When Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth in 1961, the Soviet Union was triumphant. And although the country’s capitalist rival, the United States, won the race to put a man on the Moon, science and technology remained one of the spheres in which the Soviet Union led the charge to demonstrate the superiority of communism to capitalism.

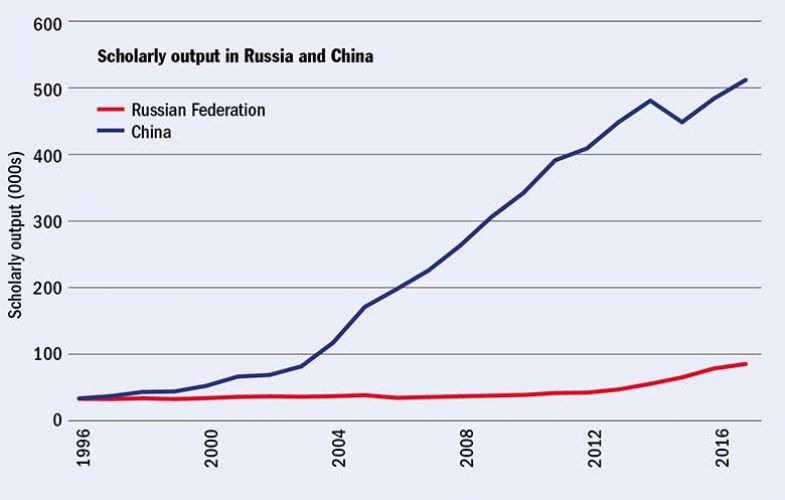

Yet, since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia’s underwhelming scientific trajectory is put into sharp perspective when compared with the progress of its former communist neighbour, China.

Despite their both being included in the BRIC group of major emerging nations identified by former Goldman Sachs chairman Jim O’Neill in 2001, the gulf that has opened up between them when it comes to higher education is astonishing.

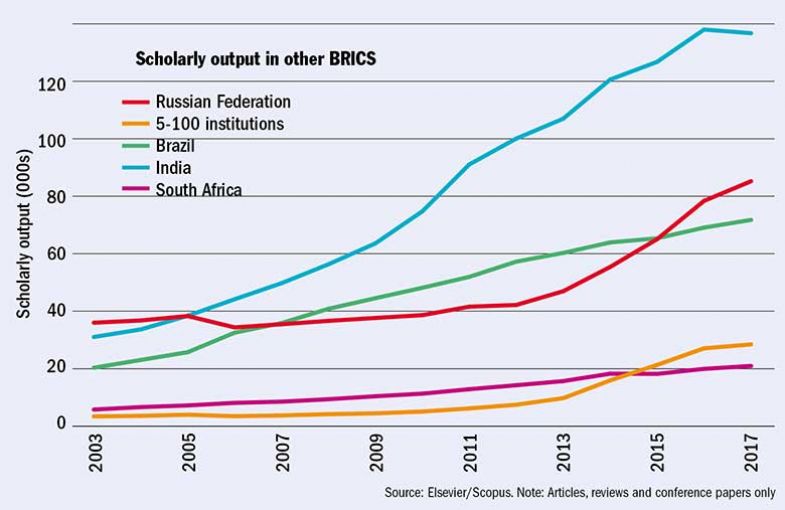

In 1996, both were producing around the same amount of research indexed in the Scopus bibliometric database: about 30,000 articles a year. Fast forward to 2017 and China published more than 510,000 academic articles and conference papers, compared with Russia’s 85,000. Indeed, Russian research output hardly moved at all for 10 years, leading it to fall behind other BRIC nations India and Brazil, too, by 2010 (although still ahead of South Africa, which joined what is now the BRICS grouping in 2010).

Admittedly, Scopus does not show the complete picture as it does not fully reflect the large amount of research that is published in Russian. But, at the very least, it is clear that other BRICS countries have been quicker to plug themselves into the English-speaking global science ecosystem. And Russian universities have languished in international rankings as a result.

