I have an abiding memory of an elderly neighbour’s death and the subsequent house clearing conducted by her offspring. A skip was parked at the front door and literally everything was tipped into it: not just her clothes, her books and her kitchen equipment, but also the photographs, letters and diaries that, I supposed, might have been her most treasured possessions.

I knew of these not because I was tempted to “skip surf” myself, but because I saw another old neighbour doing it. As he passed the skip with his dog, he stopped and began stirring the contents with his walking stick, apparently musing over these records of a life that, whatever their value to the old lady might have been, were evidently worthless to her children.

Naturally, after such a sight, I was led to reflect on what will be left of my own life when I am gone, and who might value or discard its relics. So, as I prepared recently for another house move, I trawled through those old lecture notes that, for some unknown reason, I still have.

There were those that I took during my undergraduate degree. From 17 February 1971: notes on Max Weber’s historical sociology; 21 March: Raymond Aron on Durkheim. Would you believe I used to date-stamp my notes in those days? Then there were also the notes that I used to write at four in the morning during the initial year of my first full-time teaching post, for lectures to be delivered the very next day – probably at nine in the morning.

I was led to reflect further on why I had even paid to have all this “stuff” removed from storage in the UK to the French barn I was about to leave. My wife has often said, eminently rationally: “If something hasn’t been used for two or three years, how can it be seen as useful?” Well, it had been eight years since I retired and I hadn’t needed, used or read those lecture notes, so off they went to their final resting place – the bin. But why on earth did I reread them even then? Sentiment, pride – or bewilderment at the intellectual ground I appear to have covered? Fortunately, the look of disgust on my wife’s face cut short the reminiscences – and the promise of a brandy with my coffee expedited the notes’ demise.

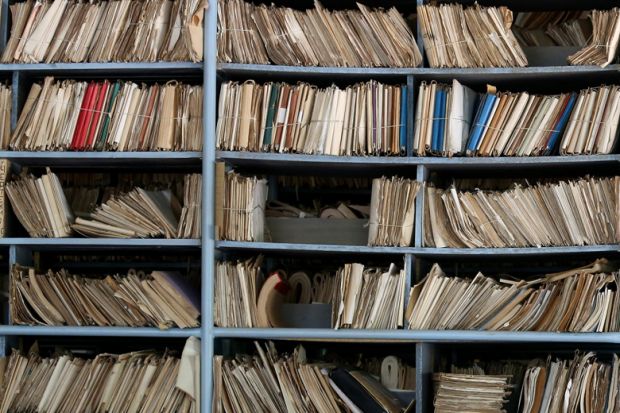

I have seen so many dramas involving ageing academics who prepare for their own deaths with a backyard bonfire. But how many more will there be, in this electronic era? Surely work done in the past 20 years will not so much be gathering dust on a shelf as lingering silently in obscure folders of a hard drive that no one ever feels the need to delete. That, in itself, is a peril to a natural hoarder like me: you wouldn’t believe what I have managed to archive, after transfer from floppy discs (remember them?) to a 60-gigabyte flash drive.

So, following the departure of my paper relics, what will be left after I have gone is the apparently immortal contents of my hard and flash drives (which I must not be tempted to start rereading and deleting: the disdainful glance from my wife would be too hard to bear). If those devices end up in a skip, there will not even be anything enticing to stir through with a cane. It is a sobering thought.

It is even more ironic that I devoted a chapter in my last book to advising readers exactly why and how they should “let go”. To be fair, though, I do have a clause at the beginning excusing my own occasional inability to follow my own very sound advice.

So when exactly should you let go? When, as my wife would have it, you can no longer think of a useful outlet for your notes, musings or intellectual reflections? Or, perhaps better, when any rereading provokes no stimulus to writing or to further philosophical reflections: merely a sentimental “staring at the past”?

Ron Iphofen is an independent research consultant. His latest book, 49 Ways to…Pull Yourself Together, was published by Stepbeach Press in 2015.

后记

Print headline: All my unvisited archives