Click to download and view the full results

As a grocer’s daughter who rose to become Britain’s first female prime minister, she stands as an example to our daughters that there is no glass ceiling that can’t be shattered.”

Barack Obama’s eloquent tribute to the late Baroness Thatcher may have struck a hopeful note, but sadly the glass ceiling remains frustratingly unbroken in academia and elsewhere.

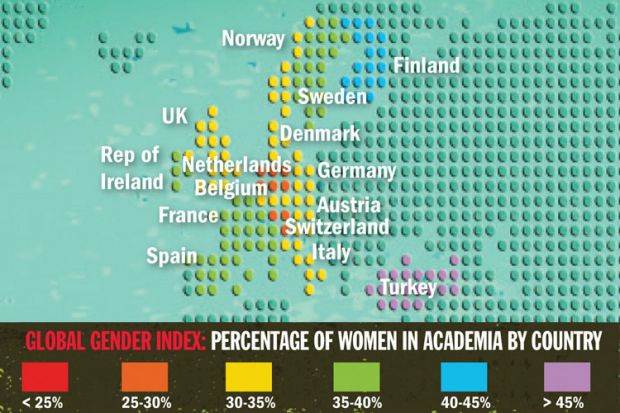

An analysis by Thomson Reuters in association with Times Higher Education shows startling levels of gender inequality in research-intensive universities across the world. The gap persists not just in emerging nations but also in some of the world’s most highly developed countries - where the fight for women’s rights and equality has gone on for decades.

Thomson Reuters collated data provided voluntarily by institutions ranked in the top 400 of THE’s World University Rankings to produce our Global Gender Index. The results highlight a glaring disparity in the ratio of male to female academics in nearly all of the countries assessed.

The widest gender gap is found in Japan, where women make up just 12.7 per cent of the academics at the country’s top-rated universities. It is followed by Taiwan, where only 21.3 per cent of faculty at the nation’s top seven universities are female.

The UK, which has 48 institutions in the survey, fares slightly better, with women making up 34.6 per cent of academic personnel. It is just behind the US, where the figure is 35.9 per cent among 111 representatives.

The problem persists even in Scandinavian countries (often regarded as among the most progressive in the world), such as Sweden (36.7 per cent), Norway (31.7 per cent) and Denmark (31 per cent).

One country, however, comes close to achieving an equal gender split. In Turkey, 47.5 per cent of staff at the top five universities are female.

“Academia is characterised as being cutting-edge, innovative and hypermodern, yet wherever you look it is underpinned by the archaism of male domination,” says Louise Morley, director of the Centre for Higher Education and Equity Research at the University of Sussex. “Why are so many women missing from leading institutions, particularly at senior management levels?”

One reason, she believes, is that the entrenched patriarchal power nexus at universities, with their male-dominated departments, interview boards and academic journal editors, is self-perpetuating. This makes it more difficult for women to attain the critical acclaim and academic capital that might lead to full-time positions, or sabbaticals to further their work.

“There is a cultural climate that favours men,” Morley contends. “Women are not recognised for their talents or abilities and are often forced to do low-level, high-volume administrative work, while many more men assume external-facing roles that have immediate…career gains.”

Another issue is that female academics are often less able to make vital overseas links because they have greater family and personal commitments that can prevent international travel, argues Bahiyah Abdul Hamid, deputy director of the Women’s Leadership Centre at Kebangsaan University in Malaysia.

This can have serious consequences, thwarting their research potential and career prospects at leading universities, she argues.

“Men can achieve higher citations than women partly because they can network internationally,” says Hamid.

Building such contacts is becoming increasingly important to career progression: she cites research showing that journal papers are more likely to be rated highly when they are the result of international collaboration.

Does sexism play a large role in reinforcing academic gender inequality?

Traditional Japanese attitudes towards women in the workplace are one key reason why the country is bottom in our Global Gender Index, insists Susan Burton, associate professor at the Faculty of Foreign Languages at Bunkyo Gakuin University in Tokyo.

“These statistics are not at all surprising,” she says. “They represent the continuing belief in biological determinism within Japanese society - that men are more suited to the public sphere while a woman’s ‘eternal employment’ (eikyu shushoku) is to raise children and keep house.

“Such views are maintained by the old men in politics, such as former prime minister Yoshiro Mori, who has openly stated that women who don’t give birth should not be eligible for the state pension and that the falling birth rate is caused by the ‘over- education of women’.”

Female students are directed towards two-year “tandai” colleges, where subjects include “tea-making and applying make-up”, or so-called “soft” arts-based subjects that will not scare off potential husbands, she adds.

“Male peers participate fully in academic life, but female educators are still expected to marry and raise children,” Burton says. “The result is that they often find themselves in part-time jobs with no promotion prospects, no time to write or publish, and unable to attend conferences.”

As is Japanese custom, full-time employees are expected to work long hours and weekends.

“This makes things very difficult for my female colleagues who tend to go silent in faculty meetings after 5 o’clock in the hope that they will finish in time for them to pick up their children,” says Burton. “One of my colleagues considered refusing a promotion because she felt her husband would be angry with her for being away from the home too much.”

