been caricatured in the past”. An example is access programmes run in collaboration with local football clubs.

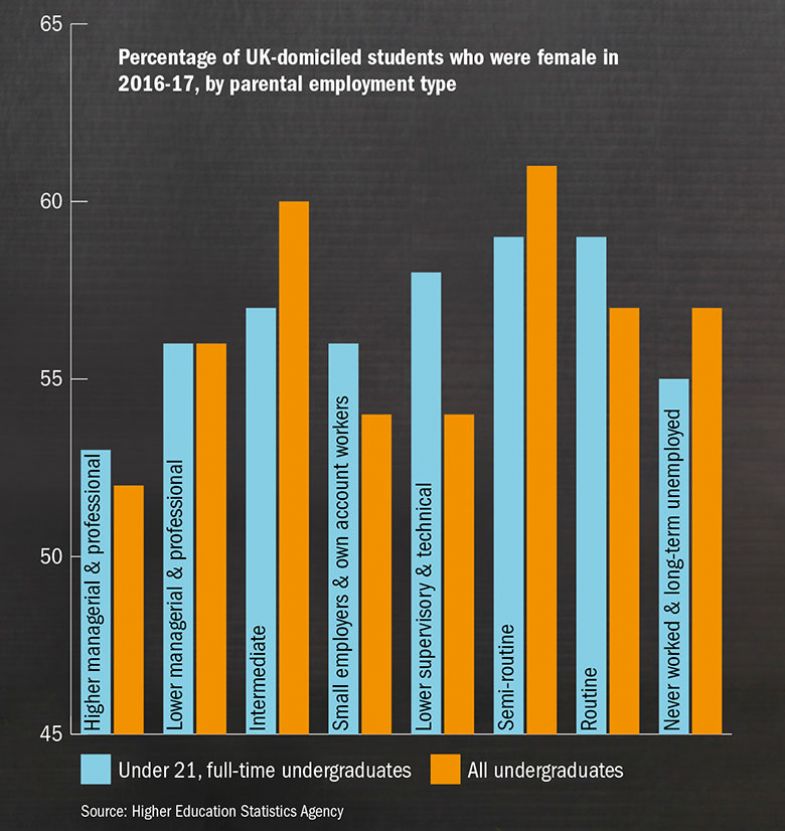

When asked about male under-representation, commentators often default to talking about working-class boys. However, in the UK, at least, the issue is common across all demographic groups. Figures for 2016-17 from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that even among full-time students under 21 whose parents have “higher managerial and professional” jobs, women account for 52 per cent of the cohort. That proportion rises steadily as skill levels decrease, reaching 59 per cent among young undergraduates whose parents have “routine” jobs. However, it falls again, to 55 per cent, among those whose parents are long-term unemployed. And while female representation among undergraduates as a whole is lowest among those from the most privileged backgrounds (52 per cent) there is no clear trend across other skill levels.

One university that is working hard to increase its proportion of working-class boys is the University of Bath – despite the fact that 54 per cent of its student cohort is already male.

Mike Nicholson, the institution’s director of student recruitment and admissions, says that Bath has taken a two-pronged approach: engaging with white, working-class boys at primary school and adjusting its admissions support to help those who need it beyond the point of application.

“Research suggests that getting students very early is key,” he says. “White, working-class boys in the transition between primary and secondary school can get demotivated by education.”

According to Stahl, Australia’s 2008 Bradley review of higher education resulted in the government pledging that 20 per cent of undergraduates should be from low socio-economic backgrounds by 2020. In 2014, it provided funding incentives to help achieve this by proportionally distributing money to universities based on their share of students from such backgrounds, he says.

In 2016, the Scottish Funding Council set targets for its universities to stop “extreme gender imbalance”, ruling that by 2030 no courses should have more than three-quarters of students of one gender. In the same year, the UK government issued fresh guidance to the Office for Fair Access demanding that universities work more closely with schools in poorer areas, targeting white working-class boys in particular.