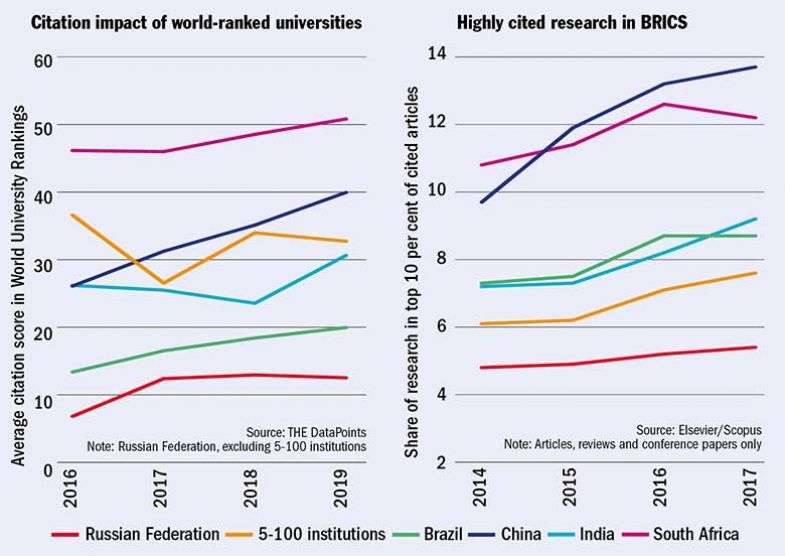

However, in the past five or six years, something seems to have changed. From 2012 to 2017, Russia’s scholarly output in Scopus more than doubled (taking it back past Brazil), and its representation in Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings has risen from just 13 institutions out of 800 in 2016 (1.6 per cent of the total) to 35 out of 1,258 (2.9 per cent of the total) in the most recent rankings, for 2019.

Stamp of approval: Dimitry Medvedev speaks at the opening ceremony for a technopark of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology

The major change in Russian policy in that time has been the launch of Project 5-100 in 2013. In this, 21 universities have been selected – an initial 15, then six more in 2015 – through an open competition to receive up to 1 billion roubles (£11.6 million) a year in an attempt to propel five of them into the top 100 of global rankings by 2020. The universities were chosen after presenting proposals – or “roadmaps” – on how they aim to improve their international standing. Their progress has then been judged against these roadmaps and also performance indicators drawn up by the project. Not every university receives the same amount of funding – those deemed to be performing well have been rewarded with additional money.

The eponymous goal of the project looks a long way from being met: the only Russian university in the latest top 200 is Lomonosov Moscow State University, at joint 199th. Moreover, Lomonosov is not a 5-100 university: the highest ranked of those, the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, is in the 251-300 band. However, the data suggest that 5-100 institutions have been improving fast on some important markers. For instance, from 2012 to 2017, the universities – 18 of which make the latest ranking – have quadrupled their research output indexed in Scopus, from about 7,000 to 28,000 articles. This takes them above the whole scholarly output of South Africa.

