Fengjia night market in Taichung is one of the largest of its kind in Taiwan. From 6pm until midnight, teeming crowds compete with motorbikes in streets overflowing with stalls that sell everything from deep-fried octopus to the latest mobile phones.

It is a young crowd, and many are university students. In fact, Taichung – Taiwan’s second most populous city after the capital, Taipei – contains 10 distinct universities. Nor is this unusual: the country as a whole has about 130 higher education institutions if you include those in the state and private sectors. Add junior colleges and institutes of science and technology (some of which include the word “university” in their titles) and the number jumps to more than 150. In 1950, there were just seven.

That presents young Taiwanese with a choice of university every bit as wide as Fengjia’s range of xiaochi (hot snacks). But while marketgoers may have to elbow each other aside to get to their favourite fried milk stand, higher education is very much a buyer’s market. According to the CIA World Factbook, Taiwan’s fertility rate of just 1.12 children per couple put it 156th out of 158 listed countries in 2016, with only Macao and Singapore ranked lower.

The implications for universities are clear. A report by the Taiwan Ministry of Education last year found that 151 tertiary institutions had offered classes that had seen zero people enrol. Sixty-four of the affected departments and graduate programmes were at the more respected public universities, with the remaining 87 at private schools. A further 269 programmes across the sector were less than 30 per cent full, the ministry’s report found.

Even the country’s most prestigious university, the National Taiwan University in Taipei, was not immune. Seven doctoral programmes – including anthropology, drama and theatre, art history, sociology, and translational medicine – failed to recruit a single student.

The government of Taiwan is taking the issue very seriously. Universities that do not achieve overall enrolment rates of 80 per cent or more for two consecutive years are to have the number of students that they are permitted to admit reduced, while those whose enrolment rates are between 60 and 80 per cent will also be officially monitored and offered guidance.

Ageing populations are common in many East Asian countries. Joining Taiwan, Macao and Singapore in the bottom 20 countries for birth rate are South Korea, Hong Kong and Japan – all three of which also have huge university sectors. So the way in which Taiwan’s universities handle the issue could provide several pointers to those elsewhere in the region.

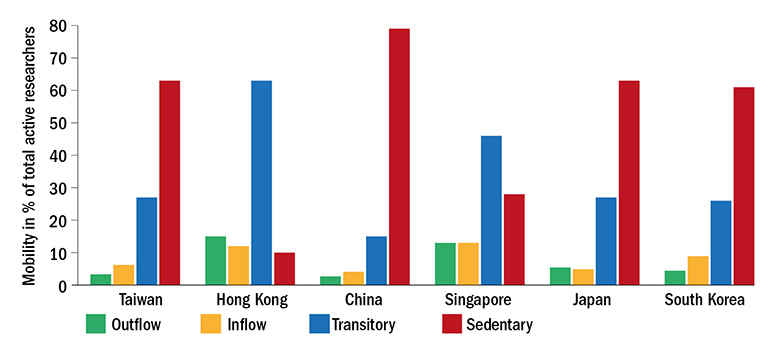

Researcher mobility

Note: Results draw on Scopus data, 1996-2014. Outflow = researchers who first published with an affiliation in country X and have subsequently migrated from country X to another country (or countries) for at least two years without returning to country X – or – researchers who migrated to country X from another country, stayed for at least two years, and then once again migrated to another country for at least two years without returning to country X. Inflow = researchers who first published in a different country and subsequently migrated to country X, staying for at least two years – or – researchers who first published in country X, migrated to another country for at least two years, and then returned to country X for at least two years. Transitory = researchers who have mainly published with affiliations in country X and spent less than two years abroad before returning to country X – or – researchers who published mainly with an affiliation in a country (or countries) other than country X, and have spent less than two years in country X before migrating to another country. Sedentary = researchers whose Scopus author data indicates they have not published with affiliations outside country X. Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool

"The Confucian emphasis on education, and intellectuals’ special role in society have permeated Taiwan’s approach to higher education,” says Vincent Wei-cheng Wang, dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences and professor of politics at Ithaca College, New York. “Culturally, parents want their children to go to [university], and often view a college diploma as essential to a life of success.”

