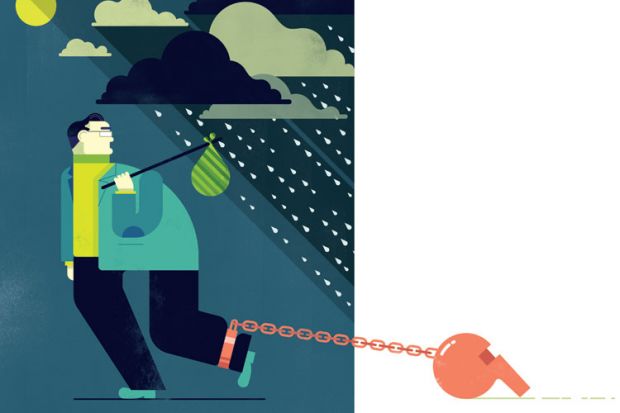

Whistleblowers in universities can hit the national headlines for shining light on issues of public interest, only for their careers to end up in very dark places.

Some of higher education’s most prominent whistleblowers paint a bleak picture about the impact on their subsequent careers. They talk about being persecuted by colleagues after coming forward. But even after leaving their jobs, some believe they still suffer a legacy. One talks about being “effectively blackballed” from ever working again in higher education.

For other whistleblowers, exile is self-enforced. “It has damaged my career. But I’m not really sure I wanted a career by the end of it…There were so many people in prominent leadership positions who behaved so appallingly, I just couldn’t carry on within the profession. I just felt sick about the whole thing,” says Aubrey Blumsohn, who left his post as a senior lecturer in metabolic bone disease at the University of Sheffield, after raising concerns in 2005 about research on a drug made by Procter & Gamble, a funder of research at Sheffield.

But others point to cases where whistleblowers highlight wrongdoing, their concerns are investigated responsibly by universities and their working lives continue as normal.

David Lewis, professor of employment law at Middlesex University and convener of the International Whistleblowing Research Network, argues that the media only report cases “where things go pear-shaped”, as the nature of successful whistleblowing means that it remains within institutions and never emerges in public.

Lewis says that his anecdotal evidence suggests there is “quite a lot of successful whistleblowing that goes on in universities”.

Nevertheless, when things do “go pear-shaped”, the impact on people’s careers can be shattering. Those cases may offer lessons to learn, for both universities and prospective whistleblowers.

Blumsohn says he “can’t claim to have suffered dreadfully” in comparison with some whistleblowers – but he goes on to say that what followed after he came forward was “an attempt to make the rest of my academic work and my job untenable”.

His case began in 2002, when he was working in the research unit led by Richard Eastell, professor of bone metabolism at Sheffield. The unit was researching the effects on patients of Procter & Gamble’s anti-osteoporosis drug Actonel.

Blumsohn raised concerns about abstracts for conference papers submitted by P&G, under his primary authorship, but without the firm having granted him full access to the drug trial data.

His concerns were first raised with senior colleagues and then reported in Times Higher Education in 2005.

The data analysis for the research was carried out by P&G, which paid for the research and which did not release key data to Eastell and Blumsohn. According to Blumsohn, this prevented honest publication of research.

After coming forward, Blumsohn has previously said, his other research work was used as the basis for a series of research grant applications that Eastell sponsored and signed off for a PhD student, without acknowledging Blumsohn’s input and despite his objections.

In 2005, he told the university that he was speaking to the media after losing faith in its internal systems for dealing with such allegations. He was subsequently suspended and told by Sheffield that he could lose his job over alleged “conduct incompatible with the duties of office”, including “briefing journalists” and “distributing information, including a Times Higher article, to third parties with apparent intent to cause embarrassment”.

He later reached a settlement with the university and it dropped all disciplinary charges. However, he left the university in 2006.

Blumsohn says of what happened afterwards: “I withdrew from medicine completely, I withdrew from academia and ultimately withdrew my medical registration as well.”

Given the impact on his career, does Blumsohn regret coming forward with his concerns? “I had to do that,” he says. “As a scientist, I couldn’t just go along with having my name attached to manipulated publications, based on secret data ghost-analysed by pharmaceutical companies.”

Could Sheffield have dealt with his concerns more effectively? “I don’t know how Sheffield could have done better, or indeed how any medical school could have done,” Blumsohn replies.

He clarifies: “The problem these days is that some parts of universities – most notably medical schools but some other parts as well – have so many conflicts of interest and financial imperatives guiding what they do, I’m not sure other universities would necessarily have behaved differently from Sheffield. When millions of pounds are at stake both in private fees for academics and university funding, and a pharmaceutical company is wanting you to dance, the pressure to go along and to get staff to remain quiet is overwhelming.”