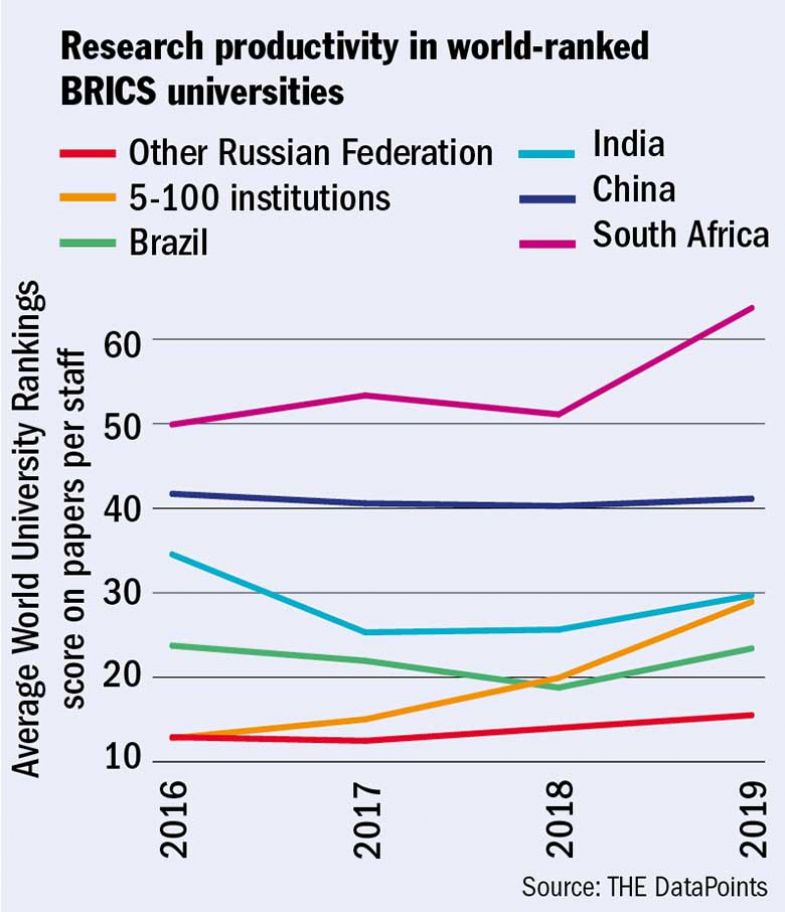

Their growth in research productivity has been especially striking. Output per academic for 5-100 universities in the ranking has been racing ahead of that of other ranked Russian universities. It has also passed that of Brazil and is almost on a par with that of India.

So is 5-100 an example of a government-imposed excellence initiative that is working? And what would that really mean? Is it raising the standard for all Russian institutions or creating a two-tier system? And what is the future for the project now that the original 2020 deadline is round the corner?

Andrei Volkov is deputy chairman of the 5-100 governing council, a panel of government officials, academics, business figures and other experts from Russia and around the world that oversees the project and advises the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education on where money should be spent. As a nuclear physicist and former university vice-rector, Volkov has seen the Russian system both before and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and he firmly believes that 5-100 is the “most influential reform” of the past 20 years in Russian higher education.

Key to its success, he says, has been ending the separation of teaching and research, by bringing universities – which were traditionally teaching-focused – together with centralised research institutes, primarily the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS).

Churning it out: productivity

“In Russia, there were no universities at all: just training institutions, [albeit ones of] extremely high quality…The shift from being a training institution up to be a researchbased institution is a cultural revolution in my country,” he says.

In practice, this shift has meant RAS research units becoming much more integrated with universities, through mergers, increased collaboration or researchers being given joint appointments.

Igor Chirikov, senior research fellow at the Center for Studies in Higher Education at the University of California, Berkeley, has looked in detail at how the 5-100 project has changed Russian universities, and he agrees that this shift has been important. “We had a sector of universities that had no historical mission to do research and investing through the 5-100 project made at least a portion of these universities more research-orientated,” says Chirikov, who was previously vice-rector at the Moscow-based Higher School of Economics, one of the highest ranked 5-100 institutions.

“Right now universities and the [RAS] are working much more closely than they did before,” he agrees, noting that a similar phenomenon is evident in Germany and China, where Max Planck Institutes and institutes of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have also become more integrated with higher education.

Nations with publications: scholarly output across the BRICS countries

The 5-100 programme has also led to more science that was previously published in Russian through the RAS becoming “visible” to international scholars by being published instead in English-language journals, Chirikov adds.