Ridge says that her institute in the UAE has several programmes focused on tackling the gender issue, one of which is modelled on an Australian programme called Hands on Learning, which aims to prevent pupils dropping out of school: “What we really stress is being responsible for yourself: [the idea] that you can control your behaviour and giving boys strategies for how to manage their emotions. And at the same time giving them a sense of competence,” she says.

But she suspects that the proportion of female students in the Gulf region is unlikely to decrease any time soon.

“There’s still a lot of focus on further improving the status of women…I haven’t seen any programmes addressing the issues of [low participation of] males,” she says. “I find that quite disturbing because…we fought for women’s rights and for equal access and [for women] to be given an education that was as good as [that given to] males. By the same token, we should be ensuring that males now have that same opportunity – especially since…we’re talking about a specific group of males: those coming from more deprived backgrounds, who can go on to pose other risks for society if they’re…marginalised.”

Schools across the world “need to do a better job of being welcoming for boys and of letting boys be whatever it is that they feel they want to be – not in a way that’s destructive but being supportive of them, helping them to find educational strategies that suit them,” Ridge says.

As for universities, heeding calls for them to lower entry standards for applicants from poorer backgrounds could boost male participation. However, the policy is highly controversial, with right-wing newspapers dismissing it as “social engineering” and the chief executive of the Russell Group, Tim Bradshaw, warning that it risks setting up those students to fail.

Shayna Medley, a Skadden fellow with the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBT and HIV Project, is dismissive of the idea of positively discriminating in admissions in favour of men. In a paper published last year, while she was a JD candidate at Harvard Law School, she claimed that it is an “open secret” that there is already a “preference for male applicants”. “Affirmative action for men” would amount to “sex discrimination, and an unspoken cap on female enrolment…reminiscent of the racial and religious quotas of the past”. But, in contrast to the long history of explicit discrimination experienced by racial and religious minorities, “men as a whole have not been historically excluded from accessing higher education on account of their sex alone”, Medley writes.

In a 2006 opinion piece in The New York Times, Jennifer Delahunty Britz, former dean of admissions and financial aid at Kenyon College, a private, liberal arts university in Ohio, admitted that female applicants had to have stronger applications than their male counterparts because of the gender imbalance.

“The reality is that because young men are rarer, they’re more valued applicants,” she wrote. “We have told today’s young women that the world is their oyster; the problem is, so many of them believed us that the standards for admission to today’s most selective colleges are stiffer for women than men. How’s that for an unintended consequence of the women’s liberation movement?”

Meanwhile, the revelation in 2012 that female prospective students in China were facing higher entry barriers than their male counterparts led to protests. According to Chinese news reports, the practice began as early as 2005, in response to the rising numbers of women getting into universities and the fact that women were starting to outstrip men in some subject areas. Latest figures from Unesco show that 51.5 per cent of graduates in China were female in 2015, despite the fact that the country was home to 33 million more men than women in 2014.

Ellen Pugh, programme manager (policy) at the Equality Challenge Unit, says that while positive discrimination in favour of under-represented groups is illegal in the UK, “positive action” is not.

“Positive discrimination would be giving a place to a student because they are from an underrepresented group, full stop. Positive action is looking at the ways you can support underrepresented groups through the applications process and prior to that,” she says.

But the contentious nature of male under-representation among undergraduate cohorts – together with the focus on female under-representation among senior academics and university leaders – may help to explain universities’ lack of progress in this area.

Martínez-Alemán says that another factor is men’s reluctance to respond to more women entering previously male-dominated fields by, themselves, entering previously female-dominated ones. This is because, according to the cultural discourse, “for men to engage in women’s work is feminising them...It’s emasculating”, she says – particularly as such work is often lower-paid.

As for white, working-class males specifically, Ridge laments that “there’s nobody mobilising behind them”.

“It’s not a very popular cause,” she notes. “Males in general have been lumped into the whole concept of male privilege. But not all males are privileged.”

For her, boosting the numbers of disadvantaged boys in higher education is something everyone should support: not least women.

“Having well-integrated boys is a win for women,” she points out. “They treat women better; they’re respectful: they value women. These are outcomes everyone wants in society.”

后记

Print headline: Why is Martha doing better than Arthur?