It says a lot about British attitudes towards education and hierarchy that a change in institutional naming and governance regulation that occurred a full three decades ago this year still stirs controversy.

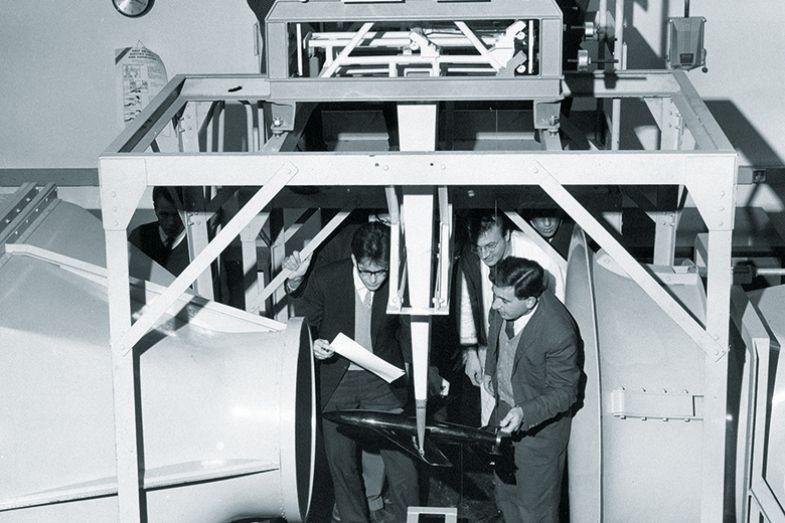

The term “polytechnic” was in widespread use for less than 30 years. The creation of officially designated polytechnics was heralded in a 1965 speech by Labour education secretary Anthony Crosland, who firmed up the existing “dual system” split – between “autonomous” universities and “public sector” technical colleges and colleges of education – to carve out from the latter a separate sector meeting demand for “vocational, professional and industrially-focused” courses. Yet the 34 polytechnics to which a Conservative government gave degree-awarding powers and redesignated as universities in 1992 are still sometimes referred to as “former polytechnics” – and very often as “post-92” institutions.

For some, that label is a badge of honour, the abolition of the so-called binary divide between universities and polytechnics marking a major step towards greater social equality. But in certain media and political circles, “post-92” is the mark of an institution that is still inherently inferior to “pre-92” institutions – some of which also had their origins in technical, science or arts colleges of the Victorian era. For these critics, 1992 marked a damaging turn away from vocational education towards an era of costly university expansion that has brought insufficient economic reward.

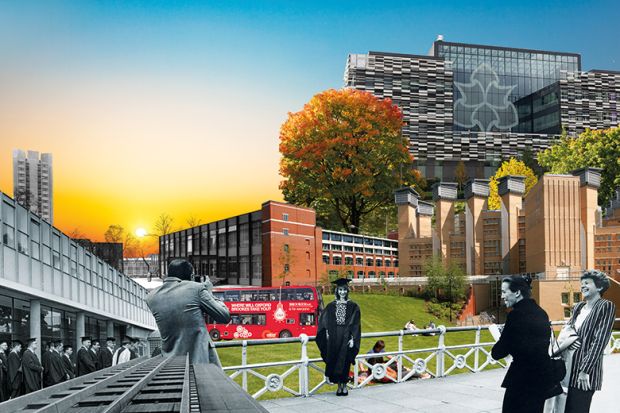

Former polytechnics (and their Scottish cousins, the former central institutions) have certainly played a key role in higher education expansion. In former industrial towns and cities of the English Midlands and North, such as Wolverhampton, Stoke, Middlesbrough, Sunderland, Preston and Huddersfield, the local post-92 university is the sole higher education institution. Such universities are also significant drivers of local regeneration; their estates probably include not just brutalist relics from the polytechnic era, but more modern glass-and-steel buildings, too – built with university-level resources (including international student fees, perhaps) to accommodate a mushrooming student population that also comes with a significant income boost for the local area.

Go to the centre of a big city like Birmingham, Sheffield or Nottingham, meanwhile, and you are likely to encounter tens of thousands of post-92 university students walking between classes five minutes before every hour. Among English campus universities, the three biggest recruiters of UK students – all with more than 30,000 – are post-92s: Nottingham Trent (33,590), Manchester Metropolitan University (33,155) and Sheffield Hallam University (30,260). In fact, post-92s make up 12 of the top 20, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency figures (13 if you discount the Open University).