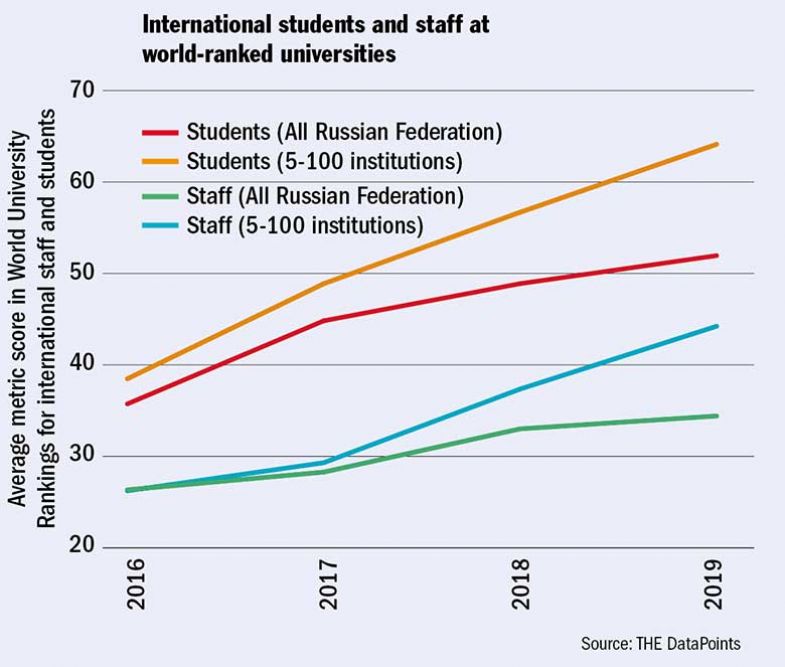

Another explicit aim of the project has been about placing the universities on a more global footing, by increasing international staff and student numbers. The data suggest that this push, too, has had an impact, with world-ranked 5-100 institutions improving more quickly than Russian universities as a whole on these metrics.

However, there are important caveats to this. On students, Philip Altbach, founding director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College and a member of the 5-100 advisory council, points out that “international students” in Russia also include those from former Soviet republics.

“The numbers that are not from the former Soviet Union have been growing, I think, but modestly. They are a small part of the total,” he says.

Altbach says that the 5-100 universities are “concerned about that. They are happy to have these folks, in part because some of them are paying higher tuition [fees]…but they really want to diversify where the international students are coming from.”

Meanwhile, Russian institutions’ efforts to recruit more international staff have been hampered both by the language barrier – most potential overseas recruits will not know Russian – and by drops in the value of the Russian rouble, which have made salaries unattractive compared with those available abroad.

Chirikov has also written about how the drive to quickly produce universities that are similar in their global outlook to those in Europe or North America has led to “parallel” structures on some campuses for overseas staff recruitment and retention. He says that local and international staff rarely meet on some campuses, with the latter “ghettoised” –although he adds that the degree of assimilation may depend on whether the institution is in a large city like Moscow or St Petersburg, or a more isolated location.

Going global: measures of international staff and students and collaboration

Volkov accepts that there are challenges around attracting academics from overseas, with barriers varying according to different disciplines. For instance, recruiting in maths and engineering is expensive because universities want the “best of the best”, to complement the high calibre of the Russian academics they already have, while in the social sciences language is more of an issue.

“At the same time, I am surprised how, in just five years, the best institutions have managed to find good PhD [students] and bring in very promising academics globally,” he says. As an example, he cites the University of Tyumen in Western Siberia, which has attracted several academics from “really excellent institutions” abroad, despite its relatively remote location.

“It is not the whole of Russia [that is attracting academics from abroad] but we have a couple of spots where people from the global market would like to be.”

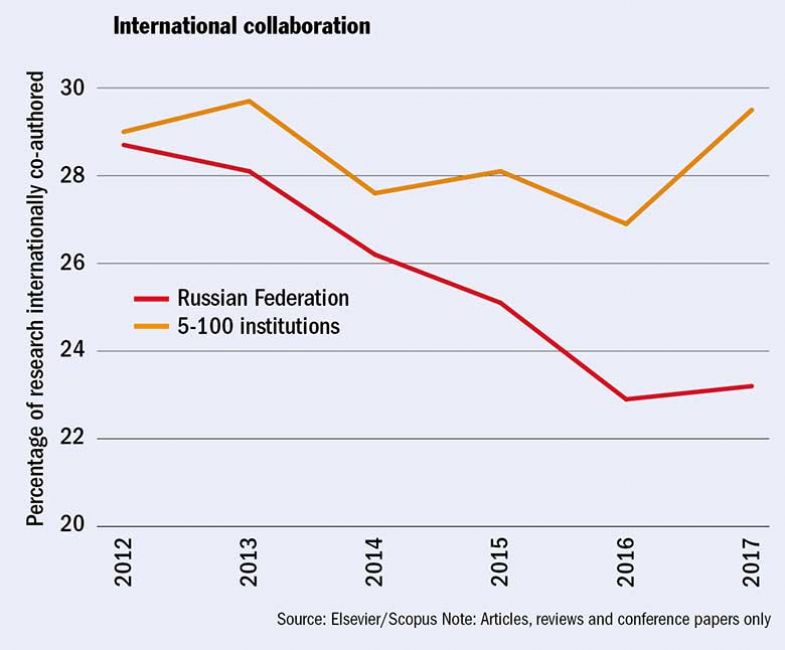

Casting a shadow over all these internationalisation efforts, however, is the dire state of political relations between Russia and the West, and it is an open question whether the 5-100 would have globalised even quicker had things been different. There is certainly evidence that it has hit international collaboration: although the 5-100 institutions themselves have just about managed to hold their own on cross-border collaboration, Russia is virtually the only large research nation in which internationally co-authored papers have fallen as a proportion of total output over the past few years.

