Why would anyone want to think like an anthropologist? Or perhaps we should ask, rather, why anyone would want to think like a social anthropologist, for this is a book about social/cultural anthropology and it does not consider any biological subjects (such as how we’re here in the first place).

In many ways, the answer is simple: because that’s what all social anthropologists would like us to do. It’s something of an oft-repeated but rarely quantified trope (especially in university prospectuses) that the skills found in social anthropology are the key to unlocking the mysteries of humanity and are demanded hungrily by everyone from government and big business to the military. If only the world would recognise the inherent wisdom of social anthropologists, we’d all be much better off.

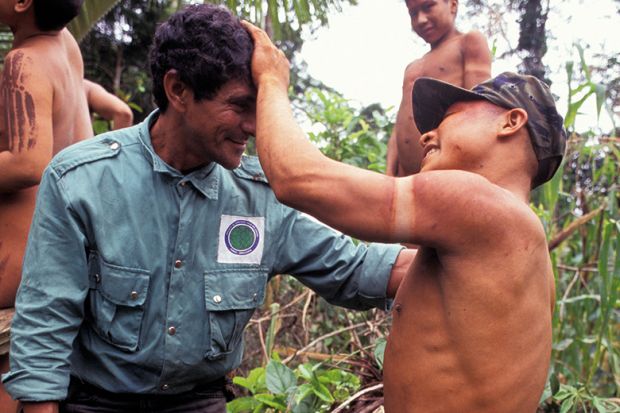

But there is a problem: by and large, social anthropologists write only for one another using impenetrably dense language and self-referencing theories that, ironically, would be worthy of ethnographic study. Public-facing or media-friendly social anthropology is exceedingly rare, and the few examples, such as Bruce Parry’s TV shows, are regarded with suspicion by “proper” anthropologists despite acting as many young people’s introduction to the subject.

Matthew Engelke’s brave book is an attempt to shine a light into the anthropological darkness and demonstrate that social anthropology and social anthropologists (for all their obfuscatory language) can offer genuine insights into the modern world and help to craft solutions to 21st-century problems. In this, it’s partly a success and partly a failure. This is mostly because of the way the book is structured, which is rather akin to explaining a joke – by the time you’ve done it, it’s not really that funny any more. In essence, the book can’t decide if it is about anthropology or is an anthropological book. In other words, too often you are left wondering why you would want to think like an anthropologist if this is how they think.

The sections when Engelke is telling anthropological stories and highlighting their value are excellent and carry the reader along with pace and verve. But too many sections are bogged down with anthropological fealty and reference to theoretical constructions that would be best left in the seminar room. The most glaring example of this comes from the early chapters that offer a potted history of the subject from a UK-US perspective and provide pen sketches of key thinkers and theories that soon get obscured by caveats and theoretical meanderings. The chapters dealing with broad concepts such as “identity” and “reason” are much better, offer a huge range of fascinating discussions of human diversity and are clearly the work of an author having tremendous fun with material he knows inside out.

Ultimately, the reader is left with the lingering impression that social anthropology has an identity problem and does not really know what it wants to be: a rather detached participant observer of humanity or a practical subject that acts as a conduit between peoples, organisations and governments in an increasingly complex world? This book shows that thinking like an anthropologist is something that we should all do more often, but anthropologists should also remember the advice of George Orwell and keep it simple when they write.

Simon Underdown is senior lecturer in biological anthropology at Oxford Brookes University.

Think Like an Anthropologist

By Matthew Engelke

Penguin Books, 368pp, £8.99

ISBN 9780141983226

Published 31 August 2017