Their students often come from less advantaged social backgrounds than those on the leafier campuses of the pre-1992 institutions, mostly (though not in London) located further out from the city centre. But those students often go on to highly successful careers in a wide range of important UK sectors. In that sense, post-92s are often described as doing the “heavy lifting” on social mobility. So why is it that 1992 is still seen by some as the moment higher education policy in England took a wrong turn?

Thirty years on, and with skills and employability high on the political agenda, now is a good time to reflect on that question, and to re-examine the impact of the post-92s on UK higher education and society.

The background rumble of laments for the loss of the polytechnics has the potential to bring some policy lightning flashes from Westminster. Baroness Wolf, Sir Roy Griffiths professor of public sector management at King’s College London, a panel member on the Augar review of English post-18 education, and now skills and workforce adviser in the Number 10 Policy Unit, wrote in 2017 that the loss of higher education institutions “with close links to local labour markets” and a “stress on part-time, adult study” put the UK “out of step with the rest of the world, and it was barely discussed at the time”.

One popular theory about what drove the 1992 changes is that the Tory government wanted higher education expansion and the polytechnics were willing to offer it at a cheaper rate – if they could have university status to attract more home and (fee-paying) international students.

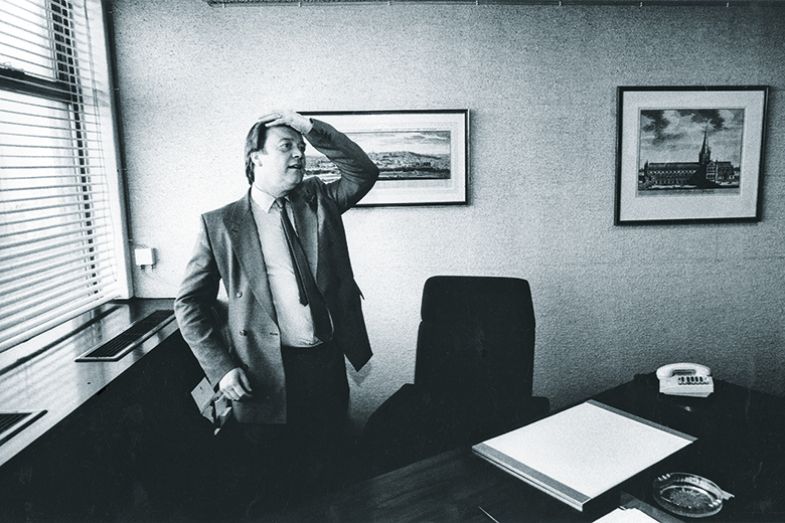

However, that “expansion on the cheap” theory is described as “cynical nonsense” by the man who abolished the binary divide: Lord Clarke, then education secretary in Sir John Major’s government.

In reality, the most important driver of the decision “was the fact that the polytechnics were suffering from the continuing British problem that any technical, engineering or occupational-based education was regarded as second class compared with traditional education at universities”, Clarke tells Times Higher Education.

The polytechnics, he continues, would have been classed as universities “in any other European country” and it was “just absurd” that they were “regarded by schoolteachers, by parents guiding their children, as an unfortunate second division to which you had to go if you were unable to get into a university”. This was particularly true given that “three or four of the polytechnics were undoubtedly much superior institutions to some of the weaker universities”.

Clarke did not “go round trying to score points about increasing the number of university students”: his aim was simply to “raise the status” of the polytechnics’ vocational and technical education, “areas which British society and the British economy needed to be stronger in”.

So what is the legacy of Clarke’s landmark decision?

Rachel Hewitt, chief executive of the MillionPlus group of post-92 universities, says the abolition of the binary divide “remains an important milestone in UK higher education, enabling hundreds of thousands to take higher study who might not otherwise have had the chance”. The anniversary offers an opportunity to “remind ourselves how important our diverse HE system is to Britain, economically and in soft-power terms”.

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor of the University of Sunderland and the former permanent secretary at the Department for Education, says the creation of “new” universities was crucial in raising aspiration to attend university – and, thereby, made it much easier to realise the subsequent Blair government’s target for 50 per cent of young people to go through higher education. “So I have no doubt that it was an important – and, indeed, vital – macro-level social mobility intervention,” he says.

