“In a taxi headed to the Vegas suburbs,” writes Karen Klugman, one of the four authors of Strip Cultures, “my driver and I laughed about how he had once told some foreign visitors that the surrounding mountain ranges were just a fake backdrop and those innocents, probably having spent days under the faux skies in the resort hotels, had actually believed him.” This story, about two-thirds of the way into Strip Cultures, tells you a lot about the book and its approach to Las Vegas. A mordantly funny story, it puts the narrator at the centre of the action, and it depicts the city as a confusion of fantasy and reality in which the two are impossible to separate.

Strip Cultures underpins its thesis about fantasy and reality with some familiar cultural theory – Marc Augé’s Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Jean Baudrillard’s America, Roland Barthes’ Mythologies, the staples of postmodern cultural theory. Perhaps most prominent in the theoretical imagination of the book is Fredric Jameson’s account of the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, in which the philosopher finds himself entrapped in a space that seems to have been designed beyond the understanding of ordinary human beings. It is a case, in Jameson’s view, of the way contemporary capitalism sows the seeds of its own collapse. It’s mostly nonsense, but it has provided food for thought for a generation of cultural theorists, including this reviewer.

Strip Cultures also draws on a de facto tradition of writing about the cities of the American West, in which a liberal Eurocentric/East Coast scepticism is trumped by a fascination with the sheer abundance and inventiveness of culture freed from the usual constraints. In this category, I’d put the architectural historian Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, the classic Learning from Las Vegas by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, as well as the work of the activist/journalist Mike Davis, whose writing treads a fine line between condemnation and fascination.

So far, so predictable. If you don’t get beyond the first chapter or two, you could be forgiven for writing off Strip Cultures as a highly derivative piece of cultural analysis, becalmed somewhere in 1992. There were times when I groaned at Augé, Baudrillard and Jameson being invoked yet again, partly because of our overfamiliarity with these writers, but also because a few chapters in, it became clear that once these academic tics had been suppressed, this is a work of real distinction.

Hidden inside a cultural studies shell is a book of often startling richness and complexity, often very finely written. And it’s structurally unusual too, suppressing the normal conditions of authorship in favour of a collective mode that manages to be both personal and unusually ego-free. Part of my frustration with the reflex-like citation of postmodern cultural theory was that I thought the authorial team (Klugman, Stacy Jameson, Jane Kuenz and Susan Willis) were often simply better than the theorists they cited: sharper, more humane and more attentive to the complexities and contradictions (to borrow a phrase from Learning from Las Vegas) in what they described. Further, what they show is how far Las Vegas has moved on from what we knew of it in the early 1970s. It might have moved in the same direction, but it’s certainly not the same place it was. It is worth going back.

Why it is worth returning can be seen first in the length of the book: this is simply a much more substantial piece of work than previous studies, and the product of repeated visits over a period of years. There are more data, and a quality of depth to the observation. The authors’ observations of the minutiae of daily life in Las Vegas show not only how much the place has changed, but how much it has changed in relation to the rest of America. As they repeatedly show, Las Vegas acts as a repository for the forbidden, rather in the same way as the television series Mad Men allowed viewers to take a vicarious pleasure in chain-smoking, breakfast-time cocktail drinking and office-desk sex (“You’ll love the way it makes you feel,” declared Mad Men’s trailer, promising illicit thrills).

So Las Vegas is the place where an ever-more-proscriptive America lets its hair down. In one of the most suggestive vignettes, Jameson describes the city in terms of its “smellscape”, in which the predominant odour, in contrast to almost the entire rest of the US, is tobacco. “The smell of smoke lingers on the gaming floor; it is soaked into the carpets and chairs, and hangs onto the clothing of many of our fellow gamblers…Las Vegas seems to put the cigarette on a par with cocktails and gambling…Ashtrays are commonplace adornments of those gaps between one machine and another, permitting and inviting you to smoke.” For anyone familiar with contemporary American social mores, these notes seem – strange as it is to write this – almost shocking.

But in Las Vegas the normal rules do not apply. The same is true of alcohol, socially unacceptable in ever-increasing circles in the US. In Vegas, by contrast, it is acceptable, even semi-required, to engage in public drinking, and to this end the brewers supply branded coolers, de facto handbags big enough to keep a dozen beers on ice.