Asked about the university’s whistleblowing procedures and any lessons learned, a Sheffield spokeswoman says: “We know that one of the hallmarks of a good employer is building an open and supportive culture where staff feel they can raise issues of any kind. That’s why we are proud of our recent staff survey results which show this is exactly what type of organisation we are.

“We fully support world-leading researchers in their pursuit of academic excellence and we’re determined to provide them with the necessary assistance should they encounter any concerns during their research.”

Blumsohn was a member of the Association of University Teachers, which later merged with a further education union to become the University and College Union. He describes the central UCU as being “completely useless” when it comes to “issues of scientific integrity, academic bullying or fundamental issues of academic freedom”, accusing it of treating cases “as if they are primarily legal, employment disputes, while completely ignoring huge issues of principle”.

Blumsohn raises similar objections about the Public Interest Disclosure procedure (see ‘Speaking out: protected disclosures’ box, below). “It is based on the erroneous premise that the ultimate and only goal of whistleblower protection is to achieve a winnable employment tribunal [case],” he says.

He never framed his concerns as a public interest disclosure. He argues that the real goal of whistleblowing is “to correct wrongs and bring system failures into the public domain almost regardless of the consequences – and that is precisely what legislation and groups supporting whistleblowers should aim to achieve”. Current legislation “prescribes that you need to spend innumerable years going through internal procedures, and then to obfuscatory prescribed external bodies”, he laments, and “all you would be left with is the remote possibility of a successful employment tribunal [case]”.

Paul Buckland’s case began when he marked a set of undergraduate archaeology exam papers in 2006. Then a professor of environmental archaeology at Bournemouth University, he and a second marker both “agreed that the quality was abysmal”, failing 18 out of 60 papers.

The papers then went to “another individual who had no real knowledge of the subject and he passed them”, says Buckland. Complaints to his managers, including a pro vice-chancellor, “got nowhere”, he continues.

“Eventually I was in the position that I could either accept the fact they could arbitrarily remark my papers, or I had to resign. Since this was a serious attack on my integrity, I had no option but to resign.”

Buckland saw himself as defending “students who worked hard for their degrees, who were being short-changed by a system where basically, if you could afford it, you got a degree”.

He later won a tribunal case for constructive dismissal, which the university overturned on appeal – only for the Court of Appeal to ultimately uphold his claim in 2010.

Since then, he says he has applied for 19 university posts at all levels without a single interview, despite what he calls a “pretty good publication record”.

Nick Petford, a pro vice-chancellor at Bournemouth at the time and now vice-chancellor of the University of Northampton, wrote a letter that was published in THE in 2010. This letter claimed that Buckland “failed to adhere to our marking procedures and protocols; that he refused to cooperate with an internal academic inquiry into the matter; and that, crucially, his marking was not supported by three independent external examiners, all experts in their field”.

Buckland rejects those claims. And he says that Petford’s letter “effectively blackballed” him from work in higher education and “killed any job prospects”.

Higher education in the UK is quite small. Everyone is networked…which allows rumours to be disseminated within senior management teams

Does he believe any changes could be made in universities to avoid more cases like his? “I think it’s the fate of anyone who steps out of line,” Buckland answers. Students are now seen as “paying customers”, he says, to explain universities’ attitudes to concerns about academic standards. “They are no longer students. They are buying a product.”

Buckland says the UCU did “an extremely good job” in defending him. But at the time the Quality Assurance Agency, with which he attempted to raise concerns, was “hopeless” as it was “part of the old-boy network”, he claims. (The QAA introduced new procedures for raising concerns in 2007 – see ‘Escalating issues: taking the QAA route’ box, below.)

Buckland describes himself as “extremely bitter to see the bosses…promoted” and “very sad” that in his view he caused those who supported him to lose their jobs.

Bournemouth declined an invitation to discuss any lessons learned from the incident or its whistleblowing policy more generally.

Between 2000 and 2003, Harinder Bahra was associate dean for external development at Southampton Institute, now Southampton Solent University.

In 2002, he raised concerns around discriminatory practices and the management of Higher Education Funding Council for England funds. After coming forward, he eventually made a race discrimination complaint and resigned in 2003.

He found a new job as director of marketing at Brunel University, only for things to go wrong when his new employer found out about his outstanding employment tribunal against Southampton Institute. Four months after starting at Brunel, he was sacked on the grounds that he had not passed his probationary period.

Bahra then took Brunel to another employment tribunal. It ruled that he had “suffered unlawful race discrimination by way of victimisation”. Bahra won an undisclosed sum in an out-of-court settlement and the university offered him an apology.