Chirikov admits that the political tension doesn’t affect Russian universities’ ability to internationalise “in a positive way”, and concedes that “for some scholars Russia became less attractive as a place to work and as a place for collaboration”. However, he thinks that the weak rouble has actually been the bigger disincentive, and makes the point that Russia’s prominence in global headlines has made it more interesting to scholars as a research topic.

For his part, Volkov believes that the negative political atmosphere has only permeated relations at an institutional level, rather than between individual researchers. But he accepts that it may have been a barrier to greater progress.

“It is not a tension…but [institutions] try to ask more questions [about] each other. It is not healthy, but it is beyond [the control] of the project,” he says.

Not all 5-100 universities are finding international collaboration a problem, however. For instance, almost half of all Scopus-indexed research produced by ITMO University in St Petersburg in 2017 featured international collaboration, up from about a third five years earlier.

The university’s first vice-rector, Daria Kozlova, says that this is down to changing how research teams are organised. She regards as particularly significant the launch of “an open competition for international research labs, which had to have Russian and foreign co-heads. Our top areas of research got a tremendous boost through this process.” The fact that co-heads are not asked to relocate full-time but, instead, to maintain their links with their home institutions means that “the research benefits from true international collaboration”, Kozlova says.

One question raised by all this is the extent to which such programmes and initiatives such as researchers having joint RAS affiliations are, at heart, simply exercises in metric chasing. For his part, Altbach believes that although some of this is going on, he is also sure that the 5-100 universities are “really committed” to improvement for its own sake.

“I would say that all of them – some more successfully than others – are really trying to reform themselves, both because they want to satisfy the metrics and because they do understand that they want to be better and be part of the international academic community,” he says.

The Russian government also seems wary of blatant attempts to game the metrics and has imposed financial penalties on universities found to be using predatory journals to boost publication rates. At the end of the day, Chirikov says, targets always lead to “gaming strategies because every time that you measure quantitatively, [people] try to adapt [their] behaviour to that measurement. Universities are not exceptions.”

Another question is whether there are other reforms that could help Russian universities improve further. Greater autonomy from the government is the one often suggested by all involved: universities, 5-100 leaders and academics that have studied the project.

“Right now, Russian universities have some degree of autonomy but there’s still a lot of input from the ministry…about who we should train,” says ITMO’s Kozlova. “But universities have a much better feel for that. Given more autonomy, the universities [would] be more nimble and effective in training the top experts for the future.”

Chirikov, too, believes that more autonomy “is probably the right direction”, and he points to a decision last year to allow most of the 5-100 universities to grant their own degrees – a major departure for Russia – as a sign that it is happening.

He says that the other major development should be “a fundamental shift from attention on the quantity of academic work to the quality. The scientometric indicators that are used heavily by the ministry and the universities to evaluate themselves need to be complemented with external evaluation…and the basic condition is that it has to be an international evaluation,” Chirikov says.

World rankings data underline that 5-100 institutions are making slower progress on research quality (although their share of research in the top 10 per cent of cited articles is climbing). Their international reputation also continues to lag. Crack both these nuts – which represent two-thirds of the scoring in the rankings – and the 5-100 project may even be in with a chance of ultimately realising the original goal after which it is named.

The Project 5-100 website now states its goal, less precisely, as being to “maximise the competitive position of a group of leading Russian universities in the global research and education market”. And Chirikov points out that the goal of getting five Russian universities into the global top 100 was quickly recalibrated to be applicable to success in individual subject rankings, given the specialist nature of many Russian institutions.

All the hits: a comparison of citation impact

For instance, ITMO, which specialises in information technology and engineering, is now firmly in the top 100 universities in THE’s computer science subject ranking.

Such success, according to Kozlova, is down to Project 5-100’s “ambitious goals and the openness of the selection process, which is carried out in public and involves an international council and foreign experts. We’re a small and dynamic university, and the project has allowed us to undergo dramatic transformation in just about every area: from research to academics to management organisation. We were able to overhaul basically our entire system.”