The statistics back this up. Taiwan has one of the most highly educated populations in the world when defined by the percentage of adults with a college degree. For Taiwan, that figure is 39 per cent, compared with an average of 30 per cent among members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Indeed, Taiwan’s constitution mandates that no less than 15 per cent of the total national budget should be devoted to educational expenditure, Wang explains – although critics say that not enough of this money goes to universities.

“In the early 1990s, partially as a result of democratisation, Taiwan’s higher education sector went through a populist change,” Wang continues. “Many new universities came on the scene as a result of upgrading existing polytechnic, normal and professional colleges. Although higher education became more democratic – accessible to more families – the total national budget [for it] did not fundamentally change from the old formula.” The result is that, according to Ministry of Education figures, spending per student fell from NT$200,000 (£5,120) in 1980 to NT$130,000 in 2014.

Speaking at the THE Research Excellence Summit in Taichung earlier this year, Wen-Hwa Lee, chancellor of the city’s China Medical University, pulled no punches in outlining the many issues that he believes are hampering the development of Taiwan’s universities.

He lamented the country’s overly bureaucratic education system, with too many regulations and restrictions; low levels of investment in education; low tuition fees; low government grant levels; low donations; few renowned scholars; a limited talent pool; and a lack of high-quality infrastructure.

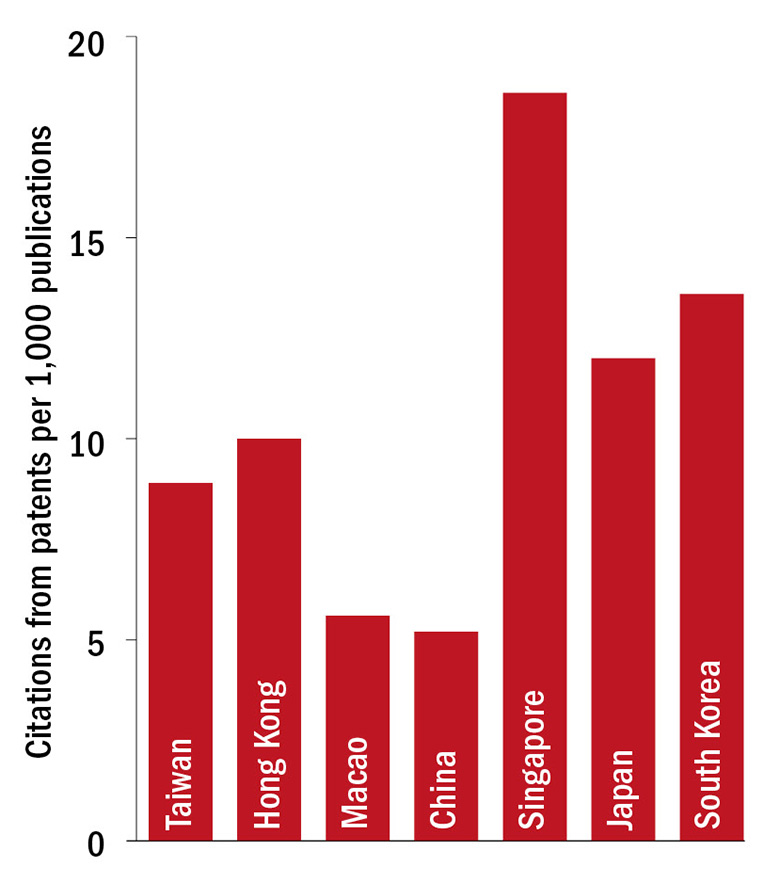

Industry links

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool

Tellingly, institutions that remain in demand are unable to increase their student numbers, or charge higher fees. This means that “limited financial resources are the biggest challenge for most universities in Taiwan”, according to Shia-Chun Chen, vice-president and chair professor of mechanical engineering at Chung Yuan Christian University in Taoyuan City. Tuition fees at the five top-ranked universities in Taiwan range from NT$45,000 to NT$79,000 (£1,100 to £2,000) per year.

Ministers have made some attempts to address the issue. A programme known as the “Road to Top Universities Project” promised NT$50 billion in funding between 2011 and 2016 to support Taiwanese universities’ research facilities and to develop their international reputations. However, the investment did not result in immediate gains in international rankings and, by 2015, the Ministry of Education had deemed the project a failure. That is perhaps borne out by the 2018 THE World University Rankings. Taiwan only just managed to break the top 200 after the National Taiwan University in Taipei fell three places to joint 198th. Its second-highest institution, National Tsing Hua University, fell from the 251-300 band to the 301-350 cohort.

