Recently, I was at an academic conference in Boston, Massachusetts, and took time out to visit the Grolier Poetry Bookshop. Located just off the campus of Harvard University, this fine establishment has been supplying poetry exclusively since 1927. It is beautiful: a small place that treasures books as material objects and exudes a calming presence, wonderfully suited to the rarefied pleasures of slim books of verse. I browsed and soaked up the atmosphere, admiring the numerous photos of visiting poets before buying an obscure volume and leaving feeling recharged.

How much longer will such temples to literary culture continue? I suspect all academics of a certain age will have memories of a favourite bookshop, but do such establishments still hold a special place in the hearts of younger academics – never mind students? How could they, when so few people these days live anywhere near one of those disappearing “small good places” – as sociologist Ray Oldenburg describes the kinds of independent bookstores, cafes and bars that form the heart of communities.

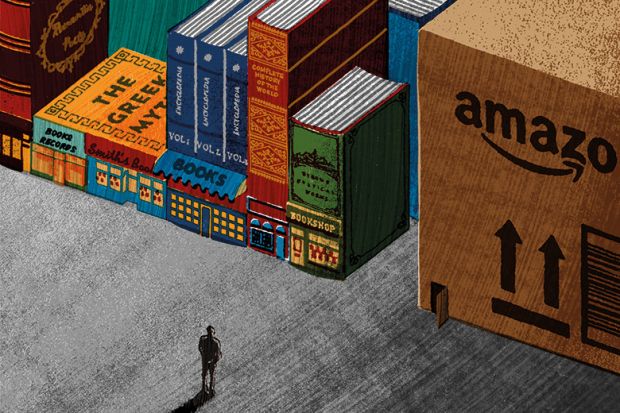

We academics might still give our undergraduate reading lists to our campus bookshop, but do we – like 72 per cent of our students, according to Nielsen’s Students’ Information Sources in the Digital World 2015–16 report – buy our own books online, aware that time spent browsing in a physical bookshop is time away from more pressing academic tasks? The giant online retailer Amazon – the feared enemy of physical bookshops – now even has a pick-up point on campus at the University of California, Berkeley, from which you can order and pick up your books; with about 40,000 students enrolled there, I am sure that it is doing good business.

In carrying out research, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, on the history of the modern bookshop, I have become intensely interested in the current state of such establishments. A few years ago, they appeared to be in a state of terminal decline. According to an article in The Daily Telegraph in 2011, nearly 2,000 had closed in the UK since 2005. The number of independent bookshops has been declining by around one a week, and the total number currently stands at about 900. Even the big chain booksellers, partly responsible for the decline of independents in the 1980s and 1990s, were threatened by Amazon and its ilk, and the bankruptcy of Borders in 2011 seemed to signal that the days of physical bookshops might be coming to an end.

However, in 2015, Oren Teicher, head of American trade organisation the American Booksellers’ Association, announced a rise in new independent bookshops, boldly claiming that “we are engaged in decoupling the word ‘endangered’ from ‘bookstores’”. In the UK, their closure rate is slowing, and the Publishers’ Association this year revealed that sales of print books were rising again, for the first time since 2011. Of course, some of this rise could have occurred online rather than in physical locations, but the decision of Amazon in 2015 to open its first proper bricks-and-mortar store, in Seattle (with more reputedly to follow), is surely significant.

The endurance of bookshops is due to more than simply the sale of books, however. In recent years, they have increasingly incorporated cafes, author readings, book groups and exhibitions. A well-designed spatial environment, as in the revived Foyles on London’s Charing Cross Road, is also a great attractor. The Last Bookstore in Los Angeles is perhaps the last word in “destination bookshops”: those visited by tourists for the experience of their interiors rather than the quality of their stock. Traditionalists might blanch at the use of books as architectural features, as in the hundreds used to support the cash desk or to carve out the impressive “book tunnel”. But for anyone who has ever been entranced by the quiet, dimmed, quirky charms of a bookshop, it is certainly worth a visit.

Given the changing commercial tides, it is perhaps unsurprising to hear, back in the UK, academic bookseller Blackwell’s announcing recently that it will trial two “enhanced concept stores” at the universities of Cardiff and Liverpool, complete with cafes, seating and digital display screens – all aimed at integrating the company’s physical and online operations and offering students a more social experience than that offered by traditional academic bookshops. The company could do worse than take a look at The Last Bookstore if it is really serious about encouraging students to rediscover the pleasures of physical browsing as part of a wider hipster culture that also takes in craft beers and vinyl records (The Last Bookstore has a very good vinyl section – although, so far, no bar).

Even in the absence of such bold gestures, the Nielsen survey suggests that bookshops retain an important function in the student experience. Of UK students buying new print titles during the 2015-16 academic year, 84 per cent had bought at least one book from a physical bookshop. Not surprisingly, Amazon still dominates the student market, with 70 per cent of respondents having bought from it, although the share of total volume sales had grown in campus bookshops.

So while the future for independent bookshops may still be uncertain – especially if Amazon replicates its rather soulless Berkeley hangar on more university campuses – there are at least glimmers that small, good literary places can endure. And surely it can’t be mere Luddism or nostalgia to cling to that hope.

Andrew Thacker is a professor of English at Nottingham Trent University.

后记

Print headline: Small pleasures