Southampton Institute was in negotiation with Bahra about a settlement while he was at Brunel. At that time, Southampton Institute decided to “water down” its originally favourable reference for Bahra, the tribunal in the Brunel case found.

“The tribunal did not accept that there had been no discussions between the senior people at the Southampton Institute and at Brunel University. Plainly there had been,” the judgment says.

Southampton Institute eventually settled with Bahra and issued a public statement, which said it would be “bringing forward the review of its policies and procedures relating to equal opportunities to help to encourage and promote an environment of diversity”. It also thanked Bahra for his “positive contribution” to the university.

Southampton Solent University declined an invitation to comment on any lessons learned from the case, or on its whistleblowing procedures more generally.

Bahra has not had a full-time role in higher education since leaving Brunel, although he has held temporary positions. He now runs his own consulting firm.

“There seems to be an underlying assumption that life will return to normal if you’ve been exonerated and received an unreserved apology. It doesn’t. One continues to pay a long-term penalty for raising issues and concerns and many employers will view you as high risk,” he says.

Asked if what happened at Southampton and Brunel is the reason he has not found a full-time job in higher education, he calls those events “a contributing factor. If you do a Google search on me, one of the top items that comes up is ‘Brunel settles after race row’. With many recruiters using social media, anything detrimental is likely to reduce the employment prospects for whistleblowers.”

He continues: “Certainly when other [higher education whistleblowers] have contacted me they have said that their treatment and employment trajectory follows a similar pattern. After raising the issues or concerns they can be subject to spurious allegations, identified for redundancy or dismissed. Once out, many cannot get back in: they are not shortlisted, or they’ve been shortlisted but never been appointed. It could be that I and others are just poor applicants. But it could also be that there is something else, something a bit more sinister that is happening here.”

Bahra adds: “Higher education within the UK is quite small. And of course, everybody is formally and informally networked…which allows rumours to be disseminated within senior management teams.”

Would he do the same again, knowing the subsequent impact on his career? “I think that it would be a dereliction of duty not to come forward if one is a senior manager and sees any wrongdoing,” he replies. “Sometimes you have to come forward because it’s the right thing to do. Is that not what ethical leadership is about?”

Bahra makes a positive case for authentic whistleblowing. “Whistleblowers are part of the renewal process within organisations,” he says. “You have to have people who are not suffering from groupthink and who can provide an alternative view challenging poor practices within organisations. You shouldn’t effectively be penalised for doing what is the right thing.”

He adds: “I think universities need to embrace [whistleblowing]. That’s what academic freedom is about, isn’t it? The ability to put forward a view…Organisations shouldn’t become defensive and turn on the individual. What they should do is have a proper due process…and investigate matters diligently and appropriately.”

If some universities have been “defensive” over whistleblowers, is that entirely their fault? Or is it also that legislation has failed to create the culture shift needed?

Middlesex’s Lewis says: “The legislation doesn’t give a right to whistleblow; it doesn’t say you have a right not to be victimised. It says if you are victimised, you may bring a claim against your employer.

“I actually believe that if you can prove an employer has victimised you because you made a protected disclosure… that should be a criminal offence.”

That is the case in Australia, Lewis explains, which also grants whistleblowers absolute and qualified privilege in defamation cases, in effect protecting them from being sued for libel, “our law says nothing about that”.

Research led by Lewis, published by Middlesex, has found that two-thirds of UK universities are using out-of-date whistleblowing procedures that fail to reflect 2013 amendments to legislation extending legal protection (see ‘Speaking out: protected disclosures’ box, below).

At 111 universities out of 143 (78 per cent), procedures stated that those who report a concern must be acting in good faith to qualify for protection, Lewis’ research found. But the 2013 changes scrapped the “good faith” requirement, extending protection under legislation to those who act in “bad faith” – for example, out of personal spite or revenge.

Hefce’s policy also seems to be out of date on this issue. “We welcome [whistleblowing] allegations insofar as they are brought to our attention in good faith and relate to our statutory functions,” says the Hefce website.

The Concordat to Support Research Integrity, published by Universities UK in 2012 with a range of signatories including the funding councils and Research Councils UK, addresses whistleblowing.

It says that universities and other research bodies should have “clear, well-articulated and confidential mechanisms for reporting allegations of research misconduct” and should “act with no detriment to whistleblowers making allegations of misconduct in good faith”.

But the sector has no guidelines for how to deal with whistleblowing beyond research.

All of which leaves a question hanging: if you work in a university and you suspected wrongdoing, what would you do next?