The ministry’s immediate priority appears to be the demographic issue. According to deputy education minister Yao Leehter, the number of prospective undergraduates could plummet to just 723,000 over the next 10 years or so. This would represent a decline of more than 410,000 compared with 2013 – and Leehter has reportedly said that some institutions will need “an exit plan”.

Bi-Yu Chang, deputy director of the Centre of Taiwan Studies at Soas, University of London, says that it is almost inevitable that “quite a lot” of newer universities “are going to close down”. “Taiwan just can’t sustain these universities, which were set up by anyone who had enough money. There simply won’t be enough students.”

Many mergers have already begun to happen. In July, it was announced that three institutions in the Kaohsiung municipality would combine to become the National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology. And, last year, the National Chengchi University announced that it would merge with the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology. According to government estimates, between eight and 12 of Taiwan’s 51 public institutions and 20 to 40 of its private universities could be merged or closed by 2023.

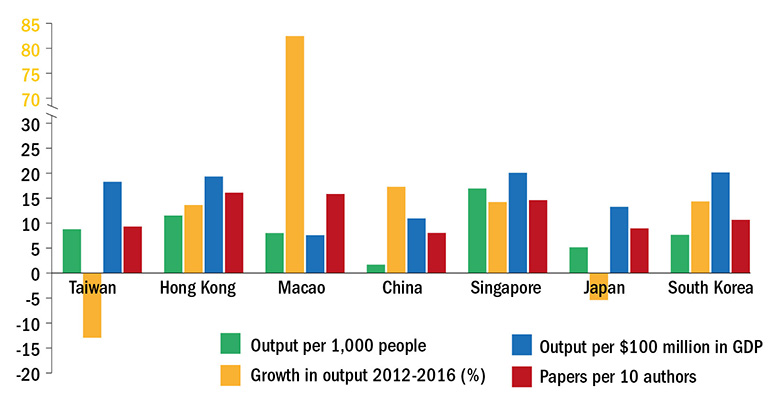

Research productivity

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool. Year range: 2012-2016.

For those institutions that remain, attracting students from China could become critical. Although relations with the mainland are currently more strained than they have been for years after new Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen refused to acknowledge Beijing policy that views Taiwan as part of “one China”, the growing population of wealthy Mandarin-speaking youngsters in the People’s Republic could offer a financial lifeline to struggling Taiwanese universities.

But why would Chinese students want to make the journey across the Formosa Strait?

“[Taiwan’s status as] the last outpost of the old Republic of China is attractive to students from the mainland curious to make comparisons with their lives back home,” says Dafydd Fell, an expert on Taiwanese politics and director of the Centre of Taiwan Studies at Soas.

Chang adds that some Chinese see Taiwan as a cultural sanctuary: “When I talk to mainland Chinese students in Taiwan, the reason that most of them came was because they have been taught that Taiwan is the last haven for traditional Chinese culture. That’s how they view Taiwan,” she says.

But the desperation to attract fee-paying students from mainland China is, many believe, having a damaging impact on Taiwanese academic freedom. Earlier this year, for instance, a Ministry of Education emergency investigation reported that at least 80 institutions in Taiwan had signed agreements with institutions in mainland China saying they would avoid teaching topics that China may view as controversial – such as the “one China” policy, or the issue of Taiwanese independence.

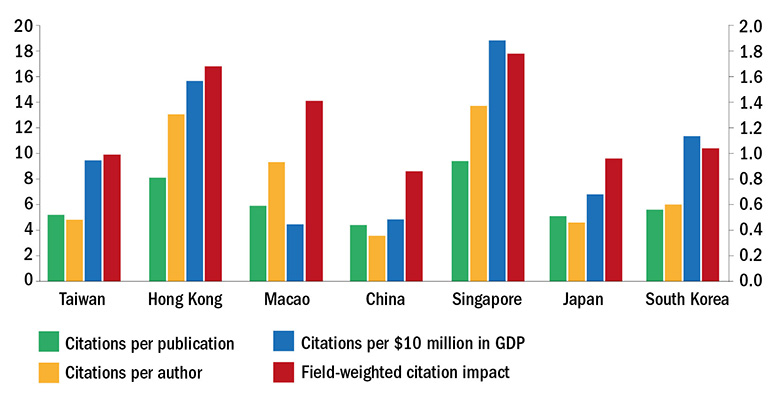

Research quality

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool. Year range: 2012-2016. Note: Field-weighted citation impact should be read on the right-hand scale.