The city’s other big vice, sex, is explored through the phenomenon of “smutters”, the street hawkers of prostitutes, whose services the smutters advertise on semi-pornographic cards thrust at tourists as they walk past whether they want them or not (“the solicitors all flick their stack of cards in the same manner, which produces a regular clicking noise as if they are using sound to reinforce an addiction”). And running all the way through these vices like a golden thread is, of course, gambling, about which we learn a good deal, especially its evolution in recent years.

Punctuating each chapter are some outstanding photographs by Klugman, who also turns out to be the most talented of the writers on the team. Her pictures offer a kind of riposte to the colourful, Pop Art-inflected imagery of Learning from Las Vegas. Her tough, acerbic images show the lived city, rather than its surfaces: its tourists in all their shapes and sizes, its street hawkers and pedlars and, above all, its waste. A grimly beautiful still life on page 178 sums it all up: a sprawl of discarded beer bottles and smutters’ calling cards. It is an image that would have been inconceivable in any previous account of Las Vegas.

It sets the tone for the book’s final few lines, which alight on the tragedy of a young woman in the throes of a seizure that may, or may not, have been brought on by the city’s excesses. “We can still hear her as the paramedics load her into the ambulance,” write the authors. “‘I just want to go home,’ she cries. ‘I want to go home.’”

Strip Cultures is an admirably even-handed and non-judgemental account, for the most part, of a city whose openness allows its authors to experience it in some new ways. But as they make clear, it’s also a city whose pleasures come at a human cost. Without hectoring or harangue, but instead by steady accumulation of data and anecdote, that is the disturbing conclusion this book leaves.

Richard J. Williams is professor of contemporary visual cultures, University of Edinburgh. He is writing a history of the so-called creative city.

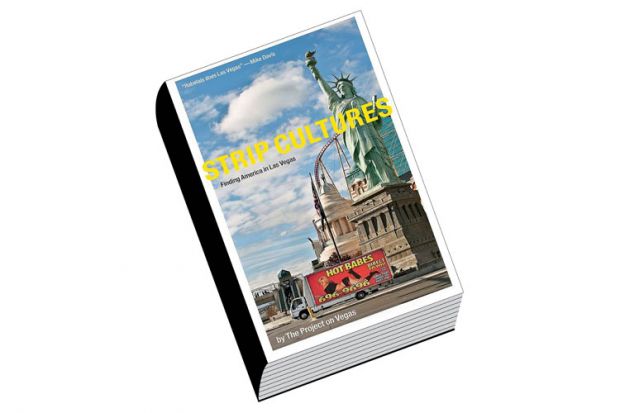

Strip Cultures: Finding America in Las Vegas

By The Project on Vegas: Susan Willis, Stacy Jameson, Karen Klugman and Jane Kuenz

Duke University Press, 384pp, £69.00 and £18.99

ISBN 9780822359487 and 9678

Published 2 October 2015

The authors

The Project on Vegas is “the product of multiple overlapping personal and professional relationships and interests”, says Jane Kuenz, associate professor of English at the University of Southern Maine.

Two of her three co-authors, Susan Willis and Karen Klugman, “were friends from Connecticut and had already collaborated on Susan’s book A Primer for Daily Life [1991]. Susan was one of my graduate professors in the English department at Duke University in the early 1990s, when we conceived and wrote Inside the Mouse: Work and Play at Disney World, which included Karen’s photos.”

Kuenz recalls: “After Inside the Mouse came out in 1995, Susan and I made plans to work on a sequel with Karen as photographer. Our first idea was Las Vegas.”

But they “drifted into other projects for a decade and a half, until Susan, Karen and I refocused on Vegas, at which point we were joined by [Susan’s daughter and co-author] Stacy Jameson. If anyone was really pushing the project then, it was Karen, who started taking a lot of pictures early on when the rest of us were still trying to figure out what we even wanted to say.”

The four authors’ experience of Las Vegas, Kuenz says, “varied by generation and geographical origin. My first visits to both Disney World and the Las Vegas strip were as an adult conducting research. Susan had significant experience at both places as a child and teenager growing up in California.

“Stacy’s relation to this project is most interesting since, as a child, she had accompanied Susan on family research trips to Disney World, where she also served as unwitting research subject. Now a mature scholar in her own right, she approaches the topic from a critical perspective quite different from the one Susan and I shared. She asks questions that never occur to the rest of us,” she observes.

Of the authors’ decision to credit the book to The Project on Vegas, Kuenz says, “The project name is important to us, not a makeshift solution or shortcut, but something we discussed and decided with the earlier Disney book and continued in this one. Strip Cultures is neither a single-authored monograph nor an edited anthology.