As for Volkov, having once climbed Everest, he is very familiar with what it takes to undertake steep ascents. For him, 5-100 was never “just a ranking game”. Its purpose was to fundamentally transform the entire Russian system by aiming high. And although the global summit remains a distant prospect, he is in no doubt that progress is being made. So when a decision about the future of the project is taken by the Russian government – possibly next year – it should not only be renewed but expanded, he believes.

“It is about having an excellent education system and making it attractive for global students and global faculty to come to Russia,” he says. “It is a very good goal, a very good idea, and Russian universities should follow this idea and sooner or later…some will be inside the elite group.”

Beyond the 5-100: A Russian provincial university then and now

In Soviet times, the Russian Federation prided itself – not always justifiably – on the excellence and inclusivity of its higher education, especially in the sciences. The 5-100 initiative was both the first real acknowledgement that Russian universities were actually lagging behind international standards, and the first evidence that it was serious about trying to redress that.

But what of those institutions that weren’t selected to take part in that programme? Have they just been left to languish? My September visit to Voronezh State University for its centenary celebrations suggests not.

The 21,000-student institution may be in an agricultural region some 300 miles south of Moscow, but it is well known among British Russianists, around 1,000 of whom have spent a year or a term there as exchange students since 1970. I was there in 1972-73, and this was the first time I had been back to the university.

The early post-Soviet years were not kind to the university. It was desperately short of money, and its reputation as one of the best second-tier universities in Russia suffered. But over the past 10 years it has gained a new lease of life, and is starting to climb up Russian and international rankings.

In Soviet times, Marxism-Leninism, dialectical materialism and political economics were compulsory for all students (except those from “capitalist countries”), and the teaching style and organisation made the whole experience little more than an extension of school. But a slew of new courses and modernised curricula have been introduced, and Voronezh now has sought-after departments of computer science, international relations, journalism and law.

It is also in the process of upgrading its outdated and dilapidated estate. Its main building remains in dire need of renovation, but the public space around it has been beautified with gardens and memorials to past distinguished scholars. The same linoleum flooring, spartan kitchens and communal washrooms and showers still grace the hostels where we lived two or three to a room (a great privilege compared with the four or five Russian students who had to share), but the stultifying, standard-issue regimentation has gone. In our day, no hint of individualism was allowed. Now, doors are customised with names, drawings and photos.

Voronezh’s dynamic rector, Dmitry Endovitsky, is also keen to point out that a splendid new hostel with en-suite rooms has recently been completed – with more to come. Endovitsky deserves a lot of credit for what is happening at Voronezh. An alumnus himself, he has been at the leading edge of post-Soviet higher education and is clearly intent on putting “his” university on the map. Entering university as communism was falling, he opted to study economics and was one of the first Russian graduates to win a studentship under the European Union’s Tempus programme, studying for his master’s in the Republic of Ireland. On his return, he was convinced to stay in academia rather than join the chaotic money-grubbing economy of the 1990s, and became a professor by the age of 30. Voronezh academics elected him their rector in 2010.

What used to be an introverted institution in a city of a million people that was in essence closed to all foreigners but exchange students now looks outward. It has dozens of exchange arrangements with European universities, a tie-in to the Erasmus programme and some foreign industrial partnerships, such as with Siemens. There are visiting professors and fellows from Moscow and foreign universities, and an increasing number of modules are being taught in English. Debate and argument are encouraged.

Voronezh now shares the buzz of a lively Western university – in which its students’ dress, manner and digital accoutrements would make them look perfectly at home. They travel abroad; they speak English without the distinctive Russian accent of yesteryear; they have the same brightness and confidence as their European counterparts. They read many of the same things; they are up with social media.

Voronezh is not alone among Russian universities in seeking greater numbers of exchange places at British and Irish universities – not least because of Russians’ preference for British over American English. But the one hitch in Endovitsky’s internationalisation efforts is that the decline in Russian studies in the UK means that there are far fewer students wanting to go the other way.

Mary Dejevsky is a columnist at the Independent, having previously been a foreign correspondent in Moscow, Paris and Washington.

后记

Print headline: Coming in from the cold