Fan Yun, a sociology professor at the National Taiwan University, led the campaign against the practice of institutions suppressing controversial topics in order to keep relations with China sweet. She started a petition against the restrictions in teaching, saying that she felt “ashamed and heartbroken” by the news.

“In a university classroom, what one teaches and refrains from teaching are both political actions,” she said at the time. “If humanities education is obliged to negate Taiwanese independence in discussions about Taiwan’s future, we have no such thing as academic freedom in universities.”

In response, the ministry claimed that it had prohibited universities from signing any such agreements.

“I don’t have any prejudice against students from China,” Yun tells THE. “I have taken them as my advisees in the past and learned a lot from them. However, it is an issue of academic integrity, which I think our universities should stand for.”

She remains concerned that although the Taiwanese government claims to have acted, such practices could still occur. If they do, she hopes that “all the global intellectuals…will not hesitate to stand up against censorship from China”.

Another recent source of embarrassment for Taiwan was 2014’s scandal over fake peer review, when a computer science researcher at National Pingtung University of Education, Peter Chen, was exposed by the publisher Sage as having been at the centre of a “peer review and citation ring”. Some of the 60 papers retracted as a result had been co-written by Taiwanese then minister for education, Chiang Wei-ling. Although he claimed to have no knowledge of Chen’s activities, he nevertheless resigned from the ministry.

Largely as a result of Chen’s activities, Taiwan is second only to China in terms of the total number of papers retracted as a result of fake peer review in recent years, according to the Retraction Watch website. The pressure to publish in Taiwan – as in many countries – is intense and, according to Ithaca College’s Wang, was probably ramped up further by the government’s Top Universities project, which placed institutions in competition with each other for funds.

“This…arguably incentivised and pressured faculty to publish in peer-reviewed or indexed journals, [which] might have contributed to some researchers cutting corners or committing fraud to get published,” he says. Soas’ Chang, meanwhile, describes Taiwan’s universities as “too rigid” about how many journal articles researchers are expected to publish.

The peer review scandals have forced the government to act. In March, the Ministry of Science and Technology announced plans to establish an Office of Research Integrity, based on the US body of the same name. The office will create a database of ethical breaches, which will serve as a reference for case reviews.

