Source: Miles Cole

It is perhaps an odd question, but have you noticed how slithery popular gothic culture has got lately? The vampires looked simply exhausted in Jim Jarmusch’s film Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). The mummies have dutifully shuffled back to the British Museum for a brilliant new exhibition, Ancient Lives, New Discoveries. Move over zombies: if you want an emblem of contemporary horror, you could make a strong case that this is the Time of the Tentacle.

When did this start? Was it that alien bursting out of John Hurt’s chest in Alien in 1979? Lots of gooey stuff followed: Jeff Goldblum’s nasty transformation in the 1986 film The Fly, Sil’s unusual mating habits in Species (1995), the writhing tentacles that reach out of the fog in The Mist (2007) or in Monsters (2010) or that creature that bounces around Seoul harbour in The Host (2006). When the Men in Black (1997) confront an illegal alien, they shout: “Put up your hands! And all of your flippers!”

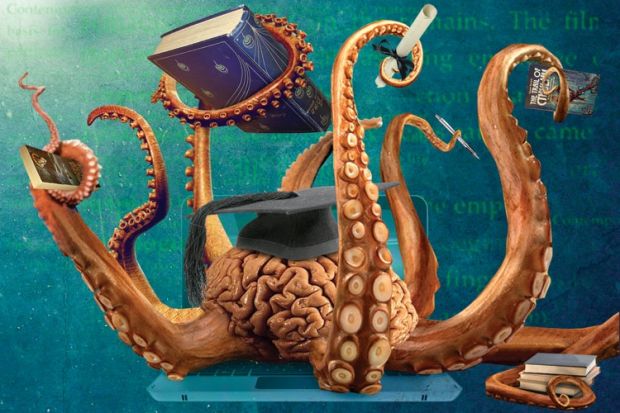

Away from the screen, since 2003 there has been a significant literary movement called The New Weird that features octopuses, vampire squids and slightly stranger cephalopods with startling frequency. It is a fusion of science fiction, gothic and European surrealism, all largely stuck together with mucus.

The multi-award-winning author China Miéville (who has an octopus tattoo, naturally) brought this to a head with his novel Kraken in 2010, which was about a cult of giant sea monster worshippers in London. It was, appropriately enough, shortlisted for the Red Tentacle award, for a work that contains elements of the fantastic, at the Kitschies – possibly the geekiest annual prize ever invented. As the name suggests, The New Weird harks back to early 20th-century pulp fiction, the era when H. P. Lovecraft first published his “weird tales”, nightmarish stories of our Medusoid ancestors, slimy gods like Cthulhu, worshipped by depraved and degenerate half-men. Lovecraft, not a fan of seafood or of any non-Aryan races, fantasised about horrific miscegenation between men and fish in the decayed old villages of New England.

He has become a rather surprising resource for a whole new school of critical theory in the 21st century, sometimes called weird realism. These young scholars publish articles with titles such as “Mucosal Monsters”, or books like Ben Woodard’s Slime Dynamics (2012) or Vilem Flusser and Louis Bec’s Vampyroteuthis Infernalis: A Treatise (2012).

What is going on?

I tried to ask this question earlier this month at the Higher Education Academy’s annual humanities conference, Heroes and Monsters: Extra-Ordinary Tales of Learning and Teaching in the Arts and Humanities, only to find my talk upstaged by the breaking news that a lorry carrying a giant octopus had broken down in the middle of Oxford Circus. Yes, really.

Academics often think of the gothic as an allegorical genre. We conventionally say that the devices of the genre are ways of confronting and discussing anxieties or fears, and that gothic tropes change as these fears change. It is common, for instance, to “translate” the zombie horde, the undead scrabbling away at the windows and doors, as a vision of the alienated world of work under modern capitalism. Or else those hordes are a vision of the global poor, an image of social inequality suitable for a world in which everyone has read, or has pretended to read, Thomas Piketty. The same goes for the vampire or the haunted house: they are easy to “translate”.

The slithery cephalopod can of course be read through the familiar gothic trinity of significance: sex, death and money. There is, should you dare to search for it (maybe not on your work computer), a large genre of “tentacle erotica”, all stemming from Hokusai’s famous 1814 painting, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. Meanwhile, Victorian biologists were inspired and appalled at the prospect of our evolutionary origins in protozoic slime. Anti-capitalists, meanwhile, have long used the octopus as a symbol of the grasping multinational corporation: it’s how Standard Oil was depicted in 1904, long before Goldman Sachs was denounced by the Occupy movement as a “vampire squid”. (This prompted the internet meme “Octopi Wall Street!”)

I think of the tentacle, however, as an emblem of genuine “otherness”, something that we ultimately find very hard to “translate”. Animals like the giant squid, one of the largest creatures on the planet, exist in a hinterland between myth and science, the tall tales of sailors down the centuries. We still know little about these creatures: how they live, their life cycle, their habits.

Biologists argue over where they fit in taxonomies: they remain a crisis of category as such. Their sex life is truly amazing (some octopuses have three penises and the reproductive act lasts for months), and their communication through epidermal colour changes, and sculpting shapes with their tentacles in the ink they eject, are way beyond our limited understanding of non-human “language”.

In May, scientists issued further findings on the weirdly distributed nervous system of the octopus, which means, in effect, that each of its eight limbs is autonomous from the others, and that each limb can survive and operate for a while even after it has been severed from the body. They still don’t know how the brain of the octopus works or why the creature doesn’t tangle itself in knots. And they are hard to study because in captivity the octopus has the tendency to eat its own tentacles, to commit suicide rather than become objectified.

The octopus is, in neurological terms, undoubtedly our evolutionary superior.

What is instructive about this is the limit to what we can learn. We’re always authoritatively interpreting things for ourselves and for our students. But the tentacle can be a sign of absolute alterity, the creature feature that man cannot translate into allegory or object lesson. This is what I call “tentacular pedagogy”: the teachable moment is that some things we encounter completely resist being translated into teachable moments.