On the other hand, argues Peter Mandler, professor of modern cultural history at the University of Cambridge, we should not fixate too much on the “tiny little levers” that politicians pull when factors like student demand are far more powerful drivers of expansion.

“People have the most ludicrous myths about this process,” says Mandler, author of the 2020 book The Crisis of Meritocracy: Britain’s Transition to Mass Education Since the Second World War. “They think that expansion only happened because they renamed the polytechnics…[but] you couldn’t treble the numbers in higher education without every university growing,” he says. Massification has been an international phenomenon and, by the early 1990s, the UK “had a lot to catch up” after having “slowed things down” prior to the 1980s, he adds.

As to how that all looks on the ground today, post-92s are distinguished not just by their size but also by their innovation. Coventry University, for instance, has established a London campus (helping it attract more than 13,000 international students); a lower-cost subsidiary, CU Coventry, tailored to part-time learners with lower entry grades; and a branch campus in distant Scarborough, a previous “cold spot” for higher education provision.

Other former polytechnics have acquired significant social cachet: perhaps even too much. For instance, Oxford Brookes University last year attracted headlines for recruiting a high proportion of students from private schools.

In 2019, meanwhile, Sunderland expanded its locally focused healthcare offering by opening a medical school – traditionally the preserve of Russell Group universities. The university is also a partner, with the local council and a local arts and culture organisation, in a joint venture managing five local venues: the aim is to enhance the city’s cultural profile in order to boost its creative economy and the aspirations of its young people.

Indeed, while it is fashionable in higher education to talk of a new civic consciousness, many post-92s can claim to have had one from the start – and to be in the vanguard of the current movement. Sheffield Hallam, for instance, is flexing its power as a major centre for teacher training and educational research through the South Yorkshire Futures programme, which – in collaboration with local councils – aims to raise school attainment across a region hit hard by the loss of mining and steel jobs in recent decades. The programme includes a university-run nursery and a mentoring programme reaching about 2,500 pupils this year.

Unlike many post-92s, Nottingham Trent draws 70 per cent of its students from beyond its region. It is thus a “major skills importer into the East Midlands”, meaning it can build a “financial base to do things for the city and the region we couldn’t otherwise do”, says its vice-chancellor, Edward Peck. And it is increasingly unconstrained by traditional notions of what a university should or shouldn’t do. According to Peck, who was a member of the Augar panel alongside Wolf, it has begun to “worry less” about the question “What does it mean to be a university?” Instead, “we’ve moved on to ‘What does it mean to be a major player in our local economy in terms of skills and innovation?’”

Polytechnics’ acquisition of university status entitled them to bid for public research funding. And while Russell Group institutions have largely maintained their hegemony in that sphere, some post-92s have developed what are often called “pockets of excellence”. For instance, Nottingham Trent has particular research strengths in the prevention of sex offending and in medical technology – the latter linked to the city’s most famous corporate creation, the pharmacy chain Boots. Nottingham Trent criminologist Loretta Trickett and University of Nottingham linguistics professor Louise Mullany won the award for “outstanding contribution to the local community” at last year’s THE Awards for their research evaluating the impact of Nottinghamshire Police’s treatment of misogyny as a hate crime.

Meanwhile, in 2019, Nottingham Trent announced a major partnership with Vision West Nottinghamshire College, providing higher education programmes at the further education college’s main campus in Mansfield, a former mining town struggling with the legacy of deindustrialisation. The students studying in Mansfield are 70 per cent local and 70 per cent mature – which suggests that the upskilling being delivered will stay within the local area. “We’ve got 95 local people studying nursing in Mansfield. They will do their placements in Mansfield and get a job in Mansfield because they don’t want to go anywhere else,” says Peck.

That is the kind of thing Ray Cowell – the vice-chancellor who led Nottingham Polytechnic into the university era – has in mind when he says that since becoming a university, the institution “has developed its research capability while expanding what I call its vocational, polytechnic qualities”.

With such a range of characteristics among this group of institutions, does the 30th anniversary of the binary divide’s abolition, or the label “post-92 university”, really mean much today?