“The chapter topics followed from each writer’s own expertise and experience in Las Vegas. For example, I had already begun research on surveillance, social media and even the plastinated ‘Bodies’ shows at the Luxor before I wrote about any of them for this book. As a group, we met regularly to share and plan work, and we read and critiqued each other’s writing. However, with the exception of the single chapter on Vegas weddings, which includes three sections written by different people, each chapter in the book, including the introduction and epilogue, is written by one person. Moreover, it shows: readers will quickly discern the different tones, styles, and discursive registers of each of the writers.”

She adds: “Rather than flatten out or regularise the prose, however, we focused instead on the critical methodology and theoretical concerns that hold the book together. These concerns are...part of the foundation of Anglo-American cultural studies inaugurated in the late 1960s at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. The Birmingham School not only emphasised interpretation as a valid practice, particularly the interpretation of seemingly trivial or mundane social texts, sites and practices, but also promoted and sustained the kind of collective research that resulted in classics like Resistance to Rituals and The Empire Strikes Back.

“In other words, we have very self-consciously identified ourselves in relation to the intellectual tradition of British cultural studies, treating the Las Vegas strip as a system of cultural and social practices and drawing on the insights from multiple scholarly fields. Because it is grounded in interdisciplinary research, Strip Cultures does not map easily onto conventional academic disciplines. For example, anyone looking for a history of tourism in the western US is going to be disappointed. But we believe this method is richer rather than poorer for the way it is broadly defined.”

What did she think of Las Vegas the first time she encountered it? “It was hot, and by the third day I fled to the desert and Hoover Dam just to get away from the sound of the slot machines. I didn’t have the same immediate and visceral dislike of the strip as I had had of Walt Disney World, but I also didn’t exactly get it, probably because I didn’t gamble at all,” Kuenz observes.

“I didn’t go back until 2010, first with my family, including two daughters, 6 and 10 at the time, and then generally alone. The only exception was spending a day and a half with a friend in tow – a trained dealer who had taught me craps back home. Of all these trips, the last one devoted solely to gambling was the most fun. In hindsight, I could have predicted this. In fact, I enjoyed the solo research trips as well, just walking around with my notebook and camera, dutifully going to all the attractions and resorts, watching and eavesdropping and taking notes, just as I had at Disney World.

“At Disney, however, the tightly controlled theming and space tend to reinforce the same conclusion, so that every new ride or park reiterated the same point. Las Vegas has a wide range of people, places and attractions and is just a lot messier, more carnivalesque generally, and I’m not even particularly talking about the booze and girls. The research and writing were similarly more chaotic; it evolved over time. I knew going in I wanted to write about surveillance, urban spaces connected by wi-fi, and how people act in them, but I could not have predicted that this would lead me to the CSI and Bodies exhibits, much less The Gun Store.”

Are these two famed worlds of entertainment, one officially focused on wholesome family fun and the other on adult forms of excess, more alike than would first appear? Kuenz says: “What is most similar about Disney and Vegas, and this is why we chose the latter for the sequel, is that it offers the same occasions to unpack cultural forms and practices that are symptomatic of early 21st-century life.

“One premise of the new book is that, rather than an exception to the rest of the country, the Vegas strip is emblematic of it; not a metaphor, but a model. In fact, a lot of what we write about is not specific to Las Vegas at all. That CSI exhibits like the one at the MGM, or Madame Tussauds, or the ubiquitous Bodies shows, can be found in other places, is the point.

“If anything, focusing on more familiar and widely available tourist sites and social practices helps diverse readers in different places see the connection between Las Vegas and their own daily life, where, for example, the same global system of food production, distribution (and, finally, waste) required for the Vegas buffets also governs their local chain restaurants. Elsewhere, we’ve tried to look at more familiar Vegas themes from different angles: water not just as it figures in environmental history, but as entertainment commodity; sensory experiences other than sex.”

For those who have resisted its lure to date, is Las Vegas worth a visit?

Kuenz affirms: “Anyone interested in contemporary culture, architecture, urban space needs to see Vegas. In its most recent incarnation, it is going for global city status: really high-end leisure consumption, shopping and food especially. The aspiration is Dubai.

“It’s quite different in 2015 from how it looked only 10 years ago, and, for better or worse, although different in scale, Las Vegas is what much of the rest of the country will be like soon enough – indeed already is like, probably more than most of us realise.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: My bag’s packed. When do we go?