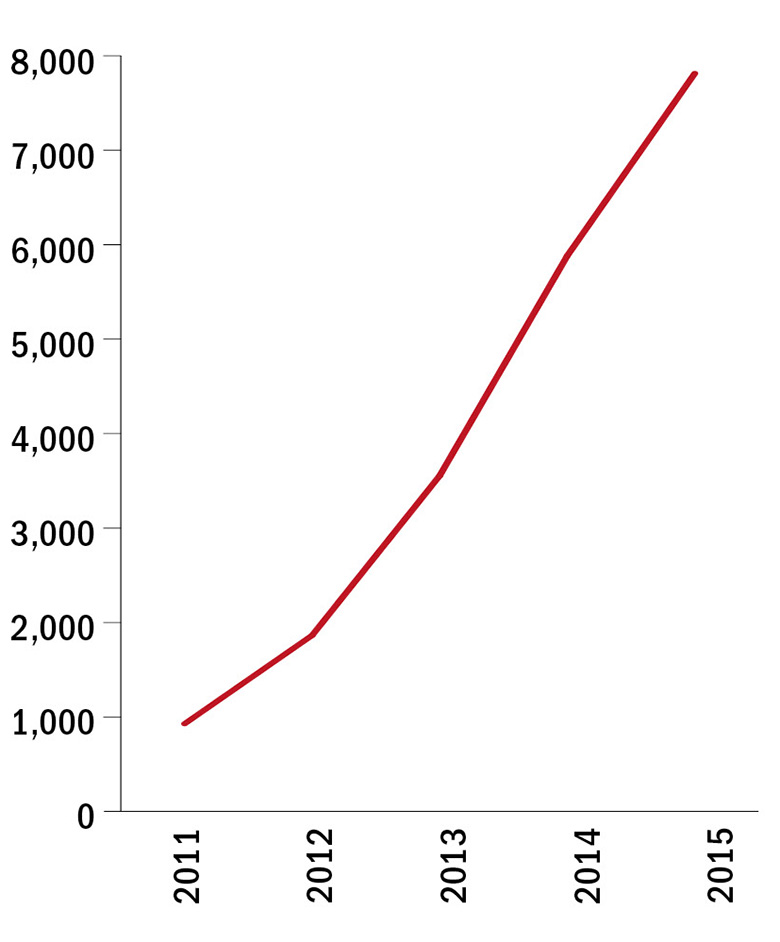

Degree-seeking Chinese students in Taiwan

Source: Taiwan Ministry of Education

Part of the pressure to publish well undoubtedly comes from international university rankings – via which, Chang says, Taiwan aspires to demonstrate its strengths.

“Taiwan has always had a desire to be seen, and to be heard, since diplomatically we are quite silent,” she says, highlighting the difficulties caused by not being recognised as an independent state. “I think that there is a psychological side. People really want their academics and their universities to perform well.”

Indeed, another of the bugbears of China Medical University’s Wen-Hwa Lee is that Taiwan’s research environment compares unfavourably with those of Singapore and South Korea, two regional competitors and fellow “Asian tigers” (as they and Hong Kong were christened in the 1960s), which, he feels, have acted more swiftly to push the importance of a strong university sector.

Hence, while few things can cause a room full of senior university leaders to fall silent, it was possible to hear a pin drop when the results of the THE Asia-Pacific University Rankings were handed out to presidents and provosts from across the region at a reception hosted by Asia University in Taichung earlier this year. The majority of those in attendance were from Taiwanese institutions, and all were intent on discovering how their universities had performed in comparison with those from East Asia’s better-known higher education powerhouses, such as Japan, Hong Kong and South Korea.

Indeed, Taiwan is set on building more of a regional presence, thereby lessening its dependence on mainland China. Last September, for instance, the government announced its “New Southbound Policy”, aimed at building relationships with 18 countries across Southeast Asia, South Asia and Australasia. The programme aims to offer scholarships for up to 60,000 students from members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to study in Taiwan by 2019.

But that is unlikely to be enough to save its university sector from some serious contraction without a significant influx of students from the mainland.

“That is how you can make some money,” says Chang. “If there are not enough local students, you need to attract more students from abroad. What is the main source you can draw from? It is China.”

A brief history of Taiwan’s relations with mainland china

China views the island of Taiwan as a renegade province that should – and one day will – be reunited with the mainland (using military force if necessary). Notwithstanding, Taiwan’s 23 million people have lived under a de facto independent democracy since the Communist Party of China claimed victory on the mainland over the old Republic of China at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949.

Taiwan, then, is in effect the last remaining part of the defeated Republic of China. It was able to remain independent because of the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, during which the US stepped in and in effect gave Taiwan a security umbrella.

Decades of hostile rhetoric between Taiwan and China ensued, with relations only thawing in the mid to late 1980s, when China proposed the “one country, two systems” plan, which would grant Taiwan significant autonomy if it accepted reunification with China (much like the settlement offered to Hong Kong). Although the deal was rejected, Taiwan did relax visa rules, and declared in 1991 that the war with the People’s Republic was over.

There have been bumps in the road since, however. In 2000, Taiwan elected President Chen Shui-bian, who had backed formal independence. After he was re-elected in 2004, China passed laws that would allow it to use “non-peaceful means” against Taiwan in the event of any independence bid.

Relations improved in 2008 with the election of Ma Ying-jeou, who implemented a number of economic agreements with the mainland. At this time, it also became possible for larger student exchanges to take place between Taiwan and China.

In 2014, Taiwan’s parliament was occupied by hundreds of students for weeks, in protests known as the “Sunflower Movement”. Those taking part demanded more transparency, and expressed concern about China’s economic and political influence in Taipei.

Last year, a new president, Tsai Ing-wen, was elected, and subsequently refused to recognise Beijing’s “one China” stance. She also accepted a phone call from newly elected US president Donald Trump, who himself was breaking with protocol since the US cut formal relations with Taiwan in the late 1970s.

These developments have touched a nerve in Beijing, and in March, Chinese premier Li Keqiang said that China would “never tolerate any activity, in any form or name, which attempts to separate Taiwan from the motherland”.

Chris Parr

后记

Print headline: A buyer's market