Speaking out: protected disclosures

“Whistleblowing is when a worker reports suspected wrongdoing at work. Officially this is called ‘making a disclosure in the public interest’,” explains the UK government’s website.

This refers to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998, which inserted provisions into the Employment Rights Act 1996. The legislation means that if workers can prove they have been sacked for whistleblowing, they will win a claim of unfair dismissal at an employment tribunal.

In terms of what kind of whistleblowing is protected, the legislation cites disclosures about criminal offences; about people failing to comply with legal obligations; about miscarriages of justice; about the health and safety “of any individual” being endangered; about the environment being damaged; or about cover-ups of any such matters.

Under the legislation, whistleblowers can make disclosures not just to their employers but to appropriate regulatory bodies. The Higher Education Funding Council for England, for example, makes information on its public interest disclosure procedures available on its website.

Following revelations that those speaking out against wrongdoing at Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust had been victimised and harassed for doing so, the government amended the legislation in 2013 in the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act.

Employers can now be held “vicariously liable” for any “detriment” suffered by whistleblowers at the hands of other staff.

In addition, the amended legislation extended whistleblower protection to those who make disclosures in bad faith, for example with the motivations of financial gain or spite.

The 2013 amendment replaced the “good faith” requirement with a requirement that whistleblowers must have a “reasonable belief” that they are acting “in the public interest”, in order to qualify for protection.

David Lewis, professor of employment law at Middlesex University and convener of the International Whistleblowing Research Network, says that, rather than automatically classing revelations about wrongdoing as public interest disclosures, universities will also have processes for equal opportunities or bullying and harassment, or grievance procedures, which they may use to field concerns.

“Under the legislation, you have to decide inside a university which procedure you are going to invoke,” Lewis says. He adds that it would be “smart” for whistleblowers to cite the Employment Rights Act, given the protection it offers.

For Lewis, the 2013 changes and the public interest test are “far less significant than requiring those who have been victimised to actually have a deposit fee and a hearing fee” for tribunals. Fees of up to £250 to lodge a tribunal claim were introduced by the coalition government in 2013, with further fees as cases progress. This creates “a major problem” of “access to justice”, Lewis claims.

Escalating issues: taking the QAA route

One option for academics uneasy about standards is to use the Quality Assurance Agency’s “concerns” process.

Under the scheme, the agency can “investigate concerns about academic standards and quality and about information that higher education providers make available about their provision, where we think such concerns indicate serious systemic or procedural problems”, the QAA says.

Although it is unlikely to field many complaints about the type of serious wrongdoing classed as “whistleblowing”, it is nevertheless a mechanism specific to higher education for airing concerns.

According to figures supplied by the QAA, of 105 complaints received last year, just two led to a full inquiry: one into the PhD examination process at the University of Bedfordshire; and one into a collaborative agreement between the University of Gloucestershire and the private Williams College.

The scheme was launched in 2007 and revised in 2010 after a cross-party group of MPs from the Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee argued that the sector would benefit from “an independent arbitration and adjudication service” for reviewing academics’ concerns about standards in a report published in 2009. Those raising concerns can “tick a box” to opt for anonymity, explains Stephen Jackson, director of quality assurance at the QAA.

Of the 105 concerns received last year, 46 “did not qualify for an initial inquiry”, says the QAA. Of the remaining 59, 10 were “resolved by the provider acknowledging the weaknesses identified and agreeing actions to address them”. Three were “resolved by the provider demonstrating they were already aware of the issues and were taking appropriate action”.

Two “led to a full investigation” and one “was referred to a forthcoming QAA review”.

Another 16 were “disproved by the provider demonstrating that the concerns were not systemic or procedural but were isolated mistakes (four resulted in action to resolve an individual issue)”, the QAA says. Three “related to partnership agreements that had since terminated”; one “related to a provider that was no longer an institution we could investigate”; and 23 are “ongoing”.

The IUSS committee’s 2009 report, Students and Universities, also called for legislation to strengthen protections for those raising concerns about academic standards in the 1988 Education Reform Act.

“It appears that the current protections within the sector and the internal arrangements of some higher education institutions may not provide sufficient protection to whistleblowers raising, in good faith, potentially serious concerns about standards at higher education institutions,” the report says. “The pressures within the system to protect the reputation of the institution are so strong that they risk not only sweeping problems under the mat but isolating and ostracising unjustly those raising legitimate concerns.”

The MPs were particularly concerned by Manchester Metropolitan University’s handling of a case in which a member of staff raised concerns about alleged dumbing down.

Walter Cairns was removed from the university’s academic board after making a submission of written evidence to a parliamentary inquiry about a course he taught at Manchester Met in which marks were raised unilaterally following an 85 per cent failure rate.