Masako Egawa, executive vice-president of the University of Tokyo, one of the few high-ranking women in the country’s academy, says: “The low ratio of women among students and staff…reflects Japanese society at large, where women play very limited roles; Japan ranked 101st in the Gender Gap Report 2012 by the World Economic Forum.

“At Tokyo, women have accounted for less than 20 per cent of incoming undergraduate students for the past 10 years. This is because fewer women apply to our university (they account for less than 20 per cent of the applicant pool).”

Egawa says that the institution is working hard to enhance applicant diversity: it wants the proportion of women to increase to 30 per cent by 2020. In 2012-13 the figure was 18.8 per cent, a 1.5 percentage-point rise.

So what lessons could Japan and other countries learn from Turkey, which heads our gender equality list? Gülsün Sağlamer, former rector of Istanbul Technical University, says that a mix of historical and cultural reasons explains why female academics have prospered in Turkey’s universities, but stresses that continuing support is vital.

She highlights how the crumbling Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century acceded to many of the demands of the women’s liberation movement, while the republic established in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s first president, guaranteed women equal rights to higher education, as well as the opportunity to join the Civil Service.

“The new universities that opened in the republican era made special effort to enrol female students,” Sağlamer says. “Some have argued that women served as kind of a reserve army in the Ataturk era.”

The scarcity of high-status men after the First World War’s bloodshed meant that class overtook gender and women were called to duty, she adds.

Later generations of Turkish women “remembered the efforts of the newly built republic in this endeavour with gratitude and pride, were socialised to believe that women were not inferior to men and could be successful in any field they chose to study”.

Turkey’s extended-family tradition also helps female academics, allowing them to return to the workplace quickly after having children, Sağlamer explains.

“Many universities also provide nurseries and primary and secondary schools on their campuses, together with on-campus housing, which makes life easier, while flexible working hours help women academics to organise themselves for their careers.”

Official figures suggest that a glaringly wide gender gap still exists at senior levels, however. According to data presented at a recent British Council workshop, Absent Talent: Women in Academic and Research Leadership in East Asia, just 7 per cent of Turkey’s vice-chancellors are women. The situation is worse in Japan, where only two of its 86 public universities (2.3 per cent) are headed by women (one leading an all-female institution).

This gap is less wide in Australia, where 18 per cent of higher education institutions are led by women. In the UK the figure is 14 per cent, but only one of the 24 large research-intensive institutions that make up the Russell Group - the University of Manchester - is female-led.

Our data also shed light on the gender imbalance within different academic subjects.

Overall, the student body is balanced: 50.3 per cent of students at the top 400 institutions are women. However, they make up just 33.7 per cent of staff and the proportion is far lower in some disciplines.

While 43 per cent of academics in the arts and humanities and 38.5 per cent in the social sciences are female, the proportion falls to 19 per cent in the physical sciences and just 15.6 per cent in engineering and technology.

The figures in our global survey broadly correspond with the findings of a recent European Commission report, She Figures 2012: Gender in Research and Innovation. Its analysis of European countries shows that female PhD graduates equal or outnumber men in all fields of study except for science, mathematics and computing (40 per cent), and engineering, manufacturing and construction (26 per cent).

However, it adds that women’s academic careers remain “markedly characterised by strong vertical segregation”: while women make up the majority of students (55 per cent) and graduates (59 per cent), this numerical dominance is lost if they move into academia.

“Women represented only 44 per cent of grade C academic staff, 37 per cent of grade B…and 20 per cent of grade A”, the most senior positions, the report says.

In science and engineering, the proportion stands at 32 per cent of grade C, 23 per cent of grade B and only 11 per cent of grade A personnel.

Meanwhile, just 7.9 per cent of engineering and technology professors are women, although in the humanities and social sciences the figures are 28.4 and 19.4 per cent, respectively.

The report finds little sign of improvement.

“There is no evidence of spontaneous reduction of gender inequality over time. Policies…are needed to ensure that constant progress is made towards gender-equality in research and scientific careers,” it concludes.

The lack of women in senior roles is something that the recent British Council-backed report Manifesto for Change - written by Morley - hopes to change. In it, she calls for university rankings to reflect institutional efforts to promote gender equality in staffing.

“These figures should be weighted in future rankings to reflect the progressiveness in gender equality being achieved,” argues Mana Nakagawa, a PhD candidate at Stanford University’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. “Women are making visible headway in attaining higher proportions of…degrees, but they are still underrepresented in the higher echelons of university positions…and there are stark differences across fields of study.”

Times Higher Education will be exploring the issues raised in this feature in a series of articles in the coming months.

Global gender index: methodology

The analysis is derived from data collected for the 2012-13 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

Individual universities provided Thomson Reuters with the information voluntarily as part of the Thomson Reuters Institutional Profiles project.

For statistical validity, only countries with four or more institutions in the top 400 universities are included. Of these, 368 reported gender information (92 per cent). This drops to 75 per cent for the subject-based analysis.

Data are based on the year 2010 or the academic year ending in 2010, and show all staff employed in academic posts (such as lecturer, reader, associate professor or professor). They include permanent staff and those employed on long-term contracts.

The figures do not include non-teaching fellows (as the term varies across countries), those only doing research, postdoctoral researchers, research assistants, clinicians of all types (unless they hold academic posts) and technicians.

South Korea is excluded because only three institutions reported data on gender and two were institutions of technology.