Cowell notes that while the 1992 act created a large number of new universities “at a stroke”, Nottingham Polytechnic had in mind a more gradual, individually focused validation process. The “one fell swoop” approach meant, he argues, that “media such as the [right-wing Daily] Telegraph persisted in calling us ex-polytechnics for a couple of decades. There was a feeling that we sort of muddied the water and debased the university title.”

Yet since the conversion of the 34 polytechnics (the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act also allowed two colleges of higher education to become universities, today’s University of Bedfordshire and University of Derby), the successive further easing of the path to university title has added a further 48 “modern” universities – as they sometimes like to be known – to the register, in a larger wave of expansion. These figures are cited by Sir Chris Husbands, vice-chancellor of Sheffield Hallam, who argues that “the only real interest in talking about the [binary] divide is now among some of the weaker pre-92s, who have seen their position and status eroded by a vibrant, successful and large clutch of modern universities”.

Rather than looking at the “minor issue” of the binary divide, Husbands thinks it is “much more important to think about diversity across the sector – there is diversity within the pre-92s and diversity amongst the post-92s”.

Yet others think 1992 failed to truly shift, or perhaps even ended up deepening, the hierarchies of English higher education. As noted by Sir David Eastwood, former University of Birmingham vice-chancellor and former chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council for England, “almost coincident with the abolition of the binary line was the rise of the Russell Group” – the group of large research-intensives that have successfully established themselves in the popular imagination as the country’s most prestigious universities.

The 1992 changes “didn’t invent hierarchy”, Eastwood adds. But “what we’ve seen in the 30 years since 1992 is university brands becoming more important, university clubs [such as the Russell Group] becoming more important and the inexorable rise of rankings of universities”.

In the modern era of higher education, students from non-traditional backgrounds have tended to go into post-92s, observes Mandler. “I think that’s been an achievement: it’s allowed us to raise our participation rates. But it does mean, of course, that stratification continues – and in reality: it’s not just a perception.”

And that enduring “rigid hierarchy” of institutions, as Mandler puts it, arguably feeds into government policy. The DfE and Office for Students often look at universities through the metrics of graduate earnings and jobs outcomes. The courses they deem “low value” are often those that recruit high proportions of disadvantaged students, particularly in some of the post-92s located in the more deprived suburbs of London.

Moreover, the current Conservative government appears increasingly sceptical about the economic value of expanded university education. That attitude is arguably embodied in its plans, announced in its recent response to the Augar review, to potentially restrict entry to universities and shift more provision away from full degrees towards shorter “technical” courses. Does that stance betray some regret at the loss of the polytechnics or the era of expansion that ensued?

“This is a definitely a common refrain among Conservative members and MPs – particularly those who are not especially close to the detail of policy,” says Jonathan Simons, partner and head of education practice at the influential political consultancy Public First. However, “within government, I think there’s a view that institutions ought to specialise more – and that there ought to be routes for quicker, more labour market-specific courses for young people and career changers. Whether those are from new polytechnics, or universities, or Institutes of Technology, or whatever, is generally less clear.”

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and former adviser to Conservative universities minister Lord Willetts, says: “Clearly, there are parts of Whitehall that would be happy for some former polytechnics to revert to what [parts of Whitehall] perceive to be their previous role, with deeper local roots and lots of sub-degree provision. But this probably misrepresents the role many polys were actually playing.”

For her part, MillionPlus’ Hewitt detects very confused attitudes from politicians given that post-92 universities are often doing precisely the thing that they say they want more of. “Some in politics and the media seem to choose to continuously bash this part of the university sector…[yet] every week, we hear politicians talk about levelling up or skills shortages or a lack of technical education – without recognising that the answer to these questions is right in front of them.”

So what of the future for post-92s? An institution like Staffordshire University, which offers higher technical qualifications and has about 2,000 apprentices, has to be closely aligned to local business needs, says Liz Barnes, who retired as the Stoke-based institution’s vice-chancellor in December. Such institutions have to “continually think about relevance…probably more so than the traditional Russell Group-type universities,” adds Barnes, who also worked at post-92s Sheffield Hallam, Teesside University and the University of Derby.

It is post-92 universities that provide the courses tailored to new economic needs and that are best equipped to drive further curricular innovation, many argue. When Teesside first introduced computer games courses, says Barnes, “it was very much about the games industry; now it’s about gamification. I spoke to a medical technology company that said every one of its engineers was a games graduate. I just don’t think the government recognises the importance of universities of today for providing the workforce of tomorrow.”

There is huge potential change coming for higher education – and arguably for post-92s in particular – in the shape of the government’s planned Lifelong Loan Entitlement, the creation of Wolf. Scheduled for introduction in 2025, the LLE will allow adult learners to access loan funding for four years of post-18 education, which could be used to study a single module or build up a full degree over time.

Peck foresees such innovations having a “transformative” effect on Nottingham Trent. “I think what we’re starting to see here is a bit of a ‘back to the future’ [dynamic]. As we move into the LLE, microcredentials, short courses, flexible learning, credit transfer, NTU will start to look a bit more like it used to look back in the ’60s and ’70s, with lots of students studying part-time, studying in the evenings, studying at weekends…If it’s necessary and helpful to the local economy and local people for us to go from level 2 [GCSE] through to level 8 [PhD], then we will.”

But does this potential return to the polytechnic ethos cast a shadow over the future of some non-vocational subjects? Sunderland, for instance, made a controversial decision two years ago to exit languages, history and politics subjects – sensing the policy wind.

“I can’t speak for everyone, obviously, but I think that a university like Sunderland has, in some ways, returned to its distinguished polytechnic roots as a university focused on the applied, vocational, practical – with that now including everything from medicine, through engineering, to the creative arts,” says Bell, its vice-chancellor.

One of the big questions is what effect the government itself intends the LLE to have on universities, particularly post-92s. Is it intended to divert demand from deemed "low value" full degrees to cheaper, shorter, vocational courses, leading some institutions towards a more “polytechnic” profile? Undoubtedly. But significantly shrinking some universities in terms of size and resources might undermine the role that they can play in the government’s overarching priority of “levelling up” in the UK regions – something many post-92 universities and their ancestor institutions have quietly been doing since Victorian times.

“The only way we’re going to level up in places like Stoke or Middlesbrough is by upskilling the [adult] population that never had the opportunity to go to university,” says Barnes. As essential institutions in such deindustrialised cities and towns, whose reach already extends to adult learners, the post-92s might look as though they should meet government priorities.

“We need more universities in deindustrialised parts of the north of England,” agrees Mandler. “The polytechnics…gave [higher education] a foothold in places where higher education would otherwise never have been established.”

Despite a shifting policy focus towards further education colleges, the FE sector remains underpowered, meaning that levelling up through education will require further and higher education institutions to work together. Like it or not, the acquisition of university status has allowed post-92s to expand and generate a level of income such that their regional clout is sometimes unmatched by any other institution. There are “not many big businesses around our area,” says Barnes of the Stoke region. “You’ve got the NHS, you’ve got [online gambling company] Bet365 and you’ve got the university.”

In a nation like the UK, however, with its steep social hierarchy replicated in its education system, any “new” university faces a battle.

Even Clarke concedes disappointment that “too many of the polytechnics…celebrated their new status” by creating “second-rate arts departments”. But overall, he says ending the binary divide “was successful. I think it’s had a very worthwhile effect. Some institutions [among] the former polytechnics have thrived on a great scale.”

Critics of higher education expansion often seem to ignore the far bigger economic picture when they bemoan the loss of the polytechnics and the supposed turn away from the “vocational” and “applied”: that the UK’s rapid deindustrialisation since the 1980s might have taken away a large amount of demand for such courses. Countries that did a better job of managing deindustrialisation, such as Germany, have maintained stronger vocational education.

And rather than fixating on polytechnics, perhaps there should be more focus on why the older universities, now in the Russell Group, shed their extramural continuing education departments for adult learners from the 1980s onwards.

Either way, Hallam’s Husbands is adamant that England’s university system, 30 years on from the abolition of the binary divide, is “world class”. His concern is that political currents – such as inflexible metrics that don’t take account of regional and institutional contexts – risk creating less rather than more diversity. “Looking ahead, without a clear sense from government of the importance of diversity and collaborations between universities which differ in mission and vision, we may have a handful of world-class universities, but we won’t have a world-class sector,” he warns.

The American writer William Faulkner famously wrote: “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” The decision to allow the polytechnics to become universities is a good illustration of that adage, still underlying the policy debate today. But as many post-92 universities play a key role in levelling up, meeting the needs of local economies and catering for the kinds of adult learners who will use lifelong loans, they can make a justifiable claim to